Physics Today ads track employment boom and bust

Ernest Lawrence (left), Glenn Seaborg, and J. Robert Oppenheimer tinker in 1946 with a cyclotron, which was being converted from its wartime use as a mass spectrograph. Physicists’ role in the success of the American war effort contributed to postwar funding and job opportunities.

Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

This month marks the 70th anniversary of Physics Today’s first issue in May 1948. As historian David Kaiser writes in his May 2018 feature article

That professional arc for the physics community is played out in the advertisements of Physics Today. In the 1950s and 1960s, Physics Today was filled with ads from companies eager to recruit physicists. By the 1970s, those ads had vanished. Many of the changes brought on by that physics jobs crisis are still with us today, including a reliance on postdoctoral positions.

Physicists in demand

The postwar period saw massive increases in physics PhD enrollment in the US. The expansion of educational funding in the GI Bill and the passage of the National Defense Education Act in 1958 sent more and more students into graduate school in physics. In 1955, 500 physics PhDs were awarded in the US; in 1965, there were 1000; and by 1970, the number had risen to more than 1500. At the University of California, Berkeley, the physics department became too large to hold a departmental picnic anywhere on the university’s grounds.

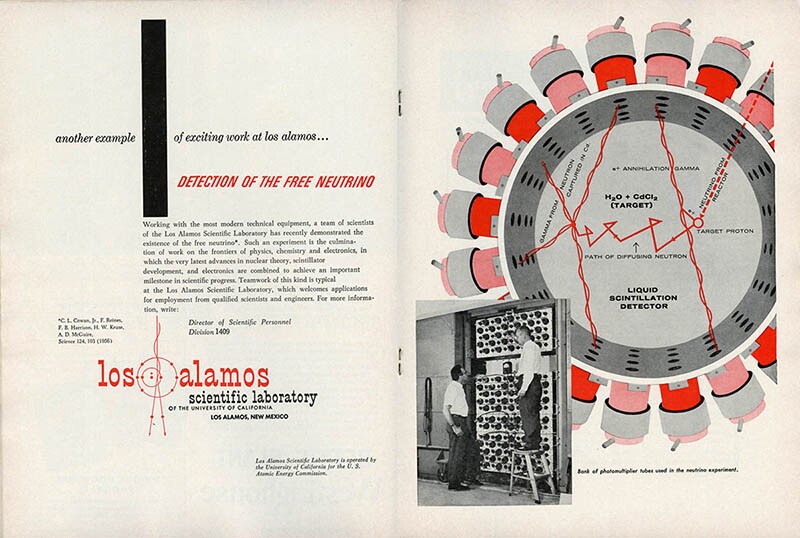

A 1950s ad in Physics Today for jobs at Los Alamos promised physicists the chance to work on cutting-edge science. Click the image to enlarge.

Students chose physics in large part because of the career options that awaited those with degrees. A physics PhD usually led to employment opportunities not only in academia but also at the dozens of private companies and defense contractors who needed physical scientists to work on their projects. Even with rapid postwar expansion in physics programs, demand for physicists outstripped supply. In 1962 the Placement Service at the American Institute of Physics, which publishes Physics Today, listed 514 jobs for physicists but registered only 449 PhDs looking for work.

That demand was reflected on the pages of Physics Today. Many companies and large academic laboratories looking for PhD physicists were not content to place simple black-and-white classified ads in the “Positions Offered” column. Potential employers including Los Alamos National Laboratory, General Dynamics Corporation, and Lockheed Aircraft Corporation purchased large, eye-catching ads to attract applicants. In the January 1958 issue, 44% of the ads outside the classifieds were for jobs. Though some ads requested applications for a specific position, most were far more general; they encouraged readers to write to the personnel office to learn more about all the open positions.

Douglas Aircraft Company tried to lure physicists by emphasizing the lifestyle advantages of a job in California. Click the image to enlarge.

Job ads aimed at PhD physicists, as historian Alex Wellerstein has written

Many of the ads drew on Cold War anxieties about communism and the Soviet Union. An ad for the Sandia Corporation depicted two gunslingers facing off, with the headline “No Second Best.” Sandia told potential employees, “Our business is design and development of nuclear weapons—weapons that stop potential aggressors and defend our freedom. And in this kind of work, either you’re best, or you’re nothing.” The ad went on to assure physicists that Sandia’s home city of Albuquerque, New Mexico, provided “pressure-free, relaxed, pleasant living” and “varied recreational activities.”

Boom and bust

Even as physics PhD enrollments kept expanding, signs of trouble started to appear. As the Cold War entered a period of détente in the late 1960s, some of the funding that had fueled the growth in physics jobs began to vanish. The combination of funding cuts and an economic downturn proved devastating for the job aspirations of PhD physicists. In 1968 the AIP Placement Service recorded just 253 jobs for 989 applicants. In 1969 Physics Today reported that 30% of job seekers with new physics PhDs and 40% of job seekers with new master’s degrees had received zero job offers

That trouble was reflected in the advertisements in Physics Today. By 1965 job ads represented just 25% of the total, a noticeable drop from seven years earlier. By the 1970s, pricey full-page color ads for jobs were gone. Companies went from trying to woo physicists with flashy images to assuming they would have their pick of applicants if they placed a classified ad in “Positions Offered.” The January 1975 issue of Physics Today contained 116 nonclassified ads; only one of them advertised a potential job.

A May 1957 ad in Physics Today for positions at the Sandia Corporation played on Cold War anxieties about nuclear weapons and competition. Click the image to enlarge.

Physics Today’s coverage of the jobs crisis was initially rather unsympathetic to disappointed job seekers. In a June 1969 editorial

Readers—particularly graduate students―quickly responded with a flurry of aggravated letters. “I am aghast that R. Hobart Ellis Jr could take such an irresponsible position,” wrote

Legacy of the crisis

Despite the field’s professional struggles, the 1970s was a decade of exciting physics

One consequence of the crash was the expansion of temporary postdoctoral positions, stopgaps for both cash-strapped departments and physicists eager to find employment. A 1986 AIP survey

The story of the 1970s jobs crisis will likely sound familiar to physicists who lived through the 2008 financial crash and its aftermath. In 2016, 22% of recent physics PhDs reported feeling underemployed