Photovoltaic current shows its split personality

Since the 19th century, scientists have known that illuminating crystals with light can excite electrons through the photovoltaic effect. Photoexcited electrons in a symmetric crystal are equally likely to move left or right; however, they can be coaxed into generating a net current by uneven illumination, as first observed by Edmond Becquerel in 1839, or by crystal inhomogeneities, such as the p–n junctions used in solar cells.

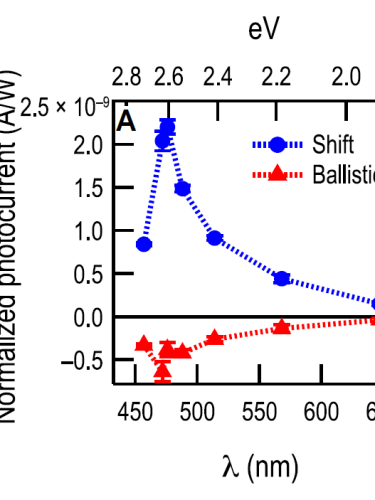

Nearly 50 years ago, Vladimir Fridkin and coworkers reported an unexpectedly large voltage accompanying a photovoltaic current in crystals without a center of symmetry. A theory that was developed 12 years later to explain those experiments predicted that the structure-induced symmetry-breaking should cause two coexisting types of current. One, which they called ballistic, involves a net flow of charge; the crystal asymmetry causes a biased distribution of electron momenta, so excited electrons are more likely to move in a particular direction. The other, a quantum phenomenon they named the shift current, does not involve charge transport. Instead, it results from the displacement of a wavepacket consisting of a photon entangled with an excited electron. However, the femtosecond decay time scale of the shift current is much shorter than that of the ballistic current, and the shift current proved too short-lived to measure.

Jonathan Spanier