Photonic doping tunes transparent media

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.3544

By definition, a material’s refractive index n is the ratio of the speed of an electromagnetic wave in vacuum to its phase velocity in the material. It’s also given by (εμ)1/2, where ε is the material’s electric permittivity and μ the magnetic permeability. So the phase velocity becomes effectively infinite if ε (and thus n) ever approach zero, which can happen when free electrons in materials such as metals and heavily doped semiconductors are driven by the electromagnetic wave to oscillate at their resonance (plasma) frequencies. And for an incident wave of fixed frequency, a huge phase velocity implies a huge wavelength.

In 2006 Mário Silveirinha (now at the University of Lisbon) and the University of Pennsylvania’s Nader Engheta showed theoretically that one can exploit the ultralong wavelength at microwave frequencies to connect two separate waveguides with a long, narrow, two-dimensional channel filled with an ε-near-zero (ENZ) material. 1 As it flows from one waveguide into the channel, the radiation becomes so delocalized that it can efficiently traverse the channel and enter the other waveguide regardless of the channel’s length or curvature. Counterintuitively, the narrower the channel, the greater the wave transmission. Two years later the researchers had designed and built a working device.

Engheta and his collaborators have now shown how to generalize that efficient transmission for an ENZ medium that fills any 2D area. 2 The achievement gives engineers room to better showcase the materials’ advantageous properties. They act as directional filters because only normally incident radiation can penetrate them. By the same token, they are also light shapers because the wavefront of an emerging beam must be parallel to the contours of the interface. The radiation pattern from an ENZ antenna, for instance, can be made sharply directional. The ENZ literature abounds with potential applications: light trapping, nonlinear wavemixing, quantum information processing, and heat management, among others. 3

The dope on dielectrics

The trick to the generalization is modifying an ENZ material’s near-infinite impedance, given by (μ/ε)1/2, so that it matches that of the surrounding finite-impedance material and prevents reflections of the normally incident wave at the entrance and exit ports. Narrow-channel constrictions sidestep the need for such matching at the boundaries. But for an unconstricted interface, impedance matching requires that both ε and μ be near zero, a combination that no natural material can boast at any frequency.

Using a technique they call photonic doping, Engheta and company demonstrate that one can implant an ENZ material with dielectric impurities specifically chosen to tune the material’s effective μ to near zero. 2 Although the impurities are not necessarily magnetic themselves, they can change the magnetic field inside the host in order to alter its optical properties.

Conveniently, because the wavelength of the electromagnetic field is effectively infinite inside the material, the dopants need not be distributed homogeneously. Indeed, as the researchers showed theoretically and experimentally, even a single dielectric particle implanted anywhere in the host can do the job. Choosing the dopant’s appropriate size and ε for a given area of its host boils down to solving a boundary-value problem.

Photonic doping goes beyond impedance matching, though. The ability to tune the effective μ over a large range of values, from negative to positive, makes the technique broadly applicable. As an ENZ body’s effective μ approaches infinity, for instance, it becomes a perfect magnetic shield.

Metamaterial for microwaves

For more than a decade, researchers have used arrays of composite materials whose effective ε and μ are designed to produce electromagnetic properties impossible to find in nature: an ability to refract light in a direction opposite that of ordinary materials, for instance, or to appear invisible at certain frequencies (see Physics Today, February 2007, page 19

What’s more, the effective ε of the composite material remains zero despite the presence of the dopant—no matter its size. That’s because the phase and magnitude of the magnetic field must remain spatially uniform inside an ENZ host, including around the dopant. The upshot, as Engheta puts it: “Because the structure’s effective ε cannot change in response to the changed dielectric properties, its effective μ does, even though neither material is magnetic.”

Another consequence of the field’s spatial uniformity is that the location of the dopant in its ENZ host doesn’t matter. Nor does the host’s external geometry, as long as its cross-sectional area remains constant. The invariance may come in handy in applications that call for bendy metamaterials that change shape.

Engheta and coworkers’ proof-of-concept experiment is outlined in the

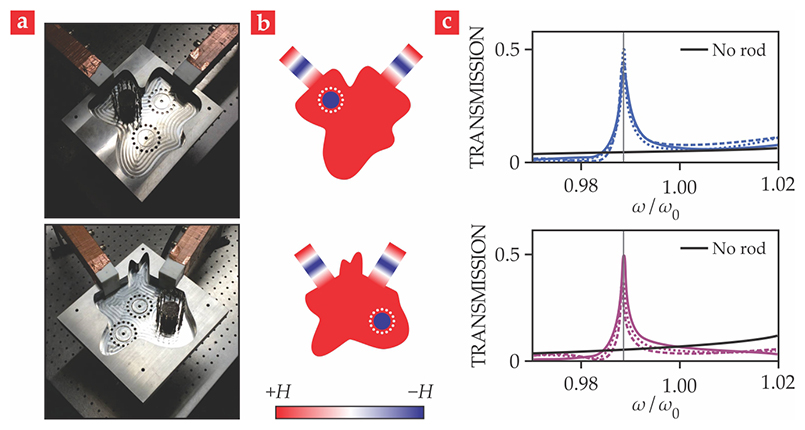

Photonic doping. An impurity introduced into a medium with near-zero permittivity produces a near-zero permeability and resonant transmission. (a) The copper-clad waveguides (brown) are the input and output ports for a metamaterial comprising two parallel metal plates separated by an air-filled cavity doped with a black dielectric rod. Two configurations are shown, with the top plates removed to show the cavities’ different geometries and possible positions of the rod (dashed circles). (b) Snapshots of the simulated microwaves’ magnetic field H reveal its predicted spatial uniformity in the cavities. (c) As the microwave frequency ω nears the cavities’ cutoff frequency ω0, the measured transmission spikes when the rod is in any of the three locations, but is featureless in the absence of the rod. (Adapted from ref.

The

Engheta and colleagues derived the concept of photonic doping specifically for 2D systems, whether natural or artificial. But the concept can be implemented in any 3D body with a high aspect ratio or, as exemplified by the experiment, in any 3D structure whose field variation is fixed in one direction.

References

1. M. Silveirinha, N. Engheta, Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 157403 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.157403

2. I. Liberal et al., Science 355, 1058 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal2672

3. For a review, see I. Liberal, N. Engheta, Nat. Photonics 11, 149 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2017.13