Photonic doping of transparent media

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.7363

By definition, a material’s refractive index n is the ratio of an electromagnetic wave’s speed in a vacuum to its phase velocity in the material. But it’s also given by (εμ)1/2, where ε is the electric permittivity and μ the magnetic permeability. So if ε (and thus n) approaches zero, which can occur when free electrons in materials such as metals and semiconductors are driven by the field to oscillate close to their resonant frequencies, the phase velocity becomes effectively infinite. And for an incident field of fixed frequency, a huge phase velocity implies a huge wavelength. In 2006 Mário Silveirinha and Nader Engheta

Engheta and his colleagues have now developed a technique to generalize that transmission for an ENZ medium that fills any 2D area—no confinement needed. The generalization requires that the impedance of the medium be matched to that of the surrounding media to avoid reflections at the interfaces. The impedance matching, in turn, requires that both ε and μ be zero, a combination that no natural material can boast.

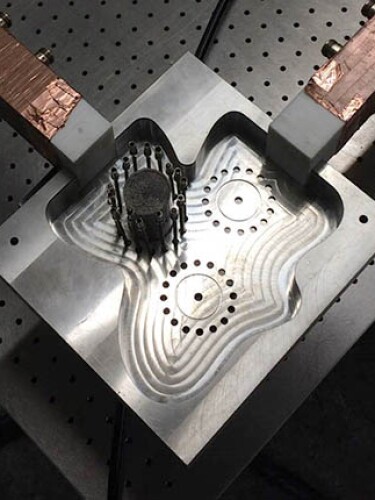

In the new technique, called photonic doping, the researchers create a metamaterial by implanting dielectric impurities whose sizes and permittivities are chosen to tune the effective μ of a bulk ENZ host. Because the wavelength of the electromagnetic field is effectively infinite inside an ENZ material, however, the dopants need not be distributed homogeneously. Indeed, the researchers demonstrated numerically and experimentally that even a single dielectric particle implanted anywhere in the host can do the job. For the same reason, the ENZ host’s external geometry also doesn’t matter, so long as its cross-sectional area remains constant—a feature that may come in handy in applications that call for bendy metamaterials that change shape. In the experiment shown here, light was coupled from one copper-clad waveguide to another through an artificial structure—the air-filled space between two metal plates. Only with the inclusion of the dopant (black) somewhere in the interior did light from one waveguide efficiently couple to the other. (I. Liberal et al., Science 355, 1058, 2017