Organic electronics mimic the sense of touch

When we touch something, the sensation is picked up and relayed to the peripheral nervous system by afferent nerves. That apparently simple process is notoriously difficult to mimic electronically. Artificial touch sensors have been crude, so people with prosthetic hands need to rely on visual clues, and robots have relatively poor fine motor skills. Now an international team led by Tae-Woo Lee

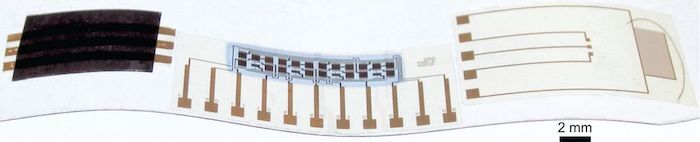

The novel piece of electronics, shown above, has three parts. Flexible organic electronic pressure sensors made of a polythiophene-polyurethane-carbon nanotube composite are arranged in a cluster to mimic the pressure-sensing hot spots on, for example, a fingertip. The 60-mm-wide sensors are then connected to a ring oscillator that serves as the nerve fiber. Pressure on the sensors induces voltage fluctuations between 20 Hz and 100 Hz in the oscillator: the stronger the pressure, the higher the frequency. An ion-gel transistor then takes the signals from multiple ring oscillators and combines and amplifies them into an output current of a few microamperes.

Tests revealed that the artificial afferent nerves signal precisely enough to distinguish among different Braille characters made up of 1.5-mm-high dots. And when the electronic nerve was connected to an actual efferent nerve—one that sends signals to muscles from the spinal cord—in an isolated cockroach leg, pressure on the sensors signaled the leg to move. The current system models only one of four touch-receptor types in human skin. Lee and colleagues plan to replicate the others to bring machines ever closer to developing a human-like touch. (Y. Kim et al., Science 360, 998, 2018