Nuclear and electronic motion in molecules can be computed separately

DOI: 10.1063/1.2930721

The equations that govern molecular structure are well known, but their solutions are not. Exact analytical solutions to the Schrödinger equation don’t exist for systems of more than two interacting particles, and exact numerical solutions are prohibitively time-consuming for systems with more than a few particles. Researchers need to make approximations, and one of the most basic of those is the Born–Oppenheimer approximation. Put one way, it says that the molecular wavefunction can be written as the product of a nuclear wavefunction and an electronic wavefunction, and that the nuclear kinetic-energy operator acting on the electronic wavefunction is negligible. Put another way, it says that when the heavy nuclei move around, the light electrons adjust so quickly that the response might as well be instantaneous.

The Born–Oppenheimer approximation allows computational chemists to split the Schrödinger equation into separate equations for the electronic and nuclear wavefunctions and solve them one at a time. First, they find the electronic energy—usually the ground-state energy—for many different configurations of fixed, or “clamped,” nuclei. (Approximations are still needed; see the article by Martin Head-Gordon and Emilio Artacho, Physics Today, April 2008, page 58

But if the electrons are not in a stationary state—if they’re in the process of relaxing from an excited state or adjusting their charge distribution in response to ionization by a laser—that protocol breaks down: A nonstationary state doesn’t have a definite energy that can be used to create a potential energy surface. Some researchers, including Yngve Öhrn and Erik Deumens of the University of Florida and Todd Martínez of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, have developed ways to model the dynamics of the electrons and nuclei simultaneously, bypassing the Born–Oppenheimer approximation. Now, Lorenz Cederbaum of the University of Heidelberg in Germany has come up with a different approach—a way of treating the time-dependent electronic and nuclear dynamics quantum mechanically and separately. 1

As time goes by

Cederbaum has published prolifically on the problem of calculating the electron dynamics for a fixed nuclear geometry. But it always bothered him that he was ignoring the nuclear motion, so he set out to solve for the nuclear wavefunction too. Öhrn describes the result as “an elegant way of looking at the dynamics of electrons and nuclei in molecules, and very much a continuation of Cederbaum’s work of the past several years.”

In contrast to the time-independent Schrödinger equation, which admits real-valued solutions, the time-dependent Schrödinger equation is inherently complex. As a starting form for the molecular wavefunction, Cederbaum considered a product of a nuclear wavefunction, an electronic wavefunction, and an additional time-dependent phase that he then treated as part of the electronic wavefunction. He collapsed the time-dependent Schrödinger equation onto the space of nuclear coordinates and chose the time-dependent phase in a way that eliminated a particularly cumbersome term. The nuclear Hamiltonian that was left looked exactly like a kinetic-energy term plus a potential-energy term. When he took the electronic wavefunction to be a stationary state, the potential-energy term became equal to the energy of that state—reproducing the standard Born–Oppenheimer approximation exactly.

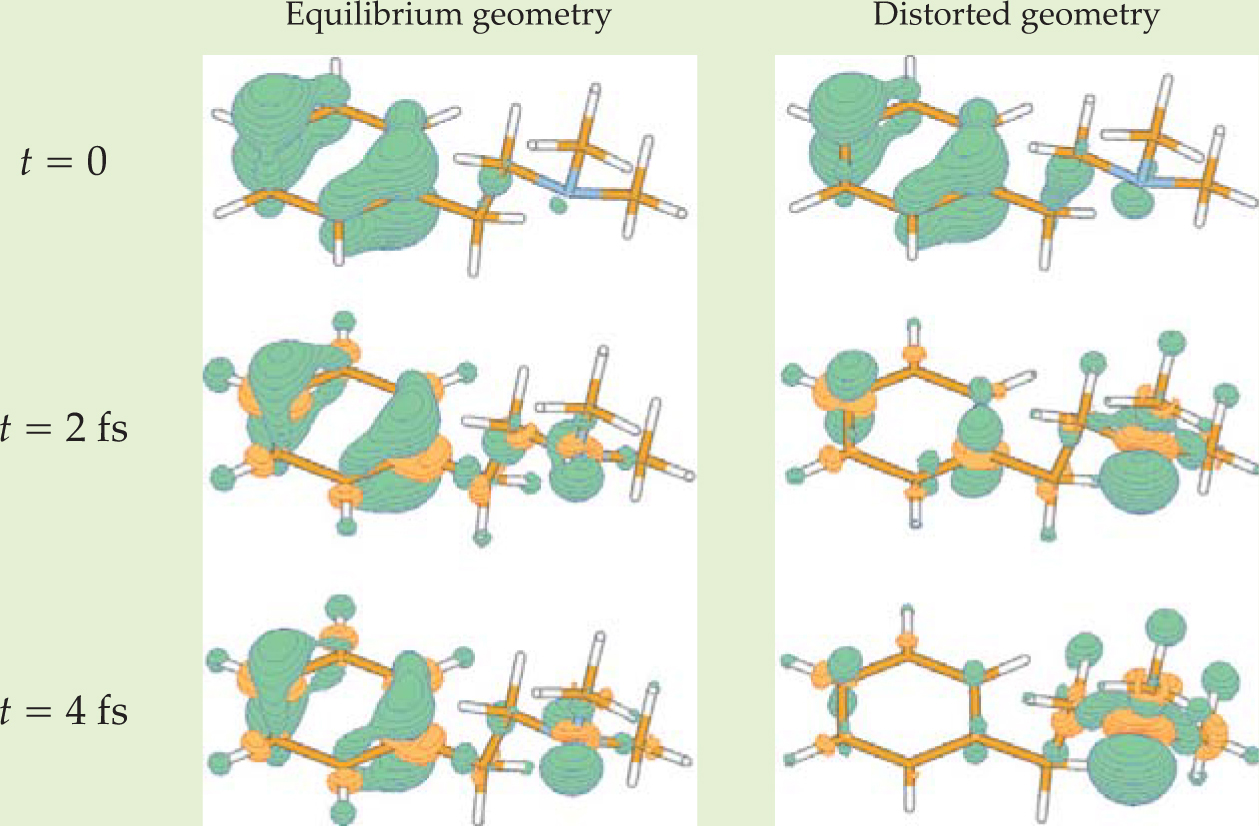

Cederbaum’s effective time-dependent potential-energy function is made up of derivatives of the electronic wavefunction with respect to the nuclear coordinates. In practice those derivatives could be computed by calculating the time-dependent electronic wavefunction for many different configurations of clamped nuclei (see figure 1), creating a function that depends on time, the electronic coordinates, and—parametrically—the nuclear coordinates. Like the standard Born–Oppenheimer approximation, Cederbaum’s method thus allows a potential energy surface for the nuclei to be computed from the clamped-nuclei solution to the electronic problem.

Figure 1. Theoretically calculated electron dynamics following ionization of an organic molecule for two different fixed nuclear geometries. Hole density is shown in green, and surplus electron density is shown in orange. In the equilibrium molecular geometry at left, the hole lingers on the molecule’s benzene ring to a much greater extent than in the distorted geometry at right. From clamped-nuclei calculations such as these, it is possible to extract an effective time-dependent potential energy surface, from which the nuclear dynamics can be predicted.

(Adapted from ref. 2.)

Charge-transfer model

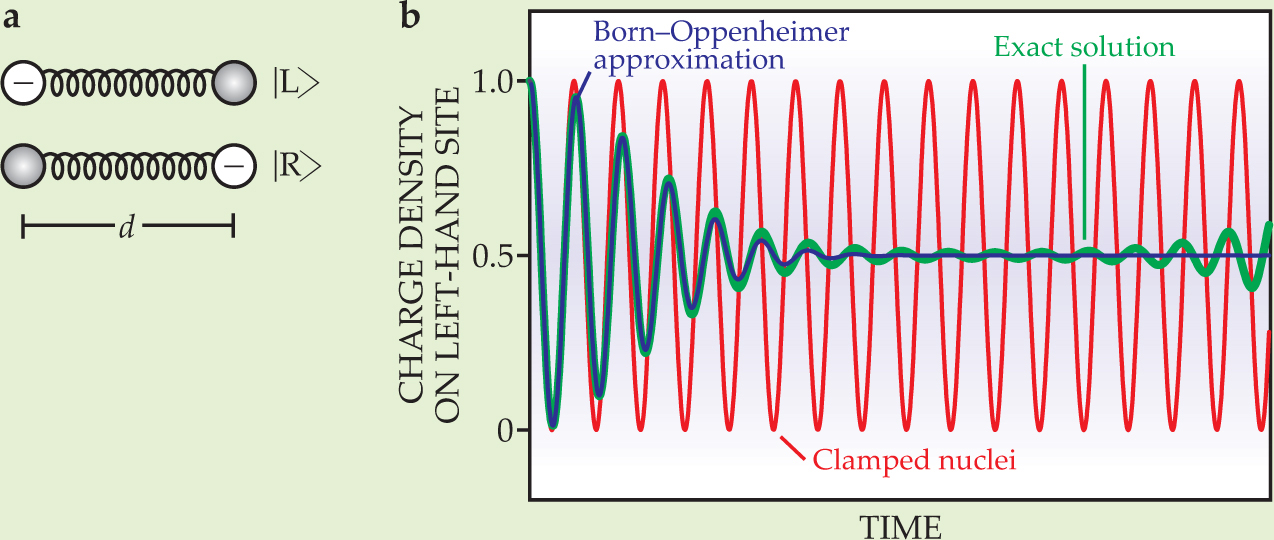

To test his method for a time-dependent system, Cederbaum used a simple charge-transfer model, sketched in figure 2(a), in which the nuclear interaction is represented as a harmonic spring and the electronic motion is modeled as a two-state system. The single electron can be in the left-hand state |L>, the right-hand state |R>, or any superposition of the two. The electronic eigenstates are (|L> + |R>)/

Figure 2. A simple, exactly solvable model system serves as a test for the time-dependent Born–Oppenheimer approximation. (a) A single electron can occupy either of two sites or any superposition of the two. The sites themselves—the nuclei—are connected by a harmonic spring. The electronic eigenstates, the symmetric and antisymmetric superpositions of |L> and |R>, are separated in energy by an amount that depends on the nuclear separation d. (b) The electron starts on the left-hand site and is allowed to propagate. When the nuclear distance is fixed (red curve), the electron oscillates sinusoidally between the two sites. But the time-dependent Born–Oppenheimer approximation (purple curve) predicts a damped oscillation and a charge density that eventually equilibrates. The exact solution (green curve) agrees with the Born–Oppenheimer approximation for short times, but at longer times the oscillation amplitude increases again.

Figure

Validity only over short durations is a general characteristic of Cederbaum’s method. Its range of accuracy can be extended by considering the electronic wavefunction as a superposition of two (or three, four, or even more) orthogonal electronic states, each with its own complex phase, associated nuclear wavepacket, and effective nuclear potential. The resulting equations of motion are coupled—the effective nuclear potential for each wavepacket depends on the electronic dynamics of all the others—but still solvable by the same method. In the charge-transfer model, two orthogonal states span the entire electronic space, so including them both yields the exact solution. In real systems, the number of electronic states is infinite, and including more and more of them would give successively better approximations.

Cederbaum hasn’t yet determined how many states he would need to include for his method to give useful results for a real system. But he points out that it’s not necessary to extend the time horizon to infinity. Many electronic processes of interest last for only a few femtoseconds—after that, a full description of the electronic and nuclear dynamics may no longer be needed.

Attosecond applications

Real systems to which Cederbaum’s method could be applied are likely to be deeply entwined with the emerging field of attosecond physics. With light pulses of ever-decreasing durations and ever-more-precisely controlled shapes, researchers are able to probe and even control molecular systems on the time scale of electronic motion (see Physics Today, April 2003, page 27

References

1. L. S. Cederbaum, J. Chem. Phys. 128, 124101 (2008).https://doi.org/JCPSA6

10.1063/1.2895043 2. S. Lu¨nnemann, A. I. Kuleff, L. S. Cederbaum, Chem. Phys. Lett. 450, 232 (2008).https://doi.org/CHPLBC

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org