Nobel Prize in Chemistry honors the discovery of quasicrystals

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.1349

The annotation that Israeli scientist Dan Shechtman scribbled into his lab notebook on 8 April 1982 was as astounding as it was brief: “10fold???” At the time it was held that only periodic atomic lattices possessed the requisite order to diffract a beam of electrons into a pattern of points, or Bragg peaks. And geometry plainly demands that such lattices have two-, three-, four-, or sixfold rotational symmetry.

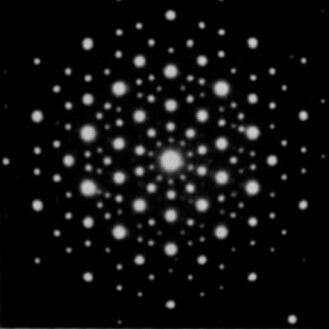

Shechtman’s aluminum–manganese alloy, however, produced the crystallographically forbidden, tenfold-symmetric diffraction pattern

1

shown in figure 1. The material was soon recognized as a quasicrystal, the first in a fundamentally new class of ordered solids. (See PHYSICS TODAY, February 1985, page 17

Figure 1. The electron diffraction pattern generated by Dan Shechtman’s Al6Mn quasicrystal along an axis of fivefold symmetry. (Adapted from ref.

“It was not twinning”

At the time of the milestone discovery, Shechtman was on sabbatical from his professorship at the Technion–Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa and working at the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST) in Gaithersburg, Maryland. A skilled electron microscopist, he had been invited by the bureau’s John Cahn to help study rapidly cooled alloys of aluminum and transition metals.

Months into his stay, the visiting scientist was making transmission electron microscope images of Al–Mn ribbons, which he had prepared by quenching alloy melts on a cool, spinning disk. He happened upon one sample so strongly diffracting that it appeared dark in bright-field images. That sample, a mixture containing six Al atoms for every Mn atom, produced the tenfold-symmetric diffraction pattern.

“I remember counting the diffraction peaks clockwise, one by one up to 10, and thinking that it couldn’t be,” says Shechtman. “So I counted the other way, counterclockwise. Still 10!”

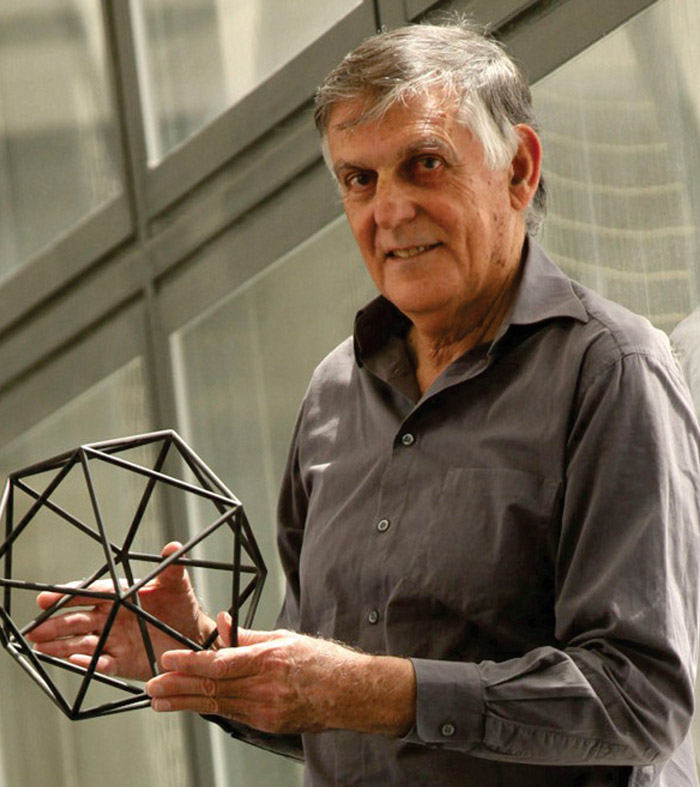

In all, the sample displayed an assortment of symmetries—twofold, threefold, and tenfold—suggestive of an icosahedron, a regular polyhedron having 20 equilateral triangular faces. Icosahedra are actually fivefold symmetric about axes that intersect their vertices, but a diffraction pattern taken along any one of those axes would show tenfold symmetry. (Shechtman is seen holding an icosahedron at left.)

Shechtman

TECHNION—ISRAEL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

Icosahedra, however, cannot be packed to fill space. Therefore, as every crystallography text of the day would have attested, they do not form crystals. The obvious explanation was that what seemed to be icosahedral symmetry was merely an artifact of twinning; 5 or 10 ordinary crystalline grains, arranged like slices of a pie, can disguise themselves as one tenfold-symmetric grain in diffraction images.

To check for twins, Shechtman made electron microscope images showing which area of the Al6Mn sample gave rise to which Bragg peaks. If the diffraction pattern was merely a superposition of patterns produced by twinned grains, each Bragg peak would emanate from a different area of the crystal. Shechtman found the contrary; every peak could be traced to one grain. Further, an electron beam focused onto an area just 20 nm across—too small to harbor multiple twins—reproduced the diffraction pattern in its entirety.

“By the end of that day, I knew that I had something special,” recalls Shechtman. “I did not know what it was, but I knew what it was not. And it was not twinning.”

A new order

Shechtman and Technion colleague Ilan Blech developed a model to explain the result. They hypothesized that Al atoms group around single Mn atoms to form icosahedral shells and that those shells coalign because they are forced to share edges. Although the resulting solid would technically be a glass, not a crystal, it might have enough orientational order to produce diffraction spots resembling Bragg peaks.

The model seemed plausible enough. Simulations had shown that supercooled liquids could host localized icosahedral clusters comprising several hundred atoms. One could imagine that if chilled rapidly enough, a network of icosahedra might emerge and then freeze into place.

Unbeknownst to Shechtman and Blech, the development of another, more ambitious theory had already been under way for years. It sprang from the study of tilings, arrangements of two-dimensional shapes that fill a plane and leave no gaps.

Conventional tilings, like conventional crystals, can be reduced to a single motif that repeats ad infinitum. A grid of uniform squares is an example. But in the 1970s, Oxford University mathematician Roger Penrose began concocting rather unconventional tilings. He showed that with just two shapes—two kinds of rhombi, for example—and appropriate matching rules, one could assemble a tiling that never repeats. Casual inspection of such a Penrose tiling reveals hints of local symmetry—five-pronged stars are a recurring motif in the rhombic tiling—but no regular pattern.

Later, British crystallographer Alan Mackay drew a link between Penrose tilings and condensed matter. In 1982, before Shechtman’s work was published, Mackay imagined a 2D solid, with each atom centered on a vertex of a Penrose tiling. Duplicating the pattern on an optical mask, he used optical diffraction to show that his hypothetical solid would generate a tenfold-symmetric pattern of diffraction spots. 2

Several theorists, including Mackay, began working independently to devise 3D analogues of Penrose tilings, made up of rhombohedra instead of rhombi. Peter Kramer and Reinhardt Neri at Tübingen University in Germany showed that such tilings could be interpreted as a projection of a hypercubic 6D lattice onto 3D space.

Extending 2D formulations proposed by recreational mathematician Robert Ammann, Paul Steinhardt and Dov Levine (University of Pennsylvania) showed that a 3D Penrose tiling has strict, if unconventional, order: The interval spacing of its underlying lattice is prescribed by the Fibonacci sequence. Moreover, they found that the Penrose tiling was just one in an extensive family of quasiperiodic arrangements that, if adopted by atoms, would generate crystallographically forbidden Bragg-peak diffraction patterns.

Aha!

In 1984 Shechtman and Blech were still unaware of the developing theory of Penrose tiling. Meanwhile, their manuscript—a lengthy treatise on all of the various Al–Mn phases Shechtman had observed—had been rejected by the Journal of Applied Physics as unlikely to appeal to physicists. Cahn and French mathematician Denis Gratias helped the authors recast the work into a terse three-page manuscript devoted exclusively to the discovery of the icosahedral phase. The rewrite was quickly accepted by Physical Review Letters.

By the time news of the icosahedral phase began to circulate, theorists familiar with Penrose tilings had already been awaiting its discovery. A prescient Mackay wrote in 1981 that Penrose tilings were “an example of a pattern that might well be encountered but might go unrecognized if unexpected.” 3 Steinhardt, too, was convinced that an icosahedral phase might exist. He says of first seeing Shechtman’s preprint, “When I got to the page with the diffraction pattern, I nearly jumped out of my seat.” The pattern was a near-perfect match to one that he and Levine had computed for a 3D Penrose tiling.

Shechtman and colleagues’ paper detailing the discovery of the icosahedral phase was published in Physical Review Letters on 12 November 1984. Six weeks later, on Christmas Eve, Steinhardt and Levine’s work on quasiperiodicity appeared in the same journal. 4 The theorists dubbed the new form of matter quasiperiodic crystals, or quasicrystals for short.

Critical review

“There is no such thing as quasicrystals,” Nobel laureate Linus Pauling often said of the putative icosahedral phase. “Just quasiscientists.” In fact, most crystallographers shared his suspicion of quasicrystallinity. Conventional crystals fit an intuitive thermodynamic paradigm: There always exists some energy-minimizing microscopic arrangement of atoms, and repetition of the arrangement minimizes energy on macroscopic scales. That atoms would adopt long-range order by any other means seemed physically impractical.

To be fair, Shechtman’s diffraction patterns left room for doubt. The crystals were too small to be analyzed by x-ray diffraction, the preferred and more precise technique. And formed as they were by rapid cooling, they housed imperfections that blurred the Bragg peaks.

It was possible, then, that what seemed to be a quasicrystal was really a locally oriented glass of the sort proposed by Shechtman and Blech. Or the diffraction patterns could have been created by a regular crystal with a large unit cell. Though the unit cell itself might be, say, cubic, the jumble of atoms inside each one might exhibit near-icosahedral symmetry. Pauling himself identified such an approximant, a crystal having a reasonably large unit cell comprising a thousand or so atoms.

A turning point was the 1987 discovery by An-Pang Tsai (Tohoku University, Japan) and colleagues of a thermodynamically stable icosahedral phase, Al65Cu20Fe15. Shechtman’s quasicrystals were metastable and could only be made by rapid cooling. Chilled slowly, they formed ordinary periodic crystals. Tsai’s quasicrystals, and other stable quasicrystals discovered soon thereafter, could be grown by conventional methods into large and nearly perfect grains.

The ensuing high-resolution diffraction measurements eliminated every competing theory except that of quasiperiodicity. For approximants to masquerade as such perfect quasicrystals, demonstrated Steinhardt, Paul Heiney, and colleagues, each unit cell would have to comprise not thousands but hundreds of thousands of atoms. All but the most strident skeptics conceded quasicrystals’ place in the crystallographic lexicon. In 1992 the International Union of Crystallography revised the definition of a crystal to mean “any solid having an essentially discrete diffraction diagram”—which includes quasicrystals.

Legacy

Since the publication of Shechtman’s landmark paper, the number of known quasicrystals has grown into the hundreds and includes at least one naturally occurring quasicrystal, Al63Cu24Fe13, recovered from the Koryak region of eastern Russia. (See PHYSICS TODAY, August 2009, page 14

Thanks to x-ray diffraction and sophisticated computational analysis strategies, quasicrystal structures can now be determined with a precision rivaling that of conventional crystals. (See PHYSICS TODAY, March 2007, page 23

Figure 2. A new order. (a) In a variation of Penrose tiling, neighboring decagonal tiles are allowed to overlap in one of two ways. Maximization of the tiling density then yields a perfect quasiperiodic tiling. (b) Superimposed on a scanning electron microscope image of an Al72Ni20Co8 quasicrystal, the tiling maps to the underlying atomic lattice. Atoms appear as white circles. (Adapted from ref.

Quasicrystal alloys display a rare combination of material properties. Though brittle, they are harder than steel—a trait that makes them useful additives in razor blades and precision medical tools. They have low surface friction, which won them brief popularity as nonstick coatings on frying pans. And they are good insulators, which makes them promising as coatings for turbines. Quasiperiodic structures assembled from colloidal and granular building blocks may function as high-symmetry photonic and phononic waveguides.

As Patricia Thiel of Iowa State University puts it, however, the greatest legacy of Shechtman’s discovery may be that it “touched off a revolution in how we understand solid matter.” Adds Iowa State’s Alan Goldman, “It also taught us to keep our eyes open.”

Dan Shechtman was born 24 January 1941 in Tel Aviv. After serving in the Israeli army, he enrolled at the Technion, where he received a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering and master’s and doctoral degrees in materials engineering. He did postdoctoral research at Wright–Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio before joining the faculty at the Technion, where he remains today. He is also a professor at Iowa State and a senior scientist at the US Department of Energy’s Ames Laboratory.

References

1. D. Shechtman et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 1951 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.1951

2. A. L. Mackay, Physica A 114, 609 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4371(82)90359-4

3. A. L. Mackay, Sov. Phys. Crystallogr. 26, 517 (1981).

4. D. Levine, P. J. Steinhardt, Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 2477 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.2477

5. P. J. Steinhardt et al., Nature 396, 55 (1998).https://doi.org/10.1038/23902