NMR protein structures: No deuteration required

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.7296

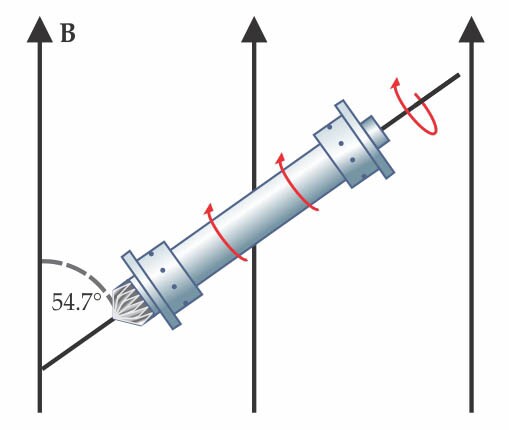

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy is widely used to get structural information about molecules: When placed in a magnetic field, a molecule’s magnetic nuclei precess at frequencies that depend on their chemical environment. Conventional solution-phase NMR—usually based on hydrogen-1 because it has the largest gyromagnetic ratio and highest natural abundance—relies on molecules’ rapid tumbling to average out anisotropic contributions to the signal. But that averaging breaks down for solid samples and large proteins. Researchers can recover the benefits of rapid tumbling by spinning the sample about an axis at a particular “magic” angle with respect to the field B, as shown in the figure. (For more on magic-angle spinning and the other intricacies of solid-state NMR, see the article by Clare Grey and Robert Tycko, Physics Today, September 2009, page 44

Solid-state NMR complements other techniques for finding protein structures. Unlike x-ray crystallography, it doesn’t require a crystalline sample, and it’s well suited to the small and medium-sized membrane proteins currently beyond the reach of cryoelectron microscopy. Even with magic-angle spinning, 1H NMR protein spectra often have many overlapping, unresolvable peaks that make them too complicated to interpret. The spectra can be simplified by replacing some of the hydrogen atoms with deuterium atoms, which are invisible to 1H NMR. But partially deuterating a protein is difficult, expensive, and for many proteins not even possible.

Now Guido Pintacuda

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org