NMR experiments uncover the nuclear Barnett effect

In 1908 Samuel Richardson proposed that changing the magnetization of a ferromagnet could cause it to rotate. If a magnetic field changed the object’s magnetization without applying an external torque, he reasoned, then that change in electron momentum should be transferred to the object’s angular momentum. The following year Samuel Barnett posited that the converse should also hold: Rotating a ferromagnet should change its magnetization. Barnett published the experimental realization of his effect in October 1915, just a few months after Albert Einstein and Wander Johannes de Haas had confirmed Richardson’s prediction. Those experiments provided the first measurements of the electron’s gyromagnetic ratio and established a fundamental connection between mechanical angular momentum and magnetization.

In principle, a Barnett effect should also exist for protons in a bulk sample. But the proton’s magnetic moment is nearly three orders of magnitude smaller than the electron’s. That renders its magnetization due to rotation incredibly small and easily masked by experimental noise. Despite that challenge, Mohsen Arabgol and Tycho Sleator

Tycho Sleator

One reason the search for the nuclear Barnett effect took so long is that the effect lacks obvious practical applications. In fact, it was an application that set Sleator on the trail. He, along with David Grier

Sleator already had a history with NMR. At the University of California, Berkeley, he was a graduate student of Erwin Hahn, an early NMR pioneer who discovered spin echo, a pulsing technique that is integral to NMR spectroscopy and MRI diagnostics. In his final publication

The 2006 paper reported the detection of proton polarization by means of a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID), a magnetometer that can measure extremely small magnetic fields. Hahn realized that the same technique might also be able to detect the nuclear Barnett effect. “He was fascinated by the possibility to measure it,” says Dimitrios Sakellariou of KU Leuven in Belgium, who was then a postdoc at Berkeley. Hahn and other scientists and students spent countless hours designing SQUID experiments and performing computer simulations in the quest to observe the expected effect.

Because they were trying to develop a new MRI technique, Sleator and Arabgol used an NMR method instead of a SQUID to measure the proton polarization. A schematic of their experimental setup is shown. At first glance it seems straightforward. A sample of water spinning at a rate ω is placed in a static magnetic field B0. The protons in the sample are magnetized for two reasons: the magnetic field and the Barnett effect. If B0 stays the same and ω is changed, then any measured change is due to the Barnett magnetization.

But the details of the experiment weren’t so simple. The researchers had to tune many parameters—including the magnetic field, spinner size, and rotational frequency—to find the experimental sweet spot. “Only a narrow combination of these parameters works,” Arabgol says. “And finding this combination requires a lot of systematic tests and measurements.”

Another important choice was using a liquid water sample. Liquids have longer spin–spin relaxation times (T2) than solids, which means their transverse magnetization—the quantity measured by NMR—decays more slowly. They also have shorter spin–lattice relaxation times (T1), so they take less time to equilibrate after a measurement. By maximizing T2 and minimizing T1, the researchers increased their data collection and reduced their statistical noise. Doping the water with copper sulfate further adjusted the relaxation times.

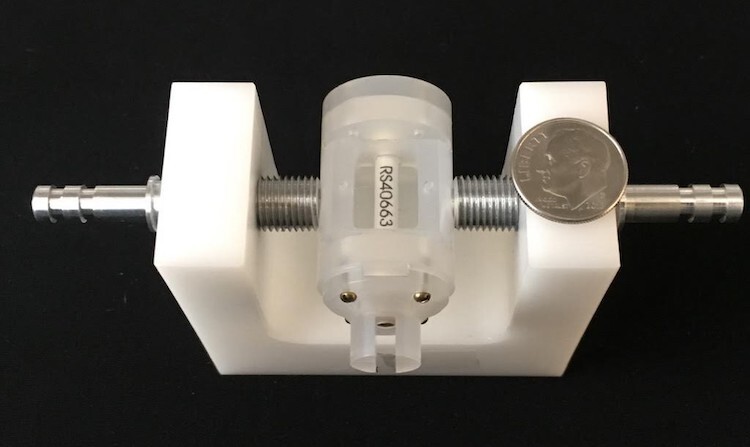

The researchers also had to customize their apparatus to home in on their target measurement. Whereas most NMR experiments target the frequency of the resonance, Sleator and Arabgol needed to know its intensity. Some experimental parameters, such as the sample’s rotational speed, can change the intensity dramatically. The nonstandard setup also ran into other problems. For example, the RF coil, which had more turns than usual so that it would work at low frequencies, wouldn’t fit in the spinner (shown in the photo).

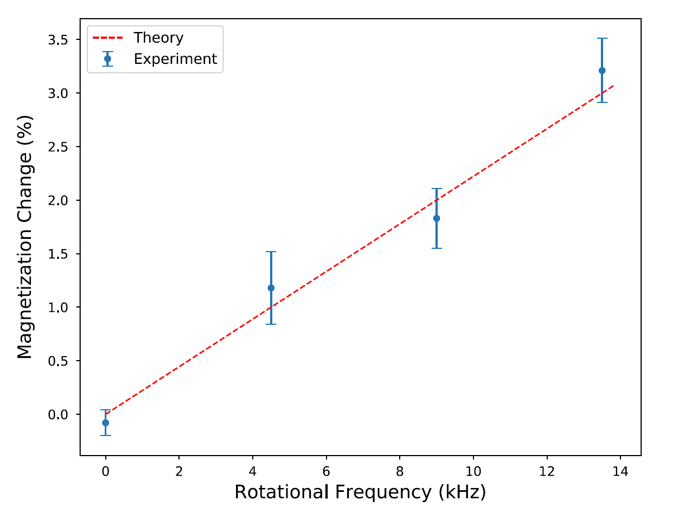

Sleator and Arabgol’s experimental results, shown in the graph above, constitute the first observation of the nuclear Barnett effect. The measurements show that the change in proton magnetization increases with faster rotation, as predicted. The experiment also emphasized another point that is sometimes misunderstood: Rotation does not generate a magnetic field inside the sample. Although the magnetization can be described by an effective magnetic field, that field does not actually exist. If rotation did create a magnetic field inside the sample, that would cause a shift in the observed NMR spectrum; however, the researchers saw no shift at any of the observed spin rates.

Measuring the nuclear Barnett effect in a solid would be the next logical step toward fully understanding the underlying theory. However, according to Arabgol, that experiment is even less straightforward. Solids have less convenient relaxation times, which makes finding a range of experimental parameters that might produce a measurable result nearly impossible—which it may be. Only after the fundamentals are better understood can researchers pursue practical applications.