NIF Moves Forward Amid Controversy

DOI: 10.1063/1.1349602

In early October, just after a House and Senate conference committee recommended $199 million in funding for the National Ignition Facility (NIF) as part of the 2001 budget, Senator Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) rose on the Senate floor and attacked the project.

For the past few years, the $3.5 billion facility under construction at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) has been severely criticized by politicians, government officials, review panels, and some scientists for cost overruns, inefficient management, and unproven science. Even though the lab had made changes in response to the critics, Harkin wasn’t happy with what he viewed as undeserved funding for “a program that is out of control.” In a few simple sentences, the Democrat summed up for his Senate colleagues the key issues surrounding one of the biggest and most controversial projects in science.

“We don’t know if the optics will work,” Harkin said. “We don’t know how to design the [laser] target. Even if the technical problems are solved, we don’t know if the National Ignition Facility will achieve ignition. We don’t even know if this facility is needed.”

At about the same time Harkin was speaking, the NIF Laser System Task Force, which had recommended an overhaul of NIF management a year earlier, was putting together its final report. To the relief of Lawrence Livermore scientists and officials of the Department of Energy (DOE) Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP), the findings were favorable.

No technical obstacles

The task force reported that it had “uncovered no technical or managerial obstacles that would, in principle, prevent the completion of the NIF laser system.” The committee, headed by John McTague, a former vice president of the Ford Motor Co, also concluded that NIF is, “at its core, a research and development project,” a designation that is a point of contention for some critics.

In acknowledging the project’s troubled past, the task force said the “largest remaining issue” for NIF managers “is the restoration of public trust and confidence in the ultimate and successful completion of the NIF project.”

The trust issue is important to the project’s future because cost overruns of more than $1 billion and slippage of several years in the completion date were apparently concealed from DOE officials by LLNL managers. In September 1999, not long after assuring Congress that NIF was on time and on budget, DOE Secretary Bill Richardson learned that he’d been misled by the project’s managers.

“I am deeply disturbed to learn of projected cost overruns and scheduling delays associated with [NIF],” Richardson said a few days after being told of NIF’s troubled state. “I am also gravely disappointed with the University of California and the … Lawrence Livermore Laboratory for its late reporting of these significant problems.” All of this occurred a few days after Michael Campbell, the associate director of lasers at the lab and director of the NIF project, resigned.

Richardson, after telling Congress that “bad management has overtaken good science,” announced a program to straighten out the mess surrounding NIF; officials at LLNL say they have put measures in place to get NIF on track. “It is a whole new world order here,” said Susan Houghton, head of media relations for the lab. “We’ve created a brand new directorate just for NIF, which was not in place a year ago.” Physicist George Miller is the new associate director for NIF programs, and engineer Edward Moses is the NIF project manager.

Critics remain skeptical

But many critics, including scientists, remain skeptical. Stephen Bodner, a physicist who was the director of laser fusion research at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC, for 24 years, sees many scientific problems with the project, but believes NIF’s troubled history comes from the culture of the lab.

That culture is “overselling, making promises, and hoping that somehow you’ll fix things afterwards,” Bodner said. “They know how bright and clever they are, and they’ll sell things and try to get the job done. That’s what we call entrepreneurship and I think they went too far.” Indeed, a blistering Government Accounting Office report on NIF in August 2000 noted that NIF managers “were overconfident about their own abilities to solve project problems.” Another word for what happened is “hubris,” Bodner said.

Until NIF shows some scientific success when its first bundle of eight lasers goes on line in 2004, bringing critics into the fold may be difficult. The project is pushing hard against the edge of laser technology—an edge that some researchers believe is, for the moment, beyond the reach of science. Both proponents and opponents note that NIF, as designed, will be about 50 times more powerful than any previous laser.

“This is a very large project and it has a very large budget, and those two things make it a target for continual evaluation and reevaluation, and that not only means by our critics, but within the project itself,” said Jim Anderson, who heads the NIF project in DOE’s defense programs division.

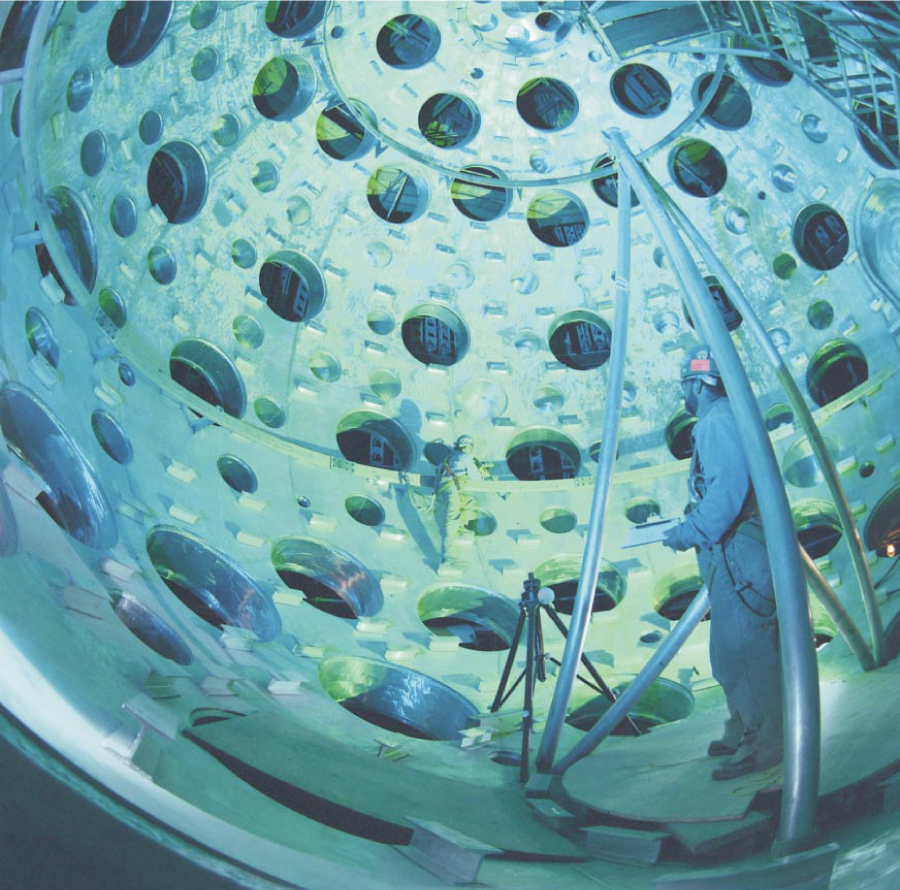

If NIF delivers what it promises after completion in about 2008, the stadium-sized facility will contain 192 lasers capable of focusing 1.8 mega-joules of energy on a deuterium–tritium fuel capsule about 2 millimeters in diameter. A phased 20-ns pulse from the lasers will compress and ignite the nuclear fuel in the capsule through inertial confinement fusion, releasing more energy than was added and simulating the conditions within a thermonuclear weapon.

The simulation is at the core of NIF’s mission: Its primary purpose is to serve as the machine that will allow scientists to monitor the condition of aging US nuclear warheads—the oldest of which were built in the 1970s. By simulating the effects of deterioration on aging warheads, NIF is intended to tell scientists if and when a bomb might no longer function. In essence, then, NIF is a replacement for the underground testing of nuclear weapons that ended in 1992.

NIF is under the control of the National Nuclear Security Administration, the semiautonomous agency within DOE charged with, among other things, overseeing the nuclear weapons Stockpile Stewardship Program. SSP, which primarily involves LLNL, Los Alamos, and Sandia national laboratories, costs about $5 billion per year; its mission is to ensure that the weapons in the nuclear stockpile are safe, reliable, and effective. (See Physics Today, December 2000, page 44

Burton Richter, the emeritus director of SLAC, was on the latest review committee and supports NIF. “I would expect that if [NIF] is typical of projects of this kind, when they are finished and all 192 lasers are in, they’ll be able to run initially at about a third of the full design energy output and it will take them a couple or three years to work it up to full performance,” Richter said.

Sidney Drell, a professor and deputy director of SLAC and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution says he supports NIF as a science project, as a needed element of the SSP, and as a way to attract bright young scientists into weapons research programs. “I think that the scientific role of NIF in terms of the confidence and excellence of the scientific community at Livermore and in the weapons program is significant,” Drell said.

Physicist Thomas Cochran, the senior scientist and director of the nuclear program at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), is one of the most persistent critics of NIF, attacking both the science and the process of the project. Several years ago, Cochran’s group sued DOE over the makeup of an NSF panel being set up to review NIF. Cochran contended that the panel was stacked with people who had economic ties to LLNL; a court put limits on the use of the panel’s work, although NIF scientists say the restrictions had nothing to do with claims of economic conflicts of interest of panel members.

Scientific aims debated

Cochran said he is “disappointed but not surprised” by the final Laser System Task Force report supporting NIF. Among his many problems with NIF, Cochran doesn’t believe the laser will be able to achieve ignition. “It is not going to do thermonuclear ignition in the lab,” he said. “It won’t do what it was sold to Congress to do.”

Cochran, Bodner, and others point to several areas where NIF is likely to fail: inadequate power supplies; the inability to properly propagate 20-ns laser pulses through spatial filters; and damage to the final optics during firing. There are no obvious solutions to these scientific challenges, they say, adding that the commitment to build NIF without a solid scientific basis is foolish. Cochran said that in a recent teleconference to discuss NIF, Richter said “the DOE and the lab have established milestones for the project, but watered down the criteria for NIF. They’ve redefined the criteria as goals. And now they are claiming it is all research and development.”

Richter doesn’t believe the criteria have been diluted and said Cochran “misinterpreted” his comments.

LLNL’s Moses strongly denied Cochran’s charge. “I know that the NRDC and other organizations have recently taken the tack that NIF and the DOE have in some way relaxed the criteria for project completion or for performance. That is absolutely not true. There have been no criteria loosened in any way.”

Moses said that while it is important for members of the “user community” to be skeptical of any big science project, they should be aware that “there were six major technology areas that had to be resolved … and essentially they are all done.” A year ago, critics were saying the 3000 or so pieces of optical laser glass “could not be brought to full manufacturing capability,” Moses said. “We now have approximately 30% of the glass we need for NIF already in hand.”

A potentially critical problem with the project—building the massive laser with a design that did not take clean room construction methods into account—“was of great concern to me,” Moses said. LLNL scientists raised the issue in the first place, he said, and “we have now worked through the methodology for clean construction. We have consulted with and hired people that come out of the semiconductor and pharmaceutical industries to do this [develop clean room standards].”

Despite Harkin’s concerns, Congress grudgingly approved the $199 million for NIF in fiscal 2001, but with several conditions. Only $130 million goes to the project immediately; the remaining $69 million will be withheld until the end of March. At that time, Moses and DOE officials must have completed new project and budget plans, a certification of construction progress, and a study on whether the full 192-laser facility is needed.

That last point raises a separate set of questions about the need for NIF in the stewardship program. Some critics, such as Frank von Hippel of Princeton University’s Center for Energy and Environmental Studies, believe the nuclear stockpile can be safely maintained without NIF. And the questions about the need for NIF in the first place lead to another question about the ultimate goal of NIF—ignition of the target.

Even if NIF planners overcome the many technical problems, an open scientific question exists about whether all 192 lasers working properly will actually achieve ignition. If ignition can’t be achieved, will NIF still be scientifically valuable?

“We are still confident we can achieve ignition, and that is still our goal for NIF,” LLNL’s Houghton said. “That doesn’t mean, however, that there aren’t some experiments that can’t be done, or some elements of the SSP that can’t be managed without achieving ignition.”

Drell agreed that achieving ignition isn’t necessarily the final measure for NIF. “I want ignition,” Drell said. “But to say that a failure to achieve ignition is a failure of the stewardship program, I reject. It’s a failure to do things one wants to do, but I don’t want to have that coupled with saying we can’t do stewardship unless we achieve ignition.”

For NIF itself, even apart from stewardship, a lack of ignition wouldn’t mean failure, Drell said. “As in all projects, you’re going to improve and learn something and I’m willing to believe that what we’ll learn will be an important step. You look at high-energy physics, and you find out that machines, when you build them, you have to work and tune them up and eventually you find out how to get beyond even what your original goal was. I think that is good science.”

Bodner doesn’t have that much faith in NIF. “The whole thing, from one end to the other, has problems,” he said. “With the end of underground testing, the nuclear weapons program needs cautious, conservative scientists, not optimistic entrepreneurs. It needs stockpile curatorship, not stockpile stewardship. NIF was designed to maintain science at the center of the nuclear weapons program, and I think there is a time when scientists ought to say they shouldn’t be at the center.”

LLNL workers stand inside the 10-meter-diameter target chamber that is the heart of NIF. Lasers entering the chamber will be symmetrically distributed to trigger ignition in a 2-millimeter deuterium–tritium fuel capsule.

LLNL

More about the authors

Jim Dawson, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US .