New technique probes structural elements of folded chromosomes

DOI: 10.1063/1.3273004

Stretched to its full length, a human chromosome would be several centimeters long. It is packed, along with its 45 companions, into a cell nucleus just a few microns across in such a way that all the necessary genes are readily accessible to RNA transcription. Figuring out how that packing is done has been a puzzle.

By staining certain chromosomes or genes and looking at them under a microscope, researchers have gained some insight. They’ve found that chromosomes tend not to be tangled together; rather, each one stakes out its own territory. And there are patterns in the arrangement of those territories: Certain pairs of chromosomes tend to prefer to be near each other. But microscopy offers far from a complete picture. The structures of the individual chromosomes are just too small and too complicated.

Now a research team led by Eric Lander of MIT and Job Dekker of the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester has developed a method, called Hi-C, for examining chromosomes’ folded conformations. 1 Dekker’s postdoc Nynke van Berkum tackled the biochemical technique, and Lander’s student Erez Lieberman-Aiden took care of the mathematical analysis. Together, they’ve found that chromosomes behave very differently from tangled polymers in equilibrium.

A parallel process

Hi-C is an extension of an earlier technique—called chromosome conformation capture, or 3C—that Dekker helped to develop while he was a postdoc with Nancy Kleckner at Harvard University. 2 In 3C, researchers use formaldehyde to chemically link parts of a chromosome that are close in space. Then, with an enzyme, they cut away the DNA on either side of the cross-link. By sequencing the linked segments of DNA and comparing the sequences with known genome data, they learn which parts of which chromosome they linked.

But 3C could only detect contacts a few at a time—for a folded chromosome with tens or hundreds of millions of base pairs, the method offers only a very coarse view. Hi-C, on the other hand, allows the observation of many more contacts in a short time. Two advances were necessary for that development. The first was the vast improvement in parallel DNA sequencing that has taken place in the past two years. The second was finding a way to isolate and purify so many DNA strands of interest.

The researchers verified that their new method could confirm the results that were already known from microscopy. Fortunately, it could. Hi-C found many fewer contacts between different chromosomes than within the same chromosome, as expected of chromosomes that aren’t intertwined. And there were more interchromosomal contacts between pairs that microscopy indicates tend to cluster together.

Pretty in plaid

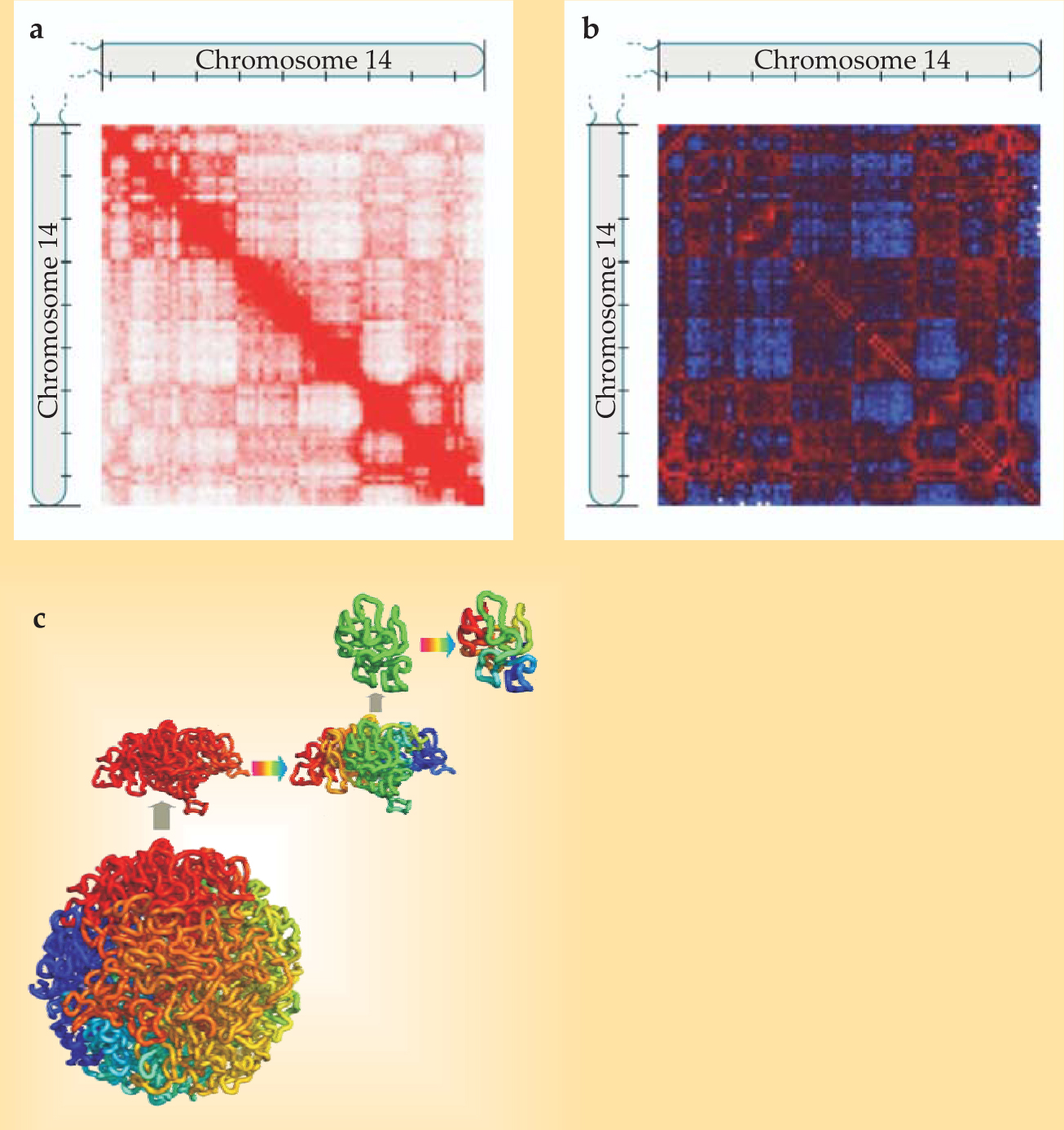

Plotting a matrix of contacts within a chromosome yields a plaid pattern, as shown in panel a in the figure. Not surprisingly, points that are near each other on the stretched-out chromosome are more likely to be in contact in the folded structure than are points at opposite ends of the chromosome. Still, the off-diagonal regions of the matrix aren’t a uniform pale pink: Some pairs of points are more likely to be in contact than one might expect given their linear distance along the chromosome. To sharpen those features, the researchers created a contact matrix normalized for that linear distance (shown in panel b) and a correlation matrix of points that share many common neighbors. From those, they found that two segments that were both far from a third segment tended to be close to each other—that is, the chromosome was segregated into two so-called compartments. Especially interesting was that most of the DNA that was known to be active in that particular cell type fell into one compartment, and most of the inactive DNA into the other.

Zooming in further, the researchers examined the structure of chromosome segments a few million base pairs long. They had no reason to expect chromosomes on that scale to behave much differently from any other tangled polymer. But the Hi-C data told them otherwise: The relationship between contact frequency of points and their distance along the chromosome was different from what widely used polymer models would predict.

Delving into the literature, they found a two-decade-old paper proposing that chromosome segments might form structures called fractal globules. 3 An example is shown in panel c of the figure. The colors represent contiguous segments of the stretched-out chromosome; they also form separate, compact regions in the globule. Each of those regions is structured the same way, as is each of the region’s regions, and so on.

The fractal globule fits the Hi-C data better than any other structure the researchers considered—although they can’t rule out the possibility that a different structure they haven’t considered works just as well. But if the fractal globule structure is correct, it hints at a solution to how the folded chromosomes can be so compact and yet so accessible, since unraveling part of a fractal globule does not cause much disruption to the rest.

To your health

So far, Hi-C has been applied only to cultured cell lines. Those are human cells, but they’re far removed from healthy cells in a human body. One of the lines was derived from cancer cells, and another has been modified by a virus. The researchers would like to apply the method to healthy cells to see, for instance, whether there’s a difference in chromosome structure in different types of tissue. It’s difficult, though, to obtain from healthy tissue the 10 million to 20 million cells necessary for a Hi-C analysis.

(a) Hi-C contact matrix for one human chromosome. Observed contacts are shown in red. Tick marks on the axes indicate segments of 10 million base pairs. (b) The same matrix normalized for distance along the chromosome: Red represents more than the average number of contacts between points of that genomic distance, and blue represents fewer. The plaid pattern indicates that two segments both having few contacts with a third segment tend to have many contacts with each other. (c) The fractal globule, a likely folding structure for chromosome segments a few million base pairs long.

(Adapted from ref. 1.)

References

1. E. Lieberman-Aiden et al., Science 326, 289 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1181369

2. J. Dekker et al., Science 295, 1306 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1067799

3. A. Y. Grosberg, S. K. Nechaev, and E. I. Shakhnovich, J. Phys. (France) 49, 2095 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1051/jphys:0198800490120209500

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org