Nanobubbles distinguish themselves from impostors

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.2773

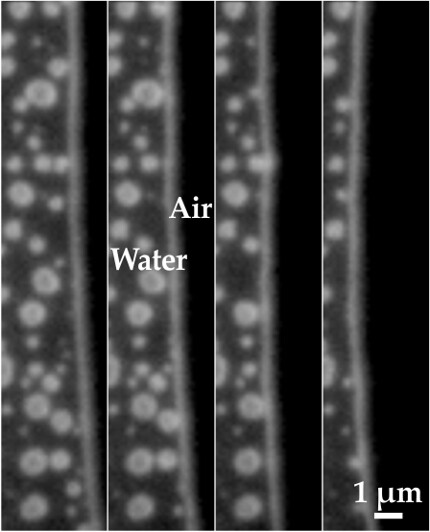

A close-up look at a surface under water might reveal squat bubbles hundreds of nanometers in diameter and a few tens of nanometers tall. The surface nanobubbles could be useful for reducing drag in microfluidic devices. But they have puzzled researchers because their longevity defies conventional wisdom: They can survive for days even though they should only last for microseconds, given the high internal gas pressure implied by their small size. The usual way to image them is with atomic force microscopy, which can easily mistake common contaminants, such as polymer droplets, for nanobubbles. That ambiguity and conflicting results from spectroscopic studies have led some researchers to question the existence of the diminutive bubbles. Now researchers at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, led by Claus-Dieter Ohl, have conclusively identified nanobubbles. Using a total-internal- reflection fluorescence microscope and a high-speed camera operating at 2000 frames per second, they watched suspected nanobubbles in a microchannel as air was pushed through the channel to displace the water. The snapshots here show a water-air-substrate boundary moving right to left through nanobubbles. Unlike polymer droplets or solid particles, the nanobubbles collapsed just as expected when the moving boundary touched them. The researchers found that molecular kinetic theory does a far better job of describing the collapse than bulk hydrodynamics. With that observation in mind, the group is working on a new microscopic model they hope will help answer why nanobubbles live so long. (C. U. Chan et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 114505, 2015, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.114505