Model sheds light on the language of color

DOI: 10.1063/1.3366229

Speakers of the same language generally agree whether two hues are different shades of the same color, in the sense that reddish orange and yellowish orange are both orange, or whether they are entirely different colors. And although speakers of different languages (especially pairs of languages whose speakers don’t interact) often disagree about what constitutes “the same color,” the disagreement isn’t as great as would be expected by chance. Statistical analysis of the World Color Survey’s data set—a collection of color categories in 110 languages from nonindustrial populations—found that the languages clustered together in color space to a greater degree than did sets of randomly generated categories. 1

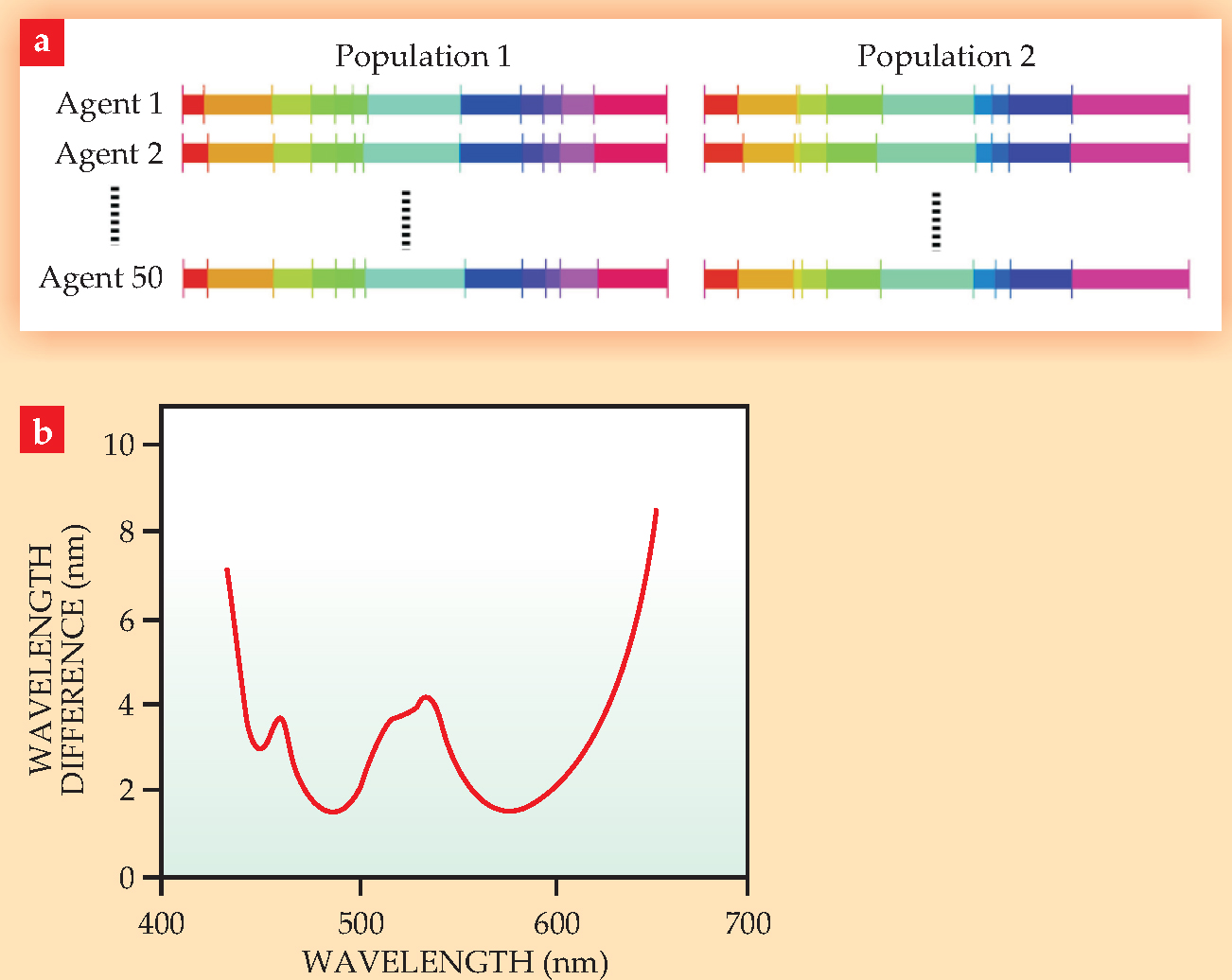

Researchers have used several computational approaches to understand how languages’ color categories develop. Among them is the work of Andrea Baronchelli, a physicist at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia in Barcelona, Spain, and his collaborators, who used a variant of the so-called naming game. 2 Artificial agents in a simulated population, beginning with no words for colors at all, were repeatedly tasked with describing different colors to one another. The individual agents independently invented words and categories and, based on the success or failure of their communications, adjusted their own categories and vocabularies to match those around them. (A communication was deemed successful if the word the speaker used appeared in the listener’s vocabulary and allowed the listener to identify which of several randomly chosen hues the speaker meant.) Eventually, after some 500 000 repetitions for a 50-person population, they came to a near consensus, in which everyone in the same population categorized colors in almost the same way, but those categories could differ markedly between noninteracting populations.

The idea behind the naming game is not new: The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote about the concept in the 1940s. But applying it to a continuous space, the visible spectrum, was an innovation. Curiously, the simulations—which accounted for none of the complexities of human societies or human vision—tended to stabilize at roughly 10-20 color categories, as shown in the figure, similar to the numbers found in real languages. But often those categories looked nothing like any human language.

Now, Baronchelli and colleagues have revised their model to include a real property of human vision, the just noticeable difference (JND; shown in the bottom panel), or wavelength resolution as a function of wavelength. 3

They ran a new set of computations in which their agents were not required to distinguish between colors that a real human couldn’t tell apart. And they found that the categories that resulted from their JND-based simulations displayed exactly the same degree of clustering as the World Color Survey results did. The researchers hope that the quantitative agreement with empirical data will pave the way for greater use of synthetic modeling in studying language development and other areas of cognitive science.

(a) Two simulated noninteracting populations partition the visible spectrum into color categories in different ways. (b) The just noticeable difference function represents the wavelength resolution of human vision.

(Adapted from

References

1. P. Kay and T. Regier, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9085 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1532837100

2. A. Puglisi, A. Baronchelli, V. Loreto, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7936 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0802485105

3. A. Baronchelli, T. Gong, A. Puglisi, V. Loreto, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 2403 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0908533107

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org