Mapping the hazard from induced earthquakes

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.3165

Much of Oklahoma and the vicinity of Dallas, Texas, face the same earthquake risk this year as the fault-ridden areas of California, according to a 28 March study by the US Geological Survey. It is the first time the USGS has mapped the hazard from both natural and induced earthquakes. Past forecasts have included only natural earthquakes.

The main cause of induced earthquakes is wastewater injection associated with gas and oil extraction—not, as commonly assumed, hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. When wastewater from the extraction process is disposed of underground—typically at least 1 km deep—it increases the pressure and can cause slippage along faults. In fracking, fluid is injected for the purpose of creating cracks, but it tends to involve less fluid for shorter times, so it causes fewer and smaller earthquakes than wastewater injection, according to Justin Rubinstein, the deputy chief of the USGS induced seismicity project and one of the study’s authors. (See also the article “Super fracking,” by Donald Turcotte, Eldridge Moores, and John Rundle, Physics Today, August 2014, page 34

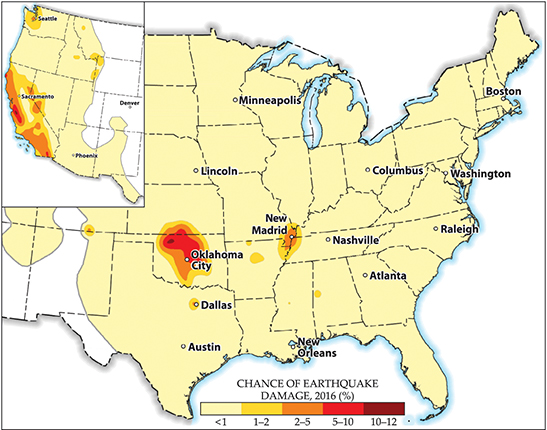

Since 2009 the number of induced quakes has jumped immensely, particularly in Oklahoma. Until then, the state saw two or so earthquakes each year; last year alone, some 907 earthquakes of magnitude 3.0 or greater were recorded. Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, and Texas also have areas with increased hazard levels due to induced earthquakes. In the highest-risk regions, the chance of earthquake damage this year is 10–12% (see the figure). The study’s authors define damage as cracking or worse occurring in buildings or other structures.

Chance of earthquake damage this year. The map of the western states (inset) is from the US Geological Survey’s 50-year model that considers only natural earthquakes. The map of the central and eastern US is a forecast based on both natural and induced earthquakes. (Adapted from figure 8 in 2016 One-Year Seismic Hazard Forecast for the Central and Eastern United States from Induced and Natural Earthquakes, USGS open-file report 2016-1035.)

Because changes in industrial injection activity can affect the incidence of induced earthquakes on a short time scale, the USGS scientists limited their predictions to 2016; they focused on the eastern and central US because induced earthquakes in the West are not a significant contributor to the earthquake-damage hazard in that part of the country.

There is no known seismological difference between natural and induced earthquakes, says Rubinstein. To date, such distinction is made through correlating earthquakes with industrial data. But at the least, daily information about wastewater-injection locations, times, volumes, and rates would be necessary to make a clear distinction, he says.

The maps in the new study supplement the USGS’s 2014 National Seismic Hazard Model forecast for natural earthquakes. That model projects 50 years out, a period chosen to be useful for setting building codes. Still, says Rubinstein, short-term risk could have implications for public safety, structural assessments, and regulatory practices.

The study’s authors say they will wait for feedback on the new maps before deciding how often to update them.

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org