Magic window uses liquid crystals to project images

Created in China at least 2000 years ago and then in Japan, magic mirrors look like simple flat bronze mirrors with ornate designs on the back. But shine a light directly at the front of one of them, and the back’s design is projected in the reflection.

After many years of puzzling over the mirrors’ optical properties, scientists had determined by the early 20th century that the mirror surfaces are not as perfectly flat as they appear. The front surface has height variations on the scale of hundreds of nanometers that match the pattern on the back. Incoming light is reflected in different directions depending on where it strikes the relief on the surface, and the resulting brightness pattern produces the desired design in the reflected image.

A Buddhist bronze “magic mirror” that was created in China or Japan in the 15th or 16th century is on display at the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Rob Deslongchamps/Cincinnati Art Museum

The last piece of the mathematical puzzle was completed by Michael Berry of the University of Bristol in 2005. He realized that the intensity of the light in each part of the design is related to the surface-height variations. So he described the height of the mirror as a function of position on the reflecting surface. The intensity is directly related to the Laplacian of that height function, which includes the curvature. Therefore, the brightness of the light at any given part of the design is determined by the curvature between adjacent protrusions

Still intrigued by the subject, Berry in 2017 theorized a magic window

Using Berry’s math and some advanced equipment, one has all the tools to make a magic mirror or window with any image. Now a team from the University of Ottawa in Canada and MIT led by Ebrahim Karimi has created a magic window that is completely flat. Instead of using varying thicknesses of glass to refract the light, the researchers’ magic window uses liquid crystals to impart optical phase shifts.

“It’s a really versatile approach because it allows us complete control,” says Felix Hufnagel, a member of Karimi’s team and the lead author of a paper

Liquid crystals can refract light in different directions depending on their orientation, so by turning the crystals, the researchers could shift the phase of the incoming polarized light. Liquid crystals’ interaction with light also depends on the light’s polarization: Different polarizations result in different phases in the outgoing light. And because of the crystals’ fluidity, different parts can have different orientations. The variation in orientations simulates the height variations in the original magic mirrors and windows.

Liquid crystals enable the creation of magic windows that produce hidden images.

Felix Hufnagel, University of Ottawa

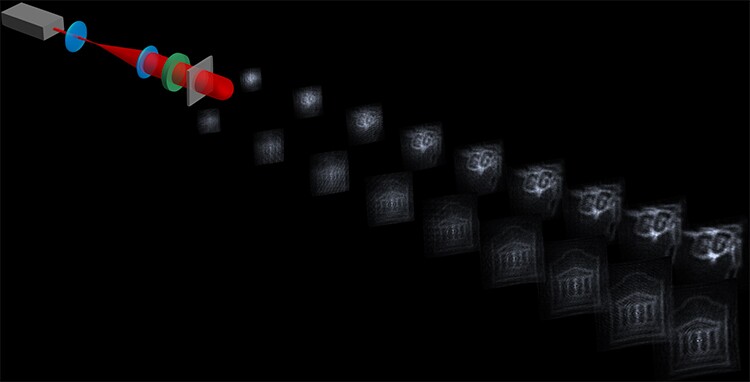

The Ottawa team used Berry’s technique to determine the orientation each pixel’s crystals would need to produce the desired image. Then, liquid crystals in the magic window were coaxed into their desired orientations using a digital micromirror device in combination with a UV alignment laser. That device is a 600 × 600 array of mirrors, each of which acts as a single pixel of the image. The mirrors can then be individually turned on or off, and that orients the pixel’s crystals. Using many small mirrors enabled the researchers to vary phases in a small area of the magic window and allowed for the projection of more complex images.

The researchers were able to use Berry’s Laplacian to realize their designs, because the combination of the incoming light’s polarization and the phases of the crystal replicates the height function in magic mirrors and windows. And since polarization is either right-handed or left-handed, the magic windows have two states that show the image. When hit by light with opposite polarization than the phases were tuned for, the image’s light parts become dark, and the dark parts become light.

The researchers used their liquid-crystal magic window to produce an image of the University of Ottawa logo.

Felix Hufnagel, University of Ottawa

Hufnagel and his Ottawa colleagues tested their new technology by projecting the logos of the university, the school’s sports teams, and the lab. The magic windows presented in the paper are wavelength and polarization dependent, but Hufnagel says that by using certain filters one could create a window that projects a design when sunlight shines on it.

Liquid-crystal magic windows are useful for things other than creating fun designs. The images created by the windows are stable over long distances, a highly desirable quality for three-dimensional screens. Akin to science fiction’s holograms, such screens are currently limited by images’ focal lengths. Since a flat magic window’s image can be discerned through many distances, a person could view the image from multiple locations.

The Ottawa team was partially drawn to the project by Berry’s academic interest in magic windows. Best known for his description of the Berry phase