Machine learning for image restoration

Fluorescence microscopy usually involves a trade-off between producing a quality image and having a healthy sample. Illuminating the sample with higher laser power strengthens the fluorescent signal but risks damaging biological samples and photobleaching fluorescent dyes. Imaging at a slower frame rate with lower laser power often produces high-quality images but sacrifices information in samples that move.

When such compromises hinder the recording of high-quality images, researchers often try to improve the images after the fact. To that end, Loïc Royer at the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub in San Francisco and Martin Weigert, Florian Jug, and Eugene Myers

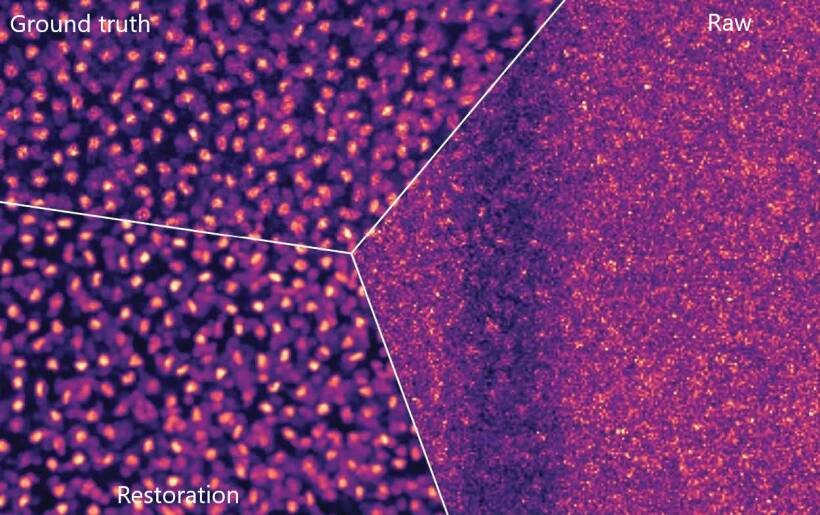

The first test for CARE was a flatworm whose muscles reflexively flinch under even moderate amounts of light. The researchers used dead worm samples to generate pairs of training images for the CARE network. Once it was trained, the network turned low-light images of worms with fluorescently dyed cell nuclei into high-resolution images, as illustrated in the figure.

CARE also improved feature identification in systems that were developing over time, such as beetle embryos and fruit-fly epithelia. The researchers maintained their ability to identify individual cell nuclei—and sometimes improved it—in images taken with 1/60 as much light as was needed without CARE. With less light used per image, researchers can record at a higher frame rate or for longer times.

Weigert, Royer, Jug, and colleagues investigated the reliability of CARE-restored images by training multiple networks and comparing their output images. Often, all were in close agreement, which indicated a reliable result. Disagreement between the networks allowed the researchers to identify possible inaccuracies in the restored images. (M. Weigert et al., Nat. Methods 15, 1090, 2018