Leon Lederman and Project ARISE

Leon Lederman, who died earlier this month

Leon Lederman engages students in the Chicago area at Saturday Morning Physics, an outreach program at Fermilab, in 1980.

Fermilab

Project ARISE (American Renaissance in Science Education) was the initiative that led to Lederman becoming an outspoken advocate for the Physics First movement, and its effects can still be seen in schools nationwide. Conceived in 1995 at a conference of educators and Fermilab researchers, Project ARISE was designed to address what Lederman perceived as the appalling state of physics education in US high schools. That year in a column for Physics Today

Lederman was not the first person to recognize the problem, and other attempts had been made in the preceding decades to improve science education in US schools. Initiatives like the Physical Science Study Committee, begun in 1956, and Project 2061 from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, started in the 1980s, had for years been suggesting a shift to more engaging, inquiry-based approaches to teaching physics. Individual teachers had implemented changes in their schools, and in 1971 Paul Hewitt had published the first edition of Conceptual Physics, his textbook aimed at teaching physics with minimal math. But as a prominent member of the physics community, Lederman had a platform to bring widespread publicity to science education reform and Physics First.

Project ARISE set out to create an integrated three-year science sequence that would equip students with critical thinking skills and make them, as Lederman put it, “comfortable with science for the rest of their lives.” The curriculum would be cohesive, with content from biology, chemistry, and physics cutting across all three years rather than being offered as three disjointed, sequential courses. Most importantly, the courses would shift students’ focus from memorizing facts to understanding concepts, the process of scientific thought, and science as a human endeavor.

Leon Lederman in 1989 demonstrates how electric fields accelerate particles.

Fermilab

Another key aspect of Project ARISE was changing the order in which information was presented. At the project’s inception, the sequence in more than 95% of high schools was biology, then chemistry, and finally physics. Lederman argued that the sequence should be reversed, with physics first. “Physics provides the underlying basis for chemical structure and atomic reactions,” he wrote in his 1995 Physics Today column, “and chemistry supplies the knowledge of molecular structure that is the basis of much of modern biology.” The reversal would be facilitated by a shift to a more conceptual approach to science. A traditional physics course requires math skills that a ninth grader may not have, but physics concepts can be taught to students in any grade.

Beyond reordering the three standard science courses, Project ARISE called for renaming them. Science I, Science II, and Science III would be mostly physics, chemistry, and biology, respectively. Lederman’s hope was that eliminating the usual labels would help teachers feel less bound to the standard curricula and be more willing to incorporate ideas from other scientific disciplines to create a logical flow of information. The renaming and integration strategy for the science courses did not make much headway. In a 2001 Physics Today column

A 2003 report

Not all the feedback was positive. Some students didn’t have the prerequisite math for physics in ninth grade, and teachers struggled with reducing the amount of math in the curriculum enough to accommodate their students. Schools had a hard time finding appropriate textbooks and teaching resources for less advanced students and hiring enough qualified physics teachers now that every student was taking physics. Some teachers struggled to implement the program while also covering the content required by state standards or needed for standardized tests.

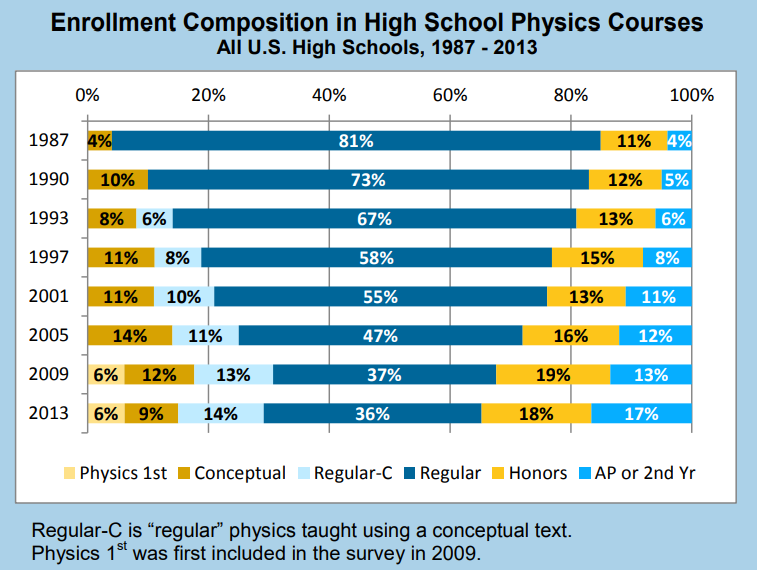

The proportion of US high school graduates taking Physics First, taking conceptual physics, or using a conceptual-physics textbook has grown over the past two decades.

AIP Statistical Research Center

Despite the positive experiences reported by teachers and students, the implementation of Physics First has been limited. In its most recent high school survey, the Statistical Research Center of the American Institute of Physics found that only 6% of high school physics students

In his 1998 report on Project ARISE