Laboratory experiment shows that noise can be lessened for LISA

DOI: 10.1063/1.3463616

Just as Maxwell’s equations imply that an accelerating charge produces electromagnetic radiation, Einstein’s theory of general relativity predicts that an accelerating mass produces gravitational radiation. As a gravitational wave propagates at the speed of light, it stretches space in one direction and compresses it in another. But because gravity is so weak, those distortions are minuscule, and extraordinary sensitivity is required to detect them.

The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) is a proposed mission to look for gravitational waves through their effect on the distances between three spacecraft. The spacecraft would form, in essence, a Michelson interferometer 5 million kilometers on a side—more than 10 times the distance from Earth to the Moon. Researchers hope to be able to measure oscillations as small as 10 picometers in the interferometer’s arm lengths.

Many technical challenges stand in LISA’s way. One of the biggest has involved laser phase noise: Even with the laser frequencies stabilized as much as possible, they still exhibit fluctuations that are a billion times larger than the signal. In 1999 John Armstrong, Frank Estabrook, and Massimo Tinto of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) presented the theory for a method, called time-delay interferometry (TDI), of eliminating that noise through signal processing. 1 Now, a team of JPL experimentalists led by William Klipstein has shown in a laboratory demonstration that TDI can indeed reduce LISA’s noise to the necessary extent.s 2

LISA and LIGO

Indirect evidence for gravitational waves is strong. Pulsars orbiting companion stars lose energy at exactly the rate predicted by general relativity. Researchers looking to detect gravitational radiation are less interested in proving the waves’ existence than in the information they can provide: about merging black holes, core-collapse supernovae, galaxy formation—and the first 380 000 years after the Big Bang, a period when the universe was opaque and from which no electromagnetic information survives.

Different sources produce gravitational radiation of different frequencies. Ground-based interferometers, such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), can be sensitive to frequencies from tens to thousands of hertz. (See the article by Barry Barish and Rainer Weiss in Physics Today, October 1999, page 44

LIGO doesn’t have a problem with laser phase noise because, as is typical for a Michelson interferometer, its arms are of equal length. The light returning from one arm contains exactly the same phase fluctuations as the light returning from the other, since it was produced by the same laser at the same time, so the fluctuations cancel. For LISA to benefit from the same level of noise cancellation, its arms would have to differ by no more than 3 m. But with each spacecraft in its own orbit about the Sun, its arms will naturally vary by 75 000 km. So the TDI plan is to reduce noise by adding and subtracting signals recorded at different times.

Arms control

If LISA were an equal-arm Michelson interferometer centered on spacecraft 1, the light returning from spacecraft 2 would be combined with the light returning from spacecraft 3, and the relative phase would be observed as constructive or destructive interference. Under TDI, the light returning from each of two unequal arms is instead combined with a portion of the outgoing beam, and the resulting phases are recorded as φ21(t) and φ31(t). If there were no phase noise, φ21(t) − φ31(t) would be the Michelson interferometer signal. In the presence of noise, φ21(t) contains the laser fluctuations produced at time t and time t − t 21 (where t 21 is the time light takes to make the roundtrip between spacecraft 1 and 2), and φ31(t) contains the fluctuations from times t and t − t 31. To get rid of the noise, one subtracts the phase for each arm offset by the other arm’s roundtrip time:

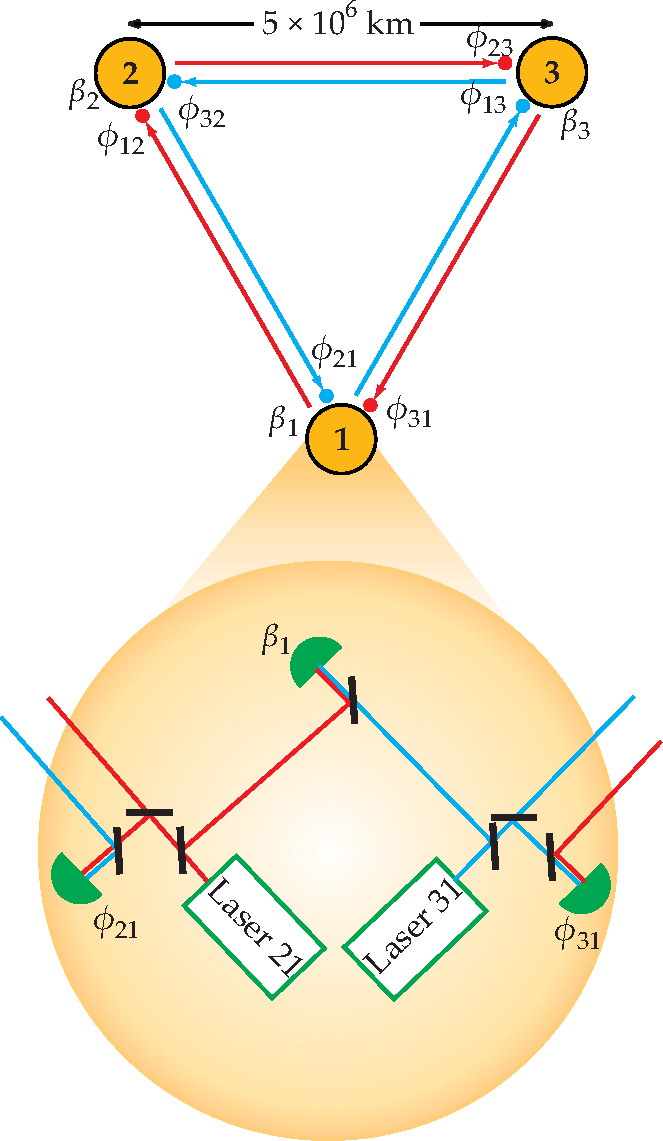

Actually, the LISA design (shown schematically in figure 1) has separate lasers directed at spacecraft 2 and 3. But with their relative phase measured and recorded (as β1(t)), the same information is available as if one laser were used for both arms. And two more lasers are at the far ends of the arms — the spacecraft are so far apart that using mirrors to reflect the light back would leave no measurable intensity at the end of the roundtrip — and their phases relative to the incoming beams are recorded also. With a final pair of lasers making the link between spacecraft 2 and 3, researchers can derive three different TDI Michelson interferometer signals, as well as other useful combinations.

Figure 1. LISA laser links. Three spacecraft form a triangle 5 million km on a side. Laser beams (red and blue) pass in each direction between each pair of spacecraft. Three phase measurements (green semicircles) are recorded as a function of time on each spacecraft: one between the spacecraft’s two outgoing lasers (β,(t)) and two between pairs of incoming and outgoing lasers (φ21(t) and φ31(t)). From the nine measured phases, researchers can derive a signal equivalent to that of an equal-arm Michelson interferometer centered on any of the spacecraft.

(Adapted from

For data recorded on different spacecraft to be combined, each craft must have its own clock, and the clocks must be synchronized. But clocks light enough for spaceflight are not nearly accurate enough for LISA’s needs. Instead, the plan is to remove noise due to clock error in a further signal-processing step. Each laser beam is encoded with its local clock’s signal, so the interspacecraft phases (φ12, φ21, and so on) contain information about the relative clock noise, which can then be removed.

Testing TDI

The JPL demonstration was designed as a system-level test of both the TDI technique and the high-precision phase meter the group had developed. 3 In an effort to distill TDI’s essential features, the researchers simplified their system in many ways compared with the planned LISA configuration. They used two laboratory benches—each representing a spacecraft—instead of three; two laser beams in each direction passed between the benches. They ignored, for the time being, the complication of the ever-changing Doppler shift between the spacecraft. And they did nothing to simulate light’s 17-second travel time between the LISA spacecraft: The only time delay in their time-delay interferometry was a few hundred nanoseconds, mostly due to the electronics. “But,” notes the group’s Brent Ware, “the mathematics is the same.” Separately, Guido Mueller and colleagues at the University of Florida have also developed a laboratory LISA simulator, and they do include the long time delay. They capture each laser beam en route and generate an identical beam 17 s later. 4

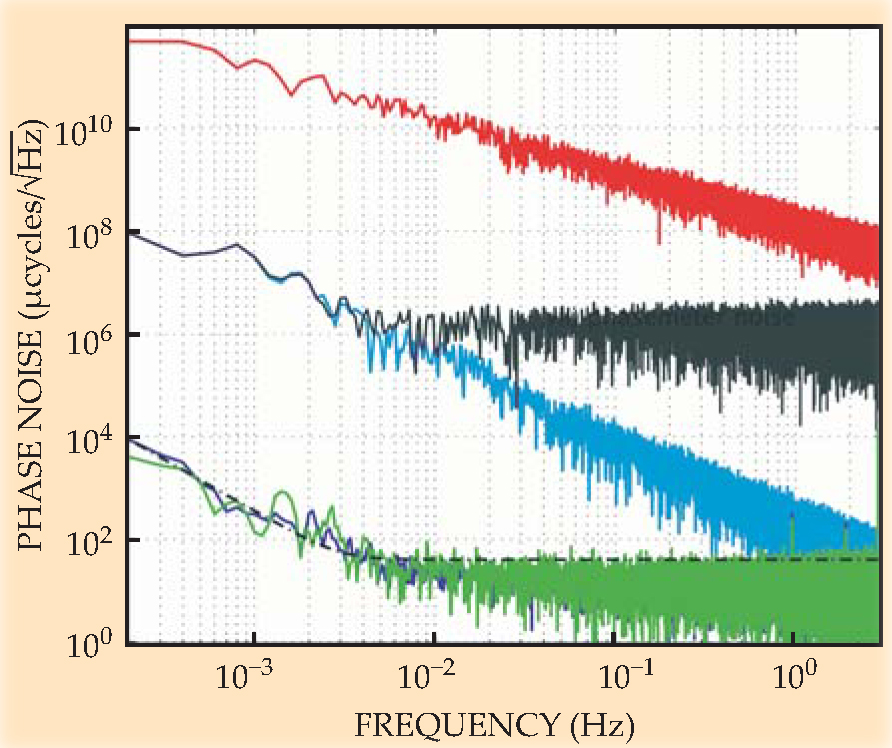

To capture the properties of LISA in a lab environment that lacked picometer-level stability, and to help prevent noise sources from canceling accidentally, the JPL researchers looked at a combination of signals corresponding to a Sagnac interferometer, which measures the phase difference between light beams propagating clockwise and counterclockwise around a loop, not a Michelson interferometer. Figure 2 shows the recorded noise spectra, the fluctuations in phase measurements on the time scales of the waves LISA could detect. The red curve at the top, the raw laser phase noise, shows what they’re up against. The black dotted line eight or nine orders of magnitude below shows LISA’s required sensitivity.

Figure 2. Noise spectral densities measured in a LISA laboratory test. Shown are the levels of phase fluctuation in the raw laser signal (red) and in linear combinations of signals designed to cancel first the phase fluctuations (black), then the clock drift (blue), and finally the clock fluctuations (green). The processed signal not only satisfies LISA’s sensitivity requirements (black dashed line) but also coincides with the noise limit of the laboratory system (purple curve, mostly obscured).

(Adapted from

The black solid curve represents the linear combination of signals designed to cancel all the laser phase fluctuations. The remaining noise is due to clock error, which must be canceled in two steps: one that accounts for the linear offset between the clock signals and a second that corrects for random clock fluctuations. The blue curve shows the first step, and the green curve, just below the LISA requirement, shows the second. The purple curve, mostly obscured by the green one, shows the JPL system’s limitation, the noise measured in a different test run during which the clocks and lasers were all phase-locked. The researchers are working on improving that limit so they can better understand TDI’s potential.

There is much more work to do before LISA is ready. And the mission’s future depends heavily on the outcome of the National Academy of Sciences’ Astronomy and Astrophysics Decadal Survey, a ranking of funding priorities for the next 10 years, expected to be announced later this summer. If LISA ranks highly, the spacecraft could be launched by 2021; if not, the mission could be delayed indefinitely. But, says Ware, work on TDI will pay off eventually. “Whether LISA comes out on top or not, someone will eventually build a gravitational wave detector in space. And it will look like LISA.”

References

1. M. Tinto, Phys. Rev. D 59, 102003 (1999); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.59.102003

J. W. Armstrong, F. B. Estabrook, M. Tinto, Astrophys. J. 527, 814 (1999).2. G. de Vine et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 211103 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.211103

3. D. Shaddock et al., Laser Interferometer Space Antenna: 6th International LISA Symposium, AIP, Melville, NY (2006), p. 654.

4. R. J. Cruz et al., Class. Quantum. Grav. 23, S751 (2006); https://doi.org/10.1088/0264-9381/23/19/S14

S. J. Mitryk, V. Wand, G. Mueller, Class. Quantum. Grav. 27, 084012 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1088/0264-9381/27/8/084012

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org