IR spectra reveal water vapor in regions where terrestrial planets form

DOI: 10.1063/1.2930720

The nascent Sun did not shine on planets; rather, it illuminated a thick disk of material from which Earth and its solar-system companions later condensed. Figure 1 is an artist’s rendition of what the disk might have looked like. Comets, in their wide-ranging travels through our solar system, gather samples preserved from the disk that ultimately gave rise to Earth. For that reason, much excitement has attended recent missions in which probes smashed into comets and the resulting debris was closely analyzed.

Figure 1. A protoplanetary disk as rendered by an artist. A young star shining brightly in the center is surrounded by material that will eventually condense into planets and other solar-system objects.

(Courtesy of Robert Hurt, NASA/JPL-Caltech.)

Still, little is known of the structural and evolutionary details of circumstellar, or protoplanetary, disks. In March of this year, two teams of astronomers independently reported observations that could complement the cometary studies: detailed IR spectra of water vapor and organic molecules from regions of protoplanetary disks where terrestrial planets might someday form. The spectra, taken by instruments aboard the Spitzer Space Telescope and at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, were obtained by John Carr (US Naval Research Laboratory) and Joan Najita (National Optical Astronomy Observatory) 1 and by Geoffrey Blake (Caltech), his graduate student Colette Salyk, and coworkers. 2 Together, the two collaborations considered three systems, each of which includes a young star whose mass is comparable to that of the Sun. But each of the groups has several additional spectra on hand. It’s early days yet for a research program that may help answer such fundamental questions as how water was delivered to our home planet.

Sharpening Spitzer

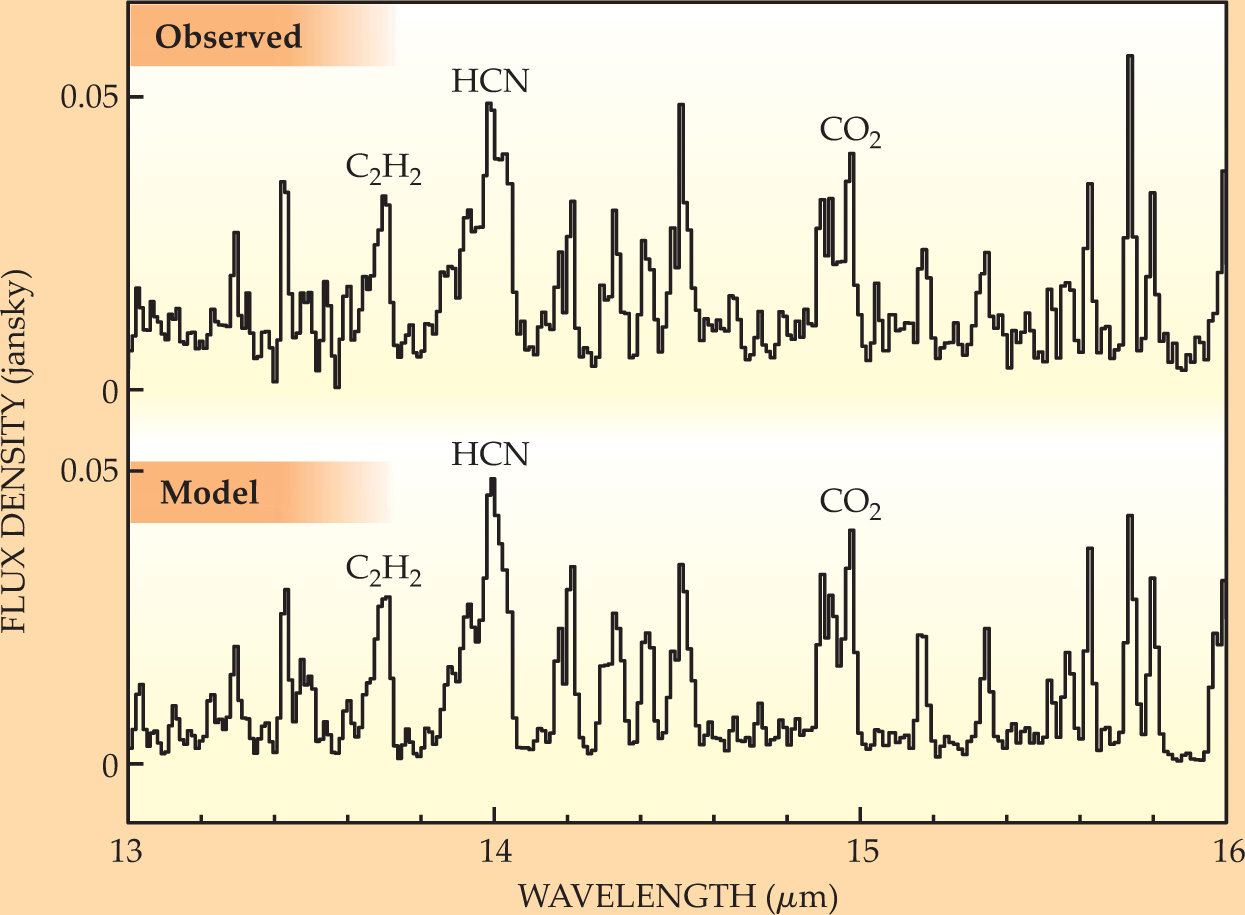

The liquid-helium-cooled IR spectrometers in Spitzer orbit above Earth’s atmosphere and are much more sensitive than their ground-based counterparts. Moreover, the space-borne instruments can obtain spectra for circumstellardisk compounds—carbon dioxide, for example—that are masked by our atmosphere. Figure 2 shows a portion of the spectrum taken by Spitzer ’s infrared spectrograph of the circumstellar disk encircling the star AA Tauri; it includes many peaks corresponding to water emission but also peaks corresponding to other gases.

Figure 2. Emission peaks from acetylene (C2H2), hydrogen cyanide (HCN), carbon dioxide (CO2), and water (the unlabeled peaks) are evident in this piece of a Spitzer IR spectrum. The model assumes the emitting gases are in thermal equilibrium. A jansky is 10−26 W m−2 Hz−1.

(Adapted from ref. 1.)

To interpret such spectra—to infer the temperatures, locations, and so forth of the emitting molecules—one needs a model. Both Blake’s group and Carr and Najita assumed each of the radiating species to be in thermal equilibrium and fitted the emission lines with a handful of parameters. The many peaks in the observed spectra constrain the model parameters well enough to yield impressive accord between model and observation (see figure 2).

Unfortunately, Spitzer ’s spectral resolution is not good enough to determine the locations of the emitting gases from their Doppler shifts. As Blake explains it, “You can get a good estimate of the temperature, the amount of gas, and the emitting area from the Spitzer data, but the range of radii corresponding to the emitting area is ambiguous.” For that reason the Blake team supplemented its Spitzer observations with higher resolution, near-IR spectra obtained with the NIRSPEC instrument at Keck. Together, the Spitzer and Keck measurements gave inner and outer radii for the emitting molecules. The observations reported by both research teams are consistent with abundant water and other gases having a temperature of order 1000 K. In the Carr and Najita work, those gases include organic molecules such as acetylene. Blake and colleagues have also seen organics, but their paper focuses on water and the hydroxyl radical. Both groups conclude that the molecules they observe are located within a few astronomical units (1 AU is the Earth-to-Sun distance) of the protoplanetary disk’s central star. As in our solar system, that region is too small for a would-be planet to gather up much mass and too hot to accommodate the ice that might accrete into the core of a gas giant. It’s just where terrestrial planets would form.

Delivering the goods

It is no surprise that water vapor exists in the terrestrial-planet-forming regions of circumstellar disks. Nonetheless, notes David Stevenson, a planetary scientist at Caltech, the newly reported spectra demonstrate that physicists are beginning to get at protoplanetary-disk structure by learning where the water is and whether the water is in the vapor or ice phase. As they learn more, they may be able to shed light on a number of questions concerning disk structure and dynamics.

One such issue concerns the transport of water in the plane of the disk. As you move away from the central star, the temperature falls. Eventually you encounter a region, fancifully called the snow line, beyond which water exists as ice. (In our solar system, the snow line is in the asteroid belt.) Water vapor that diffuses outward across the snow line from inner regions of the protoplanetary disk condenses and is unable to diffuse back into the region whence it came. Thus the existence of the snow line implies a mechanism for removing water from the disk’s inner region. On the other hand, icy solids circulating in the viscous disk experience a headwind, so they lose angular momentum and drift toward the central star. Once they cross the snow line, they sublimate and replenish the water vapor in the inner disk. Which mechanism is more effective, drying or replenishing? Additional measurements of water-vapor and water-ice abundances may answer that question, particularly if observers can obtain data for a number of disks whose ages are known.

Just how Earth received its life-sustaining water is a matter of considerable debate in the planetary science community. Although some scientists argue that Earth gathered its water from its local environment, the majority view is that the water was delivered by agents from afar, such as comets. That view, though, needs to confront an empirical embarrassment: The ratio of deuterium to hydrogen (D/H) measured in three high-eccentricity comets is much higher than that observed in Earth’s oceans. Perhaps, though, water was delivered by icy bodies that originated closer to Earth, near the region where Jupiter formed. In that somewhat warmer region, the D/H of the condensed ice may be less than that observed in comets and more in line with our planet’s value. Ongoing analyses of Spitzer and Keck spectra should further specify the quantity and distribution of water in the inner protoplanetary disks. They could be of significant value to scientists modeling the delivery of water to Earth. But the data will in all likelihood not be able to distinguish HDO (as opposed to H2O) peaks.

The abundance of water and organic molecules seen by Spitzer was surprisingly high—at least to Najita, who, with Alfred Glassgold, has modeled the environment probed by Spitzer . The IR-emitting molecules, she points out, are near the surface of the circumstellar disk, a relatively hot region illuminated by the central star and bathed in UV and x-ray radiation that suppresses molecular formation. Thus the relatively large quantities of water and organics might indicate both substantial molecular synthesis within the circumstellar disk and a transport process that brings material from the disk’s central plane to its surface. Or it just might indicate chemistry not originally envisioned by Najita and Glassgold. That’s a possibility the two are currently puzzling out.

Spitzer is not finished collecting IR spectra for protoplanetary disks. During its final cryogenic observing cycle, which begins this summer, Carr and Najita will join forces with Blake’s team to observe the terrestrial-planet-forming regions of some 40 disks. The Herschel Space Observatory , scheduled for launch in October of this year, will look for cold water vapor in the outer parts of protoplanetary disks. And qualitatively new information may be provided by the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, currently under construction in Chile and scheduled for completion in 2012. At least for distances beyond about 10 AU or so, ALMA’s impressive resolving power should provide astronomers with their first look at the distribution of HDO.

References

1. J. Carr, J. Najita, Science 319, 1504 (2008).https://doi.org/SCIEAS

10.1126/science.1153807 2. C. Salyk et al., Astrophys. J. 676, L49 (2008).https://doi.org/ASJOAB

10.1086/586894