Inverted kinetics seen in concerted charge transfer

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4220

Just as a round stone rolls faster on a steep slope than on a gentle one, a chemical process speeds up when it’s made more energetically favorable. At least, that’s what usually happens. But 60 years ago when Rudolph Marcus developed his pioneering theory for electron transfer, he found that in a certain region of parameter space, increasing the driving force—the drop in free energy between the initial and final states—should actually slow the transfer down. 1

That surprising prediction—the so-called Marcus inverted region—was experimentally confirmed

2

in 1984, and in 1992 Marcus was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his theory (see Physics Today, January 1993, page 20

Electron transfer underlies all of oxidation–reduction chemistry, including corrosion, combustion, electrochemistry, and ionic bonding. In photovoltaic cells, the creation and recombination of free electrons and holes are both examples of electron transfer. Engineering a photovoltaic system to reside in a Marcus inverted region can reduce the rate of recombination and enable the extraction of more energy more efficiently.

But electron transfer by itself doesn’t involve the making or breaking of chemical bonds that are necessary for manipulating molecular identity or storing energy as chemical fuel. Now James Mayer, Sharon Hammes-Schiffer (both at Yale University), Leif Hammarström (Uppsala University in Sweden), and their colleagues have observed the signature of a Marcus inverted region in a different type of reaction that does rearrange a molecule’s atoms. 4 Rather than the transfer of a single electron, their reaction involves the simultaneous transfer of an electron and a proton—that is, a hydrogen nucleus. Such concerted proton–electron transfer is known to be important in biology, solar fuels, and chemical synthesis.

Up is down

Marcus theory stems from the insight that the rate of a charge-transfer process depends critically on what’s going on in the solvent or other surrounding medium. In water and other polar solvents, for example, the negatively charged ends of solvent molecules are drawn to positively charged regions of a solute molecule, and vice versa. When charge is redistributed among one or more solute molecules, the energetically preferred solvent configuration changes.

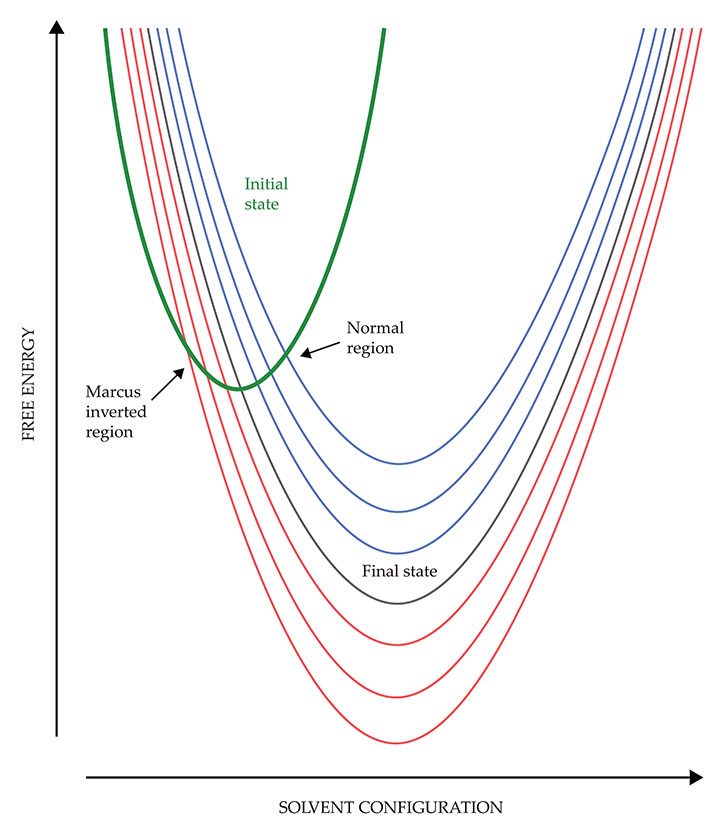

A full representation of the solvent configuration would require a many-dimensional space, but the key features can be collapsed onto a single coordinate, as shown in figure

Figure 1.

According to Marcus theory, a charge-transfer reaction can proceed only at the point where the free-energy curves of the initial and final states intersect. In the normal region of parameter space, lowering the final-state free energy (as represented by the series of blue parabolas) also lowers the free energy of the crossing point, and the reaction speeds up. But in the Marcus inverted region, lowering the final-state free energy (red parabolas) raises the crossing-point free energy, and the reaction slows down.

The law of conservation of energy dictates that charge transfer can proceed only when the initial and final states have the same free energy at the same solvent configuration—that is, at the point where their parabolas cross. In most cases, the crossing point is not at the bottom of the initial-state free-energy curve, so it represents a free-energy barrier the system must surmount. The higher the barrier, the slower the reaction.

The seven final-state parabolas in figure

Defying diffusion

Early attempts to experimentally observe the inverted region came up short. As the driving force was increased, the rate of electron transfer initially increased, as expected—but then it leveled off and never clearly decreased. The problem was diffusion: In an electron transfer between two molecules in solution, the measured rate depends not only on the intrinsic transfer rate, as described by Marcus theory, but also on how frequently the donor and acceptor molecules approach each other. When the intrinsic rate is fast, as it is at the onset of the inverted region, the transfer occurs essentially immediately every time a donor and an acceptor get close enough. The rate-limiting step is diffusion, and the intrinsic transfer rate is obscured.

In 1984 John Miller, Lidia Calcaterra, and Gerhard Closs solved the diffusion problem by putting their electron donor and acceptor on the same molecule, connected by a rigid molecular spacer. By guaranteeing that the donor and acceptor would always be in close proximity, they overcame the effect of diffusion and achieved the first unambiguous demonstration of a Marcus inverted region. 2

In their new paper, Mayer and colleagues also looked at intramolecular charge transfer, this time in a family of three-part molecules called anthracene-phenol-pyridines.

4

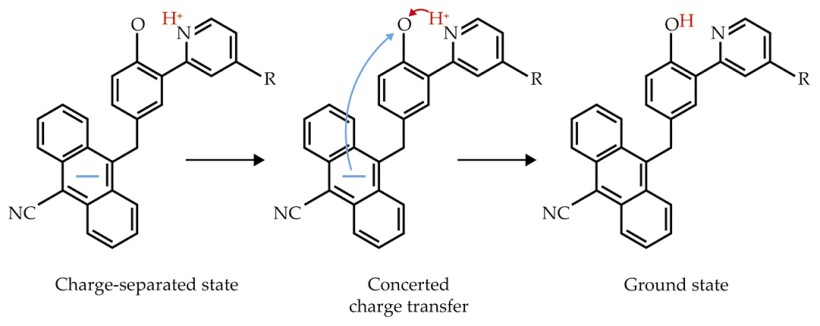

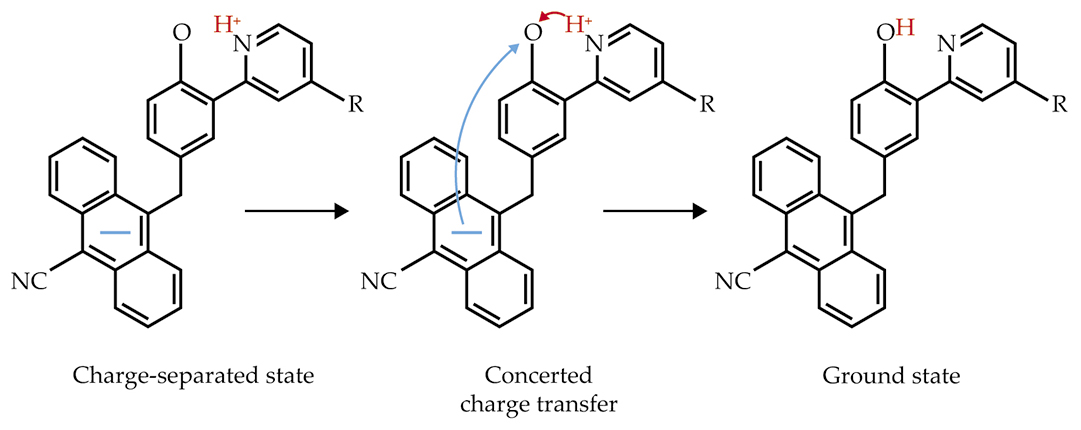

Optically exciting an anthracene-phenol-pyridine can give rise to a metastable charge-separated state, as shown in figure

Figure 2.

In a three-part molecule called an anthracene-phenol-pyridine, concerted movement of a proton and an electron characterizes the spontaneous relaxation from a charge-separated state to the ground state. Placing different molecular groups at the position marked “R” changes the relative free energies of the initial and final states. The molecules with the larger free-energy changes show slower rates of charge recombination—the signature of a Marcus inverted region.

The first anthracene-phenol-pyridines were prepared several years ago by Miriam Bowring, then a postdoc in Mayer’s group, as part of an effort to push the limits of how fast concerted proton–electron transfer could go.

5

In the unsubstituted molecule (without the CN or R groups in figure

Proton potential

But it wasn’t clear that the inverted region would be experimentally accessible. Indeed, theoretician Hammes-Schiffer and her colleagues made the case a decade ago that it shouldn’t be. 6 The crux of the argument is that when the H+ ion moves, it can set a molecular vibration in motion and leave the charge-recombined molecule in a vibrationally excited state. Because a molecular vibration can be approximated by a quantum harmonic oscillator, with a ladder of eigenstates equally spaced over a wide energy range, there’s always a state that’s close to the right energy for a barrierless reaction. Increasing the driving force, they predicted, should increase the number of vibrational quanta in the final state, with the Marcus inverted region always just out of reach.

Nevertheless, observation of the barrierless reaction was encouraging, and Mayer and colleagues were eager to explore it further. When Bowring presented her results at a conference in Sweden in 2014, their group struck up a collaboration with Hammarström, whose lab was ideally equipped to perform the necessary ultrafast measurements. Giovanny Parada, then a graduate student at Uppsala and now a postdoc with Mayer, also joined the project.

Parada used his synthetic-chemistry expertise to expand the family of anthracene-phenol-pyridines. By attaching different molecular groups at the position marked “R” in figure

But what about vibrational excitations—why weren’t they blocking access to the Marcus inverted region? It turned out that the charge transfer was exciting a molecular vibration, just not with as many quanta as needed to get to the zero-barrier reaction. To see why, Hammes-Schiffer and her student Zachary Goldsmith delved into the quantum details. They found that the wavefunction of the initial charge-separated state had a negligible overlap integral with the vibrational state that would have yielded the zero-barrier reaction. The transition to that state was therefore inhibited. The quantum properties were a consequence of the shape of the potential felt by the proton, so designing molecules with an eye toward that potential could be a route to finding the Marcus inverted region in other concerted charge-transfer systems.

But for now, nobody knows how common or rare the effect might be. The Yale–Uppsala collaboration is on the case, with the theoreticians exploring large regions of parameter space to guide the experimenters’ next choice of molecules to study. “We’d like to think that the phenomenon will prove to be widespread,” says Mayer, “because then it could be used in more complex systems to tackle challenges such as solar-energy conversion.” Because concerted proton–electron transfer is common in biology, in processes such as photosynthesis and respiration, another intriguing question is whether nature already exploits the Marcus inverted region in biological pathways. If so, understanding the inverted kinetics could be key to mimicking those functions in synthetic systems.

References

1. R. A. Marcus, Discuss. Faraday Soc. 29, 21 (1960). https://doi.org/10.1039/DF9602900021

2. J. R. Miller, L. T. Calcaterra, G. L. Closs, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106, 3047 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00322a058

3. See, for example, P. L. Houston, Chemical Kinetics and Reaction Dynamics, Dover (2006), p. 155.

4. G. A. Parada et al., Science 364, 471 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw4675

5. M. A. Bowring et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7449 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.8b04455

6. S. J. Edwards, A. V. Soudackov, S. Hammes-Schiffer, J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 14545 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1021/jp907808t

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org