Individual molecules are entangled for the first time

The success of efforts to build fast, reliable quantum computers and simulators depends on the devices’ ability to maintain and exploit the delicate feature of quantum entanglement, in which multiple particles behave as a single quantum system. Researchers have explored various physical platforms—including ions, neutral atoms, and superconducting circuits—that provide both the robustness against environmental disturbances and the high level of control that is needed to harness entanglement.

Molecules represent a challenging but potentially rewarding addition to the lineup of quantum platforms. Compared with atoms, molecules have additional degrees of freedom—rotational and vibrational states—that can be used to encode and process quantum information. Yet that complexity also makes molecules harder to reliably control. Now two teams of researchers, one led by Lawrence Cheuk of Princeton University and one led by John Doyle of Harvard University, have entangled individual molecules for the first time.

Single calcium monofluoride molecules are trapped in an optical tweezer array and are moved into closely separated pairs. The proximity allows the molecules to interact through the long-range electric dipolar interaction and become entangled.

Adapted from C. M. Holland, Y. Lu, L. W. Cheuk, Science 382, 1143 (2023)

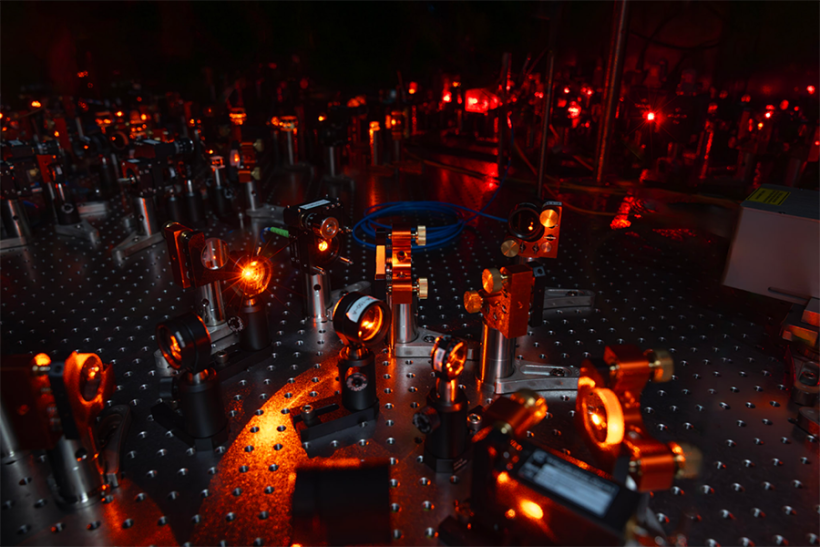

The two groups’ achievements rely on recent advances in trapping and cooling single atoms and molecules with lasers. Working with beam arrays known as optical tweezers that are focused to micron-size spots, the researchers isolated individual molecules of the highly polar compound calcium monofluoride and cooled them to microkelvin temperatures. Reaching that ultracold regime enabled the optical tweezers to retain a hold on the molecules. To generate entanglement, the Cheuk and Doyle teams forced pairs of the trapped CaF molecules together and nudged them to interact via long-range electric dipolar coupling. The researchers demonstrated that the molecule pairs remained entangled when separated.

The molecular laser-cooling setup used by the Princeton University group.

Rick Soden, Princeton University

The researchers plan to improve on their technique in several ways, such as by increasing the probability of capturing a molecule in the optical tweezer. The current results already demonstrate the building blocks that would be needed for future applications such as quantum information processing and quantum simulation. (C. M. Holland, Y. Lu, L. W. Cheuk, Science 382, 1143, 2023