Image classification approaches the speed of light

Distinguishing letters is usually easy for the human brain. The lines on p and d are flipped, for example, and the curves in an a and the cross of a t are dead giveaways. As we read text on a page, neurons in our brain fire, propelling sensory input through complex networks that allow us to interpret and categorize the letters.

Computer chips, particularly graphics processing units (GPUs), can achieve the same task with neural networks of their own. When used for applications such as facial recognition, GPUs transform the impinging optical information into electrical signals. Then the chips process those signals on a schedule, with a clock directing them to perform certain tasks at specific times. Tick: Multiply two matrices together. Tock: Store the information in a memory module. Tick: Retrieve the information. Tock: Perform another operation. And on it goes.

GPUs are powerful and easy to configure, but the clock cycle limits their speed. And placing data in memory and reading from that memory for subsequent computations sacrifices not only speed but also, potentially, the security of the data.

In contrast, photonic deep neural networks (PDNNs) can absorb optical data and process it as is, avoiding the need for a memory module and circumventing any privacy issues. They aren’t clock-based, so computations can theoretically take place at the speed of light.

The concept of a PDNN isn’t new, but Firooz Aflatouni of the University of Pennsylvania and his team have provided a crucial step toward widespread use by implementing the technology entirely with on-chip photonics. The researchers built and trained a PDNN

Peeling apart the layers of a PDNN

Photonic hardware uses light as the computational medium to perform calculations, which makes its potential speed much faster than that of its electronic counterpart. Analyzing images with photonics makes intuitive sense because the data are kept in their native domain. By designing photonic systems in the right way, the only constraints could come from the speed of light itself. But limitations in scalable, on-chip technology and nonlinear optical calculations, as well as the loss in photonic devices, have stalled large-scale progress.

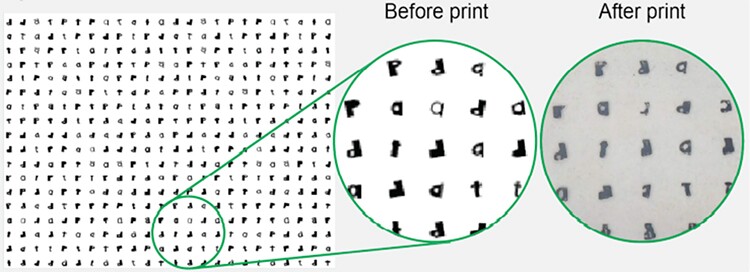

Figure 1. A sample of handwritten letters before and after printing on a transparent slide. These were used to train and test the PDNN.

F. Ashtiani, A. J. Geers, F. Aflatouni, Nature 606, 501 (2022)

To train and then test their network, Aflatouni and collaborators printed transparency slides with handwritten letters, a sample of which is shown in figure 1. By shifting the slides under a source of light, the researchers progressed through a list of letters that formed images on an input pixel array of the chip, seen on the left in figure 2.

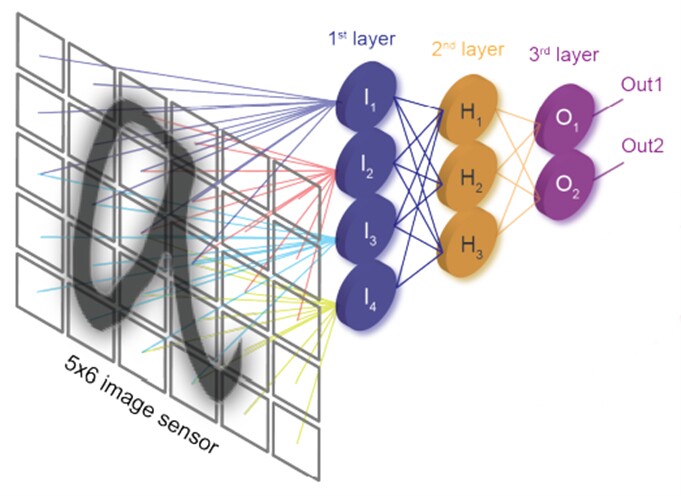

From there, the light is captured in waveguides (the colorful lines) and passed to three subsequent layers of neurons. Each neuron, shown in blue, orange, or purple, is fully connected to the outputs from the previous layer. They capture the incoming optical information and transform it, funneling it into fewer outputs before passing it to the next layer. In the final layer, the neurons output their best guess at the handwritten letter.

Figure 2. The input pixel array is shown on the left, with the letter a as an example. Information from each pixel passes through waveguides to the network, which consists of three layers of neurons.

F. Ashtiani, A. J. Geers, F. Aflatouni, Nature 606, 501 (2022)

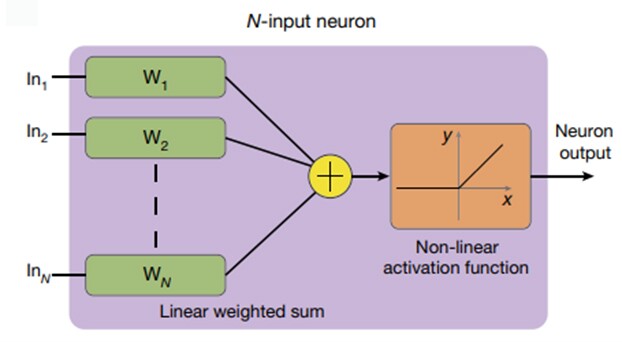

Figure 3 shows a peek inside an individual neuron. The amplitude of the input optical signal (left) is multiplied by a certain factor with a linear function (in green). The light is then converted to a photocurrent using a photodiode and added to other, similarly connected inputs to generate a weighted sum, represented by the yellow plus symbol.

That weighting is crucial for the scalability of the design. As the light travels through the network, its energy will drop with each layer. By weighting the signal at each stage, the design can add more layers of neurons in the future without losing important information. “We pumped each of our neurons with a little bit of optical energy,” says Aflatouni. “So regardless of where the neuron is, whether it’s the first layer, second layer, or what have you, they all are capable of providing the same level of output.”

Figure 3. Inside one of the neurons, which are shown as circles in figure 2. The inputs enter the neuron, where they are multiplied by a weight determined from training the PDNN. The weighted sum, shown by the yellow symbol, is passed to the nonlinear activation function, which creates the final output.

F. Ashtiani, A. J. Geers, F. Aflatouni, Nature 606, 501 (2022)

The weighting factor comes directly from training the PDNN, which the researchers did with a digital neural network with the same architecture as the photonic version. As the neural network cycles through letters, it learns which weights to apply and where to apply them. From there, the weighted sum is amplified and converted to a voltage, then passed through a nonlinear activation function.

For their chip, the researchers created the nonlinear activation function using the electro-optic nonlinear response of a micro-ring modulator. The modulator acts like a barrier, creating a piecewise output function. If the input voltage is high enough, the output power of the neuron follows a linear slope based on that voltage. Otherwise, the output power remains at zero. In the final layer of neurons, the output of the function corresponds to which letter the chip has recognized.

Lightning-fast letters

Although the PDNN hosts optoelectronics requiring some conversions between optical and electrical signals, the optical components make it very fast compared with electronic neural networks. The end-to-end classification time, or the time between forming an image on the chip and getting an answer, takes 570 picoseconds, the duration of roughly one clock cycle in a GPU. The computer chip would have to cycle through billions of clock cycles to achieve the same result.

“In terms of total inference time, this paper is breaking a record, as far as I know, by having subnanosecond classification time going through a few layers,” says Charles Roques-Carmes, a postdoctoral associate in the Research Laboratory of Electronics at MIT who was not involved with the study.

The photonic chip’s classification accuracy is comparable to that of its electronic counterpart. It achieved 93.8% accuracy for distinguishing between two letters and 89.8% accuracy for four letters, whereas a standard neural network obtained 96% accuracy for the same four-letter dataset. The gap between the two stems from the difference in the type of signal used. For electronic chips, logic one and logic zero are far apart, and noise is unlikely to convert one result to another. But the analog nature of PDNNs results in more in-between levels and higher inaccuracies.

Private, hybrid, and scalable systems

PDNNs offer many advantages, especially in terms of privacy. Because images are seen and characterized without being stored, stealing information by hacking into a chip’s memory becomes impossible. However, PDNNs are still less configurable than GPUs. Each photonic network must be designed with its specific application in mind. But by working together, the two technologies could form powerful hybrid systems. “If you have the computer chip and you have the photonic chip, the photonic chip can do some processing of the data that will make the electronic chip go a lot faster,” says Aflatouni.

For example, in facial recognition software, PDNNs could narrow the search by eliminating images without faces. They could also pick out the important areas within an image and then pass those along to a computer chip to analyze in more depth.

The Aflatouni team’s chip was a prototype, and characterizing the letters was a way to benchmark its effectiveness. The researchers are now working on more sophisticated PDNNs that can read larger pixel arrays as inputs and output more than four categories.

“This work is quite important for giving people more faith in the scalability of PDNN approaches,” says Roques-Carmes. “It will probably redirect a lot of research toward the field.”