How Princeton connects researchers to investors

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.5001

Your latest results from the lab are looking really good. Spectacular, in fact. You know they’re far better than anything you could get from current off-the-shelf technology, and you start to think, maybe you could commercialize this. But you’d need to prove out a few more things, and prototype it, and that takes money, more than you’ve got in your current grant. And once you have the thing, how do you sell it? Where would you even start?

Starting a technology business is harder than ever before. The implosion of the telecom bubble has left venture capitalists with a lasting reluctance to invest in tech startups. That reluctance has forced aspiring technology businesses to find other ways to get off the ground. Young companies need space and equipment to refine their ideas, a manufacturer to make the product, and a sales and marketing team to sell it. All of this takes money and skill sets that researchers tend to lack.

But the money is out there—it’s just gun-shy. And the manufacturers and marketers who want to work with new, promising technology businesses exist—they just need to believe that a fledgling company has a problem-solving product. When it’s posed in that way, the funding conundrum becomes less about finding the money, and more about finding the right partners. It sounds like something you could do, doesn’t it?

The Princeton Institute for the Science and Technology of Materials

PRISM’s approach is a pragmatic one. The risk-tolerant money of the late 1990s and early 2000s is gone, thanks to the telecom bubble, the 2008 credit crunch, and the currently weak economic recovery.

“Instead of going around, trying to convince a venture capitalist to do something he’s never going to do"—that is, invest in an early-stage tech startup—"PRISM provides a framework for investors to understand up-and-coming technologies,” says Joseph Montemarano, the director for industrial enterprise at PRISM. The goal is to educate them, “so they feel comfortable investing in something six months to two years earlier than they otherwise would.”

Montemarano joined Princeton University in 1994 as an industrial liaison with the mission of proactively commercializing research discoveries. Soon the university was receiving funding from the New Jersey Commission on Science and Technology to work with local companies, and PRISM was formed. PRISM is responsible for materials research collaborations between Princeton faculty, companies, government labs, and other universities, including Texas A&M University, Rice University, the Johns Hopkins University, the City College of New York, University of Maryland, Baltimore, and St. Luke’s Hospital. It hosts the Mid-InfraRed Technologies for Health and the Environment

MIRTHE’s goal is to develop optical trace gas sensing systems at wavelengths from 3-20 µm using quantum cascade lasers, quartz-enhanced photo-acoustic spectroscopy, and other new technologies. Such optical trace gas sensing systems are potentially useful in industries from semiconductor manufacture to oil and gas extraction, as well as medicine and law enforcement.

Despite the technologies’ obvious applications, getting from lab development to product is tricky. The organic light-emitting device technology for Universal Display Corporation

“We were talking to researchers [in AT&Ts research and development division] about a technology; the financier and the lawyer went into a business unit and talked to them about a technology business,” Montemarano recalls.

That experience goaded Montemarano into expanding the mission of the investor focus group. Now the group works to educate not only investors about technology but also researchers about business. About two dozen venture capitalists and angel investors meet twice a year at events focused on a particular industry sector. Industry specialists discuss the opportunities and needs for technological solutions. Researchers discuss state-of-the-art technology and how it could address those needs. Investors discuss what makes a technology business an attractive investment. Everyone learns. Ralph Taylor-Smith and Mort Collins, both general partners at Battelle Ventures, chair the focus group. Taylor-Smith and Collins bridge the gap between the worlds of science and business, having each worked in research as well as venture capital.

As a researcher, “you know how science creates things. You don’t how it’s productized,” Collins says. In order to turn a technology into a technology business, “you need to have input from industry.” Over the years an entire ecosystem of companies, investors and entrepreneurs has developed that work with PRISM’s researchers to identify promising technologies and nurture them into businesses.

But how does a researcher without those resources get that kind of feedback? Collins and Taylor-Smith recommend attending industry events and chatting with business development people. “Every large company has business development people whose job it is to look over the horizon and find new markets and opportunities. Have a dialogue and talk about potential applications. You will find a ready and willing audience,” says Taylor-Smith.

Researchers who enjoy collaborating on a business but prefer to devote their work time to the lab may choose to license their technology to an entrepreneur, who pursues the business component. Montemarano emphasizes that, from Princeton’s point of view, this is a desirable outcome. His goal, he says, is not to push as many researchers as possible out of academia and into their own companies, but rather to keep them in the university, free to research the next generation of the technology.

But sometimes researchers do make the leap into business.

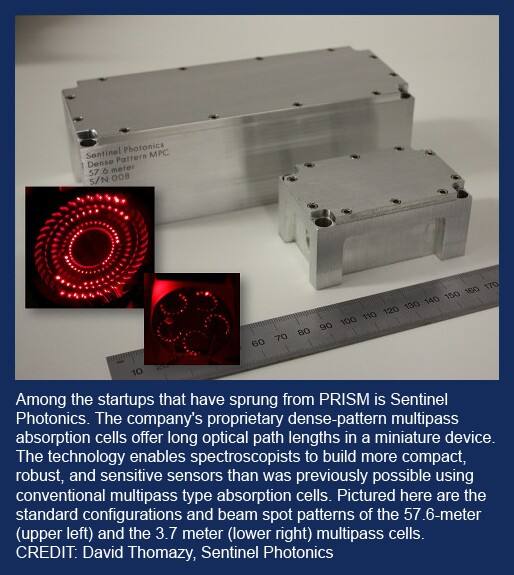

“In the back of my mind I knew I wanted to start a company, but I never pursued it,” says Stephen So, president of Sentinel Photonics

So had received mentoring from the investor focus group, and he and Thomazy knew they needed to prove out the technology before an investment capitalist would even look at it. Besides their own pockets, their early funding came from a Small Business Innovation Research

“Get a good team together, people you can work with without getting into huge fights. Because there will be disagreements!” he says. “And be as efficient as possible, because you will burn money.”

Montemarano is pleased with the successes that have sprung from the PRISM/MIRTHE business-research ecosystem. And he intends there to be many more. In some ways, the tough business climate for startups is a blessing. It forces potential businesses to consider both the technology and the market very carefully. And everyone in the investor focus group agrees that’s a good thing.

Kim Krieger is an independent science writer. She has reported on science policy from Capitol Hill, energy from the floor of the New York Mercantile Exchange, and physics innovation everywhere.