How dicarbon breaks apart

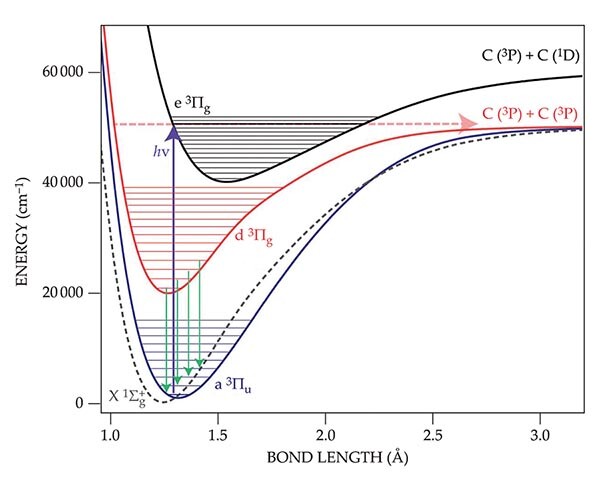

Like oxygen and nitrogen, dicarbon is a homonuclear diatomic molecule. But unlike its atmospheric counterparts, C2 is so reactive that it exists only in rarefied or highly energetic environments. It can be found in flames, comets, stars, and the diffuse interstellar medium. In its lowest triplet state, C2 announces its presence through the blue-green fluorescence of so-called Swan bands (green, d3Πg → a3Πu), shown here in the molecule’s energy-level diagram. In 1939, future Nobel laureate Gerhard Herzberg suggested that the excitation of C2‘s electrons into the e3Πg state by sunlight would result in the dissociation of the molecule. The suggestion would explain why a comet’s coma is often green, while its tail is not, as shown in the photograph of comet Lovejoy’s fluorescence. Sunlight first heats the comet’s ice and organic material to produce C2 molecules, only to break them apart before they can ever reach the tail.

Adapted from J. Borsovszky et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2113315118 (2021)

Eighty-two years later, researchers led by Timothy Schmidt

John Vermette

The energy-level diagram outlines the mechanism: After excitation from the ground state (purple arrow), the molecule makes a brief stop on the black manifold of e3Πg states, as predicted by Herzberg, before relaxing to the red manifold of d3Πg states. It’s on those d3 states that the two carbon atoms dissociate (red dashed horizontal arrow). From that mechanism, the researchers then used quantum chemical calculations to predict the lifetime of cometary C2 as 1.6 × 105 seconds, a value reassuringly consistent with astronomical observations. Part of what makes the investigation so difficult is that dicarbon is unstable. To break a newly made C2 bond, the molecule must absorb two photons. And during that absorption, C2 undergoes two forbidden spectroscopic transitions: spin conservation and the Born–Oppenheimer approximation. (J. Borsovszky et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2113315118, 2021