Fast x-ray scattering reveals water’s two liquid phases

Frozen water can exist in at least 18 different crystalline forms, depending on the temperature, pressure, and preparation conditions. For decades, researchers have investigated—and at times, fiercely disputed—whether supercooled liquid water also possesses distinct high- and low-density phases separated by a phase boundary.

On the theoretical side, the two-liquid hypothesis got a boost in 2018 when the leading model that argued against the liquid–liquid phase transition was found to contain a coding error

Now Stockholm University’s Anders Nilsson

Rather than cooling water from room temperature, the experimenters approached the no-man’s-land regime from below, by heating amorphous ice. Made by chilling water so quickly that it solidifies before it can crystallize, amorphous ice exists in high- and low-density forms that are thought to correspond

The newly liquefied water rapidly decompressed before refreezing into crystalline ice. The dynamics of that expansion, which the researchers probed with an x-ray pulse precisely timed to follow the IR pulse, would reveal water’s phase behavior in no-man’s-land.

K. H. Kim et al., Science 370, 978 (2020)

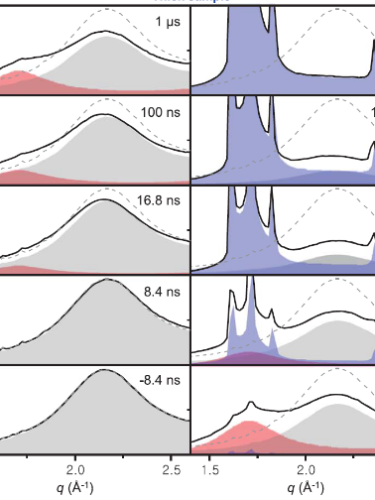

The results are shown in the figure. When the x-ray pulse followed the IR pulse by tens of nanoseconds or less, the x-ray scattering intensity (solid black lines) was dominated by a smooth distribution (gray) that corresponds to the high-density liquid. (Higher values of the momentum transfer q correspond to shorter particle separations.) For delays of tens of microseconds or more, the series of discrete peaks (purple) signaled the formation of crystalline solid ice.

But in between—for delays of a few microseconds—the x-ray signal showed a second smooth hump (pink), the hallmark of a distinct liquid phase of lower density. By showing that the liquid–liquid transition exists and is experimentally accessible, the work paves the way for further study of water’s unusual behavior. (K. H. Kim et al., Science 370, 978, 2020

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org