”Faked states” mimic quantum entanglement

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.1350

Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen argued in 1935 that quantum mechanics is not a complete theory, because a measurement on one system can influence the wavefunction of another in a way that’s incompatible with the light-speed limit on information propagation. 1 If that “spooky action at a distance” is to be avoided, there must be more to the reality of each system than its wavefunction describes. Quantum mechanics might be supplemented, for example, by a theory of hidden variables, so that the outcome of each measurement depends only on the local degrees of freedom.

Nearly 30 years later, John Bell showed that the issue is not merely philosophical: An experiment can be devised to distinguish quantum mechanics from any local hidden-variable theory.

2

(See the article by David Mermin in PHYSICS TODAY, April 1985, page 38

However, Bell tests are subject to several conditions, or loopholes. For example, to close the locality loophole, the experiment must be set up so that no light-speed propagation of information can influence the outcome. And to close the detection loophole, the measurements must be efficient enough to rule out the possibility that the observed events violate the Bell inequality but the entire ensemble does not. Bell tests in the lab give results consistent with quantum mechanics, 3 but no test has yet closed all the loopholes simultaneously. These days, the tests’ main practical use is not to erase doubts about the validity of quantum mechanics but as “entanglement witnesses” to verify the quantum nature of specific light sources.

Now, Vadim Makarov (Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim), Christian Kurtsiefer (National University of Singapore), and their colleagues at both institutions have shown that they can violate Bell’s inequalities in a system that manifestly lacks entanglement, if they ignore one loophole or another. 4 They use what they call faked states: classical pulses of light designed to trick the detectors into behaving as if they’re detecting single photons. The researchers point out that it’s unlikely that we’re all victims of a conspiracy to make it look like we’re observing quantum entanglement when we’re not, but that a loophole-free Bell test is still a desirable goal. And the same groups have done related work on a system in which deliberate deception is a serious issue: hacking the quantum key distribution of quantum cryptography systems.

Fooling photodiodes

The Bell test setup that the researchers endeavored to fool uses polarization-entangled pairs of photons. The two photons are sent in opposite directions through optical fibers to the receivers Alice and Bob, each of whom performs a polarization measurement in one of two bases. Alice chooses at random between basis A at 0° and basis A’ at 45°; Bob chooses between basis B at 22.5° and basis B’ at −22.5°. If the photons are perfectly entangled, Alice and Bob’s measurement results will be the same with probability cos2 (22.5°), or 85.3%, unless Alice chooses basis A’ and Bob chooses basis B’, in which case the results will be different with probability 85.3%.

One then computes the quantity S = EAB + EA’B + EAB’ − EA’B’ where E is the probability, for the bases given, that the measurement results are the same minus the probability that they’re different, disregarding any events for which either Alice or Bob failed to detect a photon. For any classical system, ∣S∣ ≤ 2; that’s Bell’s inequality. But for perfect entanglement, S = 2.83, which violates it.

Each receiver consists of a polarizing beamsplitter (PBS) and two avalanche photodiodes (APDs), which serve as single-photon detectors. In front of the PBS is a half-wave plate that can be rotated to change the measurement basis. Each APD is a semiconductor diode with a bias voltage applied in the reverse direction. The voltage is so high—above the diode’s breakdown voltage—that it could generate a current in the reverse direction all by itself, but for the lack of free charge carriers. An incoming photon remedies the situation by generating a free electron and a hole, which undergo avalanche multiplication to produce a macroscopic current. When the current becomes large enough, the detector registers a click, meaning that a photon has been detected. The device then lowers the bias voltage to cut off the current and raises it again to prepare the APD for the next photon’s arrival.

But when the APD is fed a sufficiently bright stream of photons (on the order of 100 µW, although much lower powers can also suffice), it never has a chance to recharge its applied voltage, and the detector registers no clicks: It is blinded. An even brighter pulse on top of that (on the order of 5 mW) can generate a large enough photocurrent to produce a click, without the benefit of avalanche multiplication.

So for their faked states, the researchers combine a continuous circularly polarized beam and a bright linearly polarized pulse. The circularly polarized light is equally divided between the two APDs, regardless of the position of the half-wave plate, and blinds them. The overlying bright pulse is polarized in the direction that the researchers want the receiver to detect.

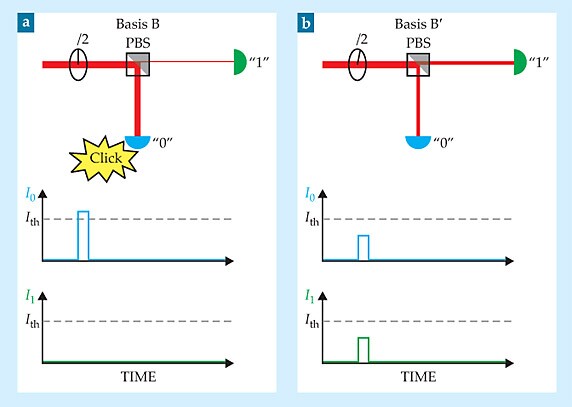

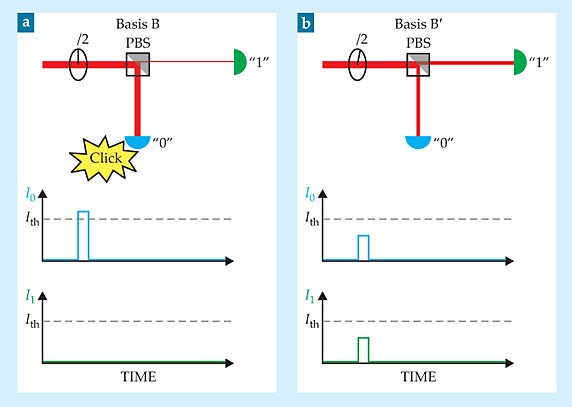

Figure 1 shows the response of Bob’s receiver to a faked state designed to produce a “0” in basis B. If Bob happened to choose basis B, the entire bright pulse is directed toward the 0 APD, where it generates a photocurrent large enough to produce a click. But if Bob chose basis B’, the pulse is divided between the APDs. Both APDs see a photocurrent pulse, but neither is sufficient to produce a click.

Figure 1. Faked states in a Bell test. The receiver consists of a polarizing beamsplitter (PBS), two single-photon detectors (“0” and “1”), and a half-wave plate (λ/2) that is rotated to choose between two measurement bases. The faked state consists of a circularly polarized beam—which blinds the detectors so that they’re sensitive not to single photons but to bright pulses—and a bright pulse that’s linearly polarized in the direction of the desired outcome in the desired basis. (a) When the correct basis is chosen, the bright pulse produces a photocurrent pulse in one detector that exceeds the threshold to produce a click. (b) When the wrong basis is chosen, both detectors see a photocurrent pulse, but neither exceeds the threshold.

By sending Alice and Bob each a sequence of faked states, the researchers can create any pattern of correlations they like. They can mimic the correlations of entangled photons, or even, if they want, create correlations that would seem to be impossible for any classical or quantum system. But Alice and Bob each detect just half of the faked states they receive, so the detection loophole is not closed. For Bell experiments using actual photons, detection efficiencies are typically much less than 50%. Those experiments rely on the assumption that the events detected constitute a fair sample of all events. That’s a reasonable assumption, but the faked-state experiment—in which states are designed to be undetectable if the wrong basis is chosen—shows how it can fail.

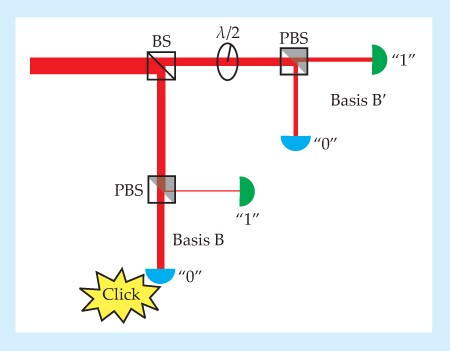

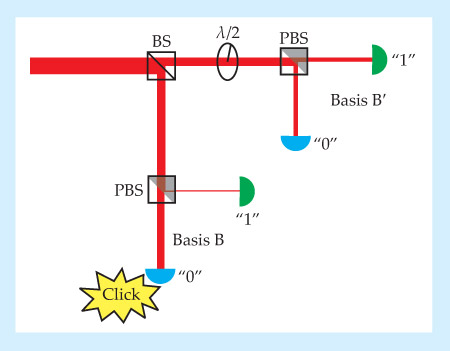

Figure 2 shows an alternate setup in which the detection loophole is closed but the locality loophole is not. Rather than controlling the measurement basis by rotating a half-wave plate, each receiver uses an ordinary beamsplitter (not a polarizing one) to direct the incoming photon to one of two polarization analyzers, one for each basis.

Figure 2. Passive basis choice using an ordinary beamsplitter (BS). A single photon would be detected in one basis or the other with equal probability. But a faked state can force a detection in the basis of choice.

When the incoming state really is a single photon, the beamsplitter works just as well as the rotating half-wave plate to ensure a random choice of basis. But with their faked states, the researchers can force the receiver to register a click in whichever basis they like: The circularly polarized beam is evenly divided among the four APDs and blinds them all, and the linearly polarized beam is designed to produce a click in the desired basis and no click in the other.

The beamsplitter setup fails to close the locality loophole because of the possibility that some classical parameter, propagating along with the photon, dictates the basis in which the photon is detected. The possibility may seem implausible with real photons, but it’s exactly what the faked states do.

Hacking cryptosystems

Quantum key distribution is similar in many respects to a Bell experiment: Polarization-entangled photons are sent to Alice and Bob, who measure them in randomly chosen bases. (Unlike in the Bell experiment, each receiver chooses from the same set of bases.) Alice and Bob then confer about which bases they used, discard all events for which they used different bases (or in which one of them failed to make a measurement), and they are left with identical sequences of zeroes and ones that only the two of them know.

In principle, the process is unhackable: Because it’s physically impossible to observe a quantum state and reliably regenerate the same state, any attempt to eavesdrop on the photon transmission should be instantly detectable. (See the Quick Study by Bill Wootters and Wojciech Zurek in PHYSICS TODAY, February 2009, page 76

References

1. A. Einstein, B. Podolsky, N. Rosen, Phys. Rev. 47, 777 (1935). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.47.777

2. J. S. Bell, Physics 1, 195 (1964).

3. A. Aspect, Nature 398, 189 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/18296

4. I. Gerhardt et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 170404 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.170404

5. I. Gerhardt et al., Nat. Commun. 2, 349 (2011); https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1348

L. Lydersen et al., Nat. Photonics 4, 686 (2010).https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2010.214

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org