Exporting coal: questions and uncertainty

DOI: 10.1063/PT.4.2406

Much of the current discussion regarding fossil fuels focuses on replacing them with sustainable alternatives and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. But the symposium at last month’s AAAS meeting on the impacts of building a new Gateway Pacific coal export terminal in Cherry Point, Washington, was notable in that it promoted a science-based dialogue on a different aspect of the same problem: dealing with the continued use of coal to generate electricity.

‘We forget that coal still dominates the world’s fuel growth,’ said Dan Kammen of University of California, Berkeley’s Renewable and Appropriate Energy Laboratory

The proposal

The proposed Gateway Pacific Terminal in Puget Sound would allow the US to ship 48 million metric tons of coal annually through Seattle. That’s enough to make a pile one half mile in diameter and ten feet taller than Seattle’s largest building, Columbia Center.

‘There already is a lot of shipping along Puget Sound and the Columbia River and there is ready access to the BNSF railway line,’ explained Donna Gerardi Riordan of science education consultancy DGR Strategies. Cherry Point’s naturally deep water would not require any dredging to accommodate massive vessels, and existing railway lines would transport coal from Wyoming’s mines to the port.

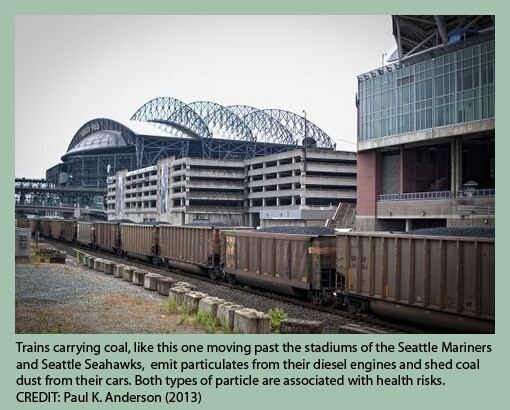

But even that seemingly low impact spells bad news for fragile ecosystems in the American West: environmental and health issues range from endangered species to fish stocks, potential for spills, fueling of vessels, and coal dust and diesel particulates along rail lines and at the port, to say nothing of global climate change.

‘How do we know what the impact of coal mined in Wyoming is when it is burned halfway around the world?’ asks Gerardi Riordan.

It remains to be seen whether the scope of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for Gateway Pacific will be limited to the exact physical site of the coal terminal, or expanded to a much larger area, including the coal mine itself. A draft statement in the coming months will specify the research and analysis needed to identify significant impacts and suggest how they might be mitigated.

Uncertainty in the wind

The EIS is open to comments from the public, and physicist Michael Riordan requested that the effects of winds on coal transport, and the resulting coal dust, be addressed.

‘I am overwhelmed by the level of uncertainty involved in trying to estimate just how much coal dust will be released by these operations, both into the atmosphere and into waters surrounding the coal terminals,’ he said. Bernoulli’s law implies that the force pushing the dust through the air goes as the square of the wind velocity.

But putting a number on wind velocity involves huge uncertainty: The average wind speed at Cherry Point is 10 mph, but winds often exceed 40 mph. Severe conditions will determine the amount of airborne coal dust. It is also necessary to study what happens in other coal transport facilities in order to learn how winds interact with various coal piles and transport mechanisms.

‘I don’t think anybody knows [wind effects] better than a factor of 10,’ adds Riordan. Extensive modelling efforts of the complex physical situation would help, but that takes time and money and Riordan doubts it will happen. He is trying to bring pressure to see that it does.

Unhealthy observations

At Washington State University, Melissa Ahern studies the health effects of coal production and burning on communities in Boone County, West Virginia. She aims to create a case study for exposure to air particulates from coal mining, processing, and transport.

‘Coal is not easily transported,’ adds Ahern. ‘Oil can be put in pipelines which have their own issues, but coal...is moved by truck and rail. That involves a different set of potential problems.’

The bituminous coal-rich Appalachian region is subjected to environmentally scarring mountaintop removal mining, which produces particulate sources from explosives, coal dust, and diesel exhaust from transportation. Levels of ultrafine particles are significantly higher in mountaintop removal samples compared to other studies in urban areas. Worryingly, the particles are small enough to cross blood-brain barrier and penetrate cell walls.

Groundwater tests reveal elevated sulfate, iron, manganese, and zinc levels; while soil is found to have elevated levels of xenobiotics (chemicals that are found in an organism yet are not expected to be present in it). Add to this the high level of birth defects in mountaintop removal counties and impaired lung function due to inhalation of coal dust, and the potential impact of Cherry Point port construction becomes enormous.

A report

The Alliance for Northwest Jobs and Exports

The happy ending?

‘The biggest coal company in America and the world want this to go through. That’s what we are fighting,’ says Gerardi Riordan.

But it’s not simply a case of environmentalists versus corporate America. It’s about citizens becoming aware of corporate decisions in local communities. Once the EIS is in place, research can pinpoint the most important issues, and contribute to unpacking specious arguments.