Experiment resolves long-standing iron-spectrum discrepancy

Ionized iron glows purple in this Chandra X-Ray Observatory image of the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A.

NASA/CXC/SAO

As the most abundant heavy element in the universe, iron is a key diagnostic for spectroscopic studies of the sky. In particular, x-ray astronomers rely on the emission lines of highly ionized states such as Fe XVII (or Fe16+) to understand properties of celestial plasmas. The emissions are the result of dynamic processes such as electron collisions, so researchers can use them to infer things like the temperature of electrons in the plasma.

But for more than 20 years, two strong lines from the ion’s 3d→2p transitions, dubbed 3C and 3D, have confounded researchers. Theoretical calculations asserted that the ratio of the intensities of 3C and 3D was high, whereas the ratio in laboratory experiments remained stubbornly low. The discrepancy has undermined Fe XVII’s reliability as a diagnostic.

“It cast a pall on how well we understood what we were doing spectroscopically,” says Nancy Brickhouse, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics|Harvard & Smithsonian and a member of AtomDB, a database of x-ray spectra. “You could have the temperature off by factors of two, three.” Inaccurate values for 3C:3D even led x-ray astronomers to change the way they viewed images from telescopes like the Chandra X-Ray Observatory and XMM-Newton, she says. For example, researchers sometimes had trouble distinguishing whether the fuzziness of images was due to a plasma’s opacity or its density.

A new laboratory measurement likely resolves the discrepancy. It pegs the 3C:3D ratio squarely at 3.51, close to theoretical results that center on 3.5. The finding

Fe XVII is called “neonlike” because, like neon, it has 10 electrons and filled orbitals, which allow the ion to be stable for a wide range of temperatures between about 2 million and 10 million Kelvin. Because of that stability, the Sun is brighter in Fe XVII than anywhere else in the x-ray spectrum. Fe XVII is also present in plasmas around active galactic nuclei; electrons or photons collide with iron ions, causing them to emit x rays.

The earliest measurements of the 3C:3D ratio were rough astrophysical estimates from the Sun, with values well below 3. By the 1990s, theorists were using simplified computer models to calculate 3C:3D, which yielded values around 4. At first, researchers attributed the discrepancy to resonance scattering—the spreading out of peaks in emission spectra, often due to the density of the source plasma. Resonance scattering in the Sun’s corona would have smoothed the 3C peak, suppressing the 3C:3D ratio.

“I think people still believed that this issue was not a big deal,” says Chintan Shah, an atomic physicist at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center who worked on the latest result.

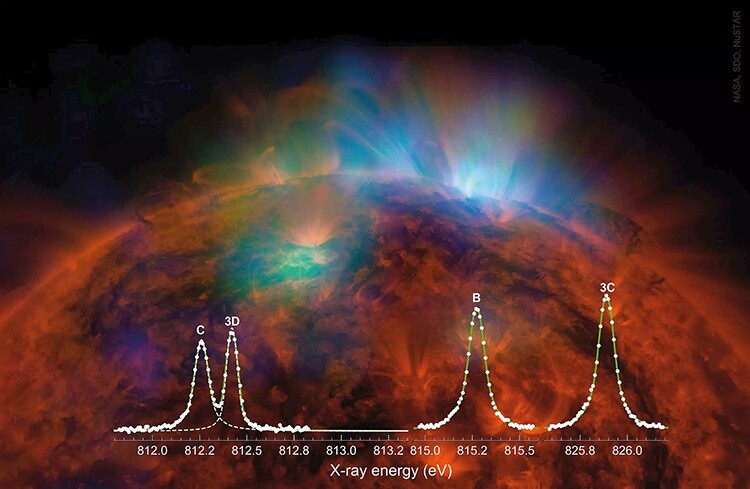

This view of the Sun overlays x-ray observations (green and blue) from the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array on an image by the Solar Dynamics Observatory. The most intense x-ray emission lines include 3C and 3D from Fe XVII and B and C from Fe XVI.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/GSFC

But in the early 2000s, electron beam ion trap (EBIT) experiments, in which large resonance scattering was impossible due to a low-density plasma, found 3C:3D values around 3. With x-ray astronomers eager to get the most out of observations from Chandra and XMM-Newton, which by then were in operation, concern about the discrepancy grew, Shah says. It wasn’t clear which value was correct.

A back-and-forth ensued. When a 2012 EBIT measurement made at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) in California reported a low value of 2.61, experimentalists claimed the theory was wrong. Theorists responded by performing more complex calculations, converging on a value around 3.5. They also pointed out an experimental design flaw: The LCLS’s x-ray pulses were too rapid and had spikes in intensity, which prevented ions from de-exciting between pulses and led to nonlinear effects.

In 2020 Shah and his colleagues improved on previous EBIT experiments by using a synchrotron source, PETRA III in Germany. The researchers increased their resolution tenfold, in part by using intensities a millionth as high as those at the LCLS, which gave the ions enough time to de-excite between pulses. Even so, the team measured

“The morale of the group was quite low, because we kept missing it,” says Steffen Kühn, an atomic physicist at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics who was involved with the latest research. “We decided we had to make a fundamental change.”

For the latest experiment, also at PETRA III, the group targeted the natural linewidths of 3C and 3D rather than simply the intensity ratio. The trouble is that 3C and 3D are very narrow lines, only a few meV wide, because linewidth is inversely proportional to lifetime. To distinguish the lines, they increased their resolution by a factor of 2.5. They also isolated the signal from the background, boosting it by a factor of about 1000, which allowed them to measure the “Lorentzian wings” of the line, a gentle slope that never quite goes to zero. With those improvements, the team found the 3C:3D ratio was 3.51, finally in agreement with theory.

For decades, observational and experimental efforts to determine the 3C:3D ratio of Fe XVII delivered values that were consistently lower than those predicted by theory.

Daniel Garisto; created with Flourish

“I think having this paper, we can say we’re probably doing better than we thought we were,” Brickhouse says. “There’ll be a lot more credibility to the spectroscopy.” She also praises Shah, Kühn, and their colleagues for keeping at it after their disappointing 2020 result. “I give them a lot of credit for persisting and really trying to think about how they could check and what else they could do experimentally.”

The timing couldn’t be better. In May NASA and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency plan to launch the X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission, a successor to the short-lived 2016 Hitomi mission, to observe the x-ray spectrum with unprecedented resolution.

Although the Fe XVII discrepancy may now be resolved, researchers predict it won’t be the end of x-ray emission tensions. Liyi Gu, an astrophysicist on the SPEX database, says the Fe XVII problem is representative of the uncertainty that exists in modeling x-ray spectra. “We’re coming into 10 percent, 20 percent uncertainties everywhere.”

Shah agrees. “You will see more discrepancies,” he says. “And that will open up more new directions of what to measure and where the experimental efforts are needed.”

Editor’s note: The author is related to the managing editor of Physical Review Letters, but they had no communications about the paper.