Europe’s particle-physics community weighs its next collider

DOI: 10.1063/pt.cjou.oiwu

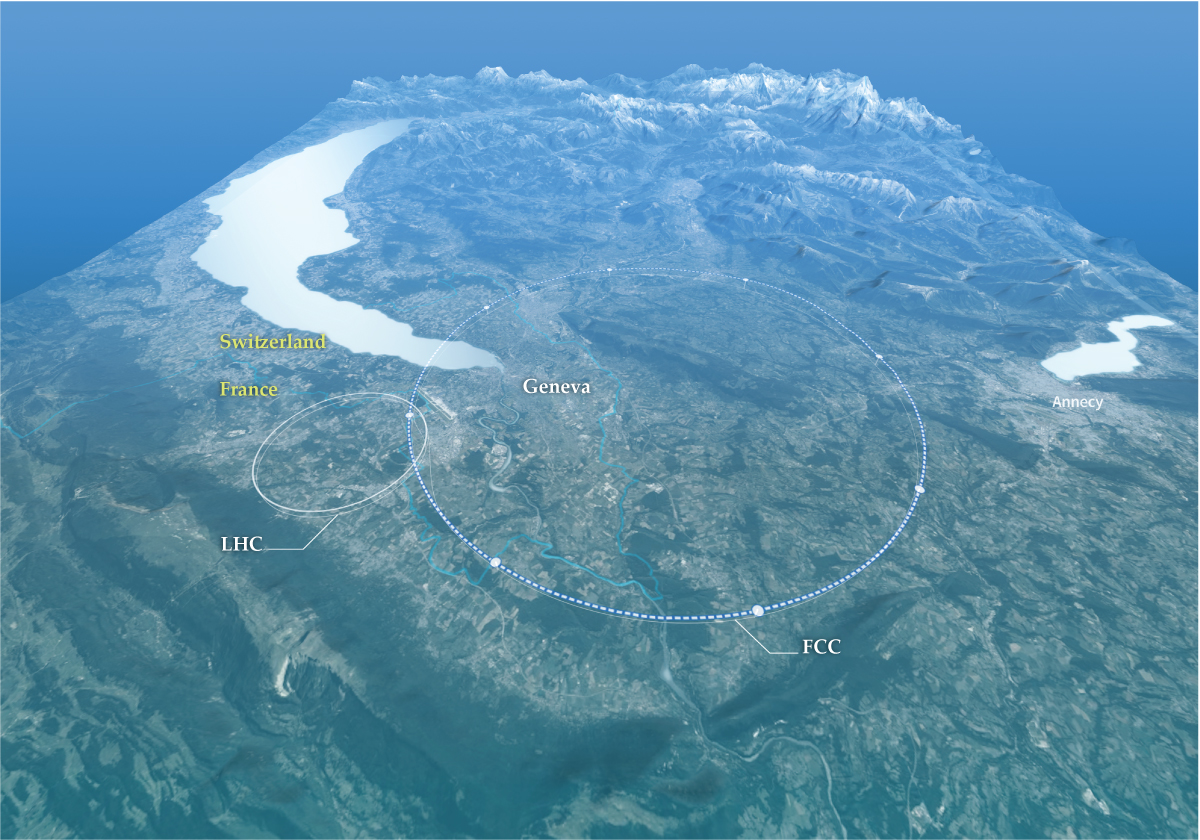

With a circumference of nearly 91 kilometers, the tunnel for the proposed Future Circular Collider (FCC) would be more than three times as long as the current tunnel for the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). (Image adapted with permission from CERN.)

After the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) shuts down, probably in the early 2040s, what comes next?

That question is the focus of Europe’s particle-physics community as it discusses the latest update to the European Strategy for Particle Physics (ESPP). The updates, organized by CERN every five to seven years, set a shared agenda for Europe’s particle physicists. Community input collected throughout the year will be compiled in December by a group of stakeholders

This particular update has high stakes: It could lead to CERN pursuing a new world-leading particle collider with a $10 billion–plus price tag.

Meet the Future Circular Collider

As part of the strategy process, CERN solicited proposals from the community. It received 263 submissions

Two of the submissions detail the leading contender for Europe’s next collider. First suggested in 2011, the Future Circular Collider (FCC) would occupy a 91-kilometer loop under France and Switzerland and would run in two stages.

The first stage, the FCC-ee

The FCC-ee submission to the ESPP includes a detailed feasibility study, which proposes that the machine begin construction in the 2030s, start operation in the 2040s, and run for 15 years. It would run at four energies for the detailed study of various particles, with the Higgs-focused phase colliding particles at 240 gigaelectron volts and producing around 3 million Higgs bosons. Researchers would be able to measure properties of the Higgs boson that have been predicted but are difficult or impossible to observe with the LHC, such as its decay into charm quarks, to check whether they match the predictions of the standard model of particle physics.

The next step, the FCC-hh

Both stages are expected to be expensive. The FCC-ee is projected to cost 15 billion Swiss francs (about $18 billion), of which 6 billion francs covers civil engineering, including the tunnel. That would require funding beyond CERN’s operating budget of around 1.4 billion Swiss francs per year; CERN would have to request funds from member countries. Even with the tunnel already dug, the FCC-hh would cost another 19 billion Swiss francs, mostly for the powerful 14 tesla magnets required to control its proton beams. Magnets that strong have yet to be built, but the report discusses several promising pathways where, in many cases, the necessary material properties have already been demonstrated.

Growing convergence

The FCC-ee isn’t the only Higgs factory that CERN could build. A linear collider would require less space than the FCC-ee and reach higher energies, but it would collide fewer particles and thus gather less data. One plan

Although a linear collider could be cheaper (with estimates around 8 billion Swiss francs), both plans have a later upgrade that brings the total cost to the same ballpark as the FCC-ee. With the cost savings not obvious and the disadvantage in data volume, physicists are turning away from linear options and toward the FCC. “My feeling is that for once, there is convergence,” says Troels Petersen, a member of the LHC’s ATLAS collaboration based at the University of Copenhagen.

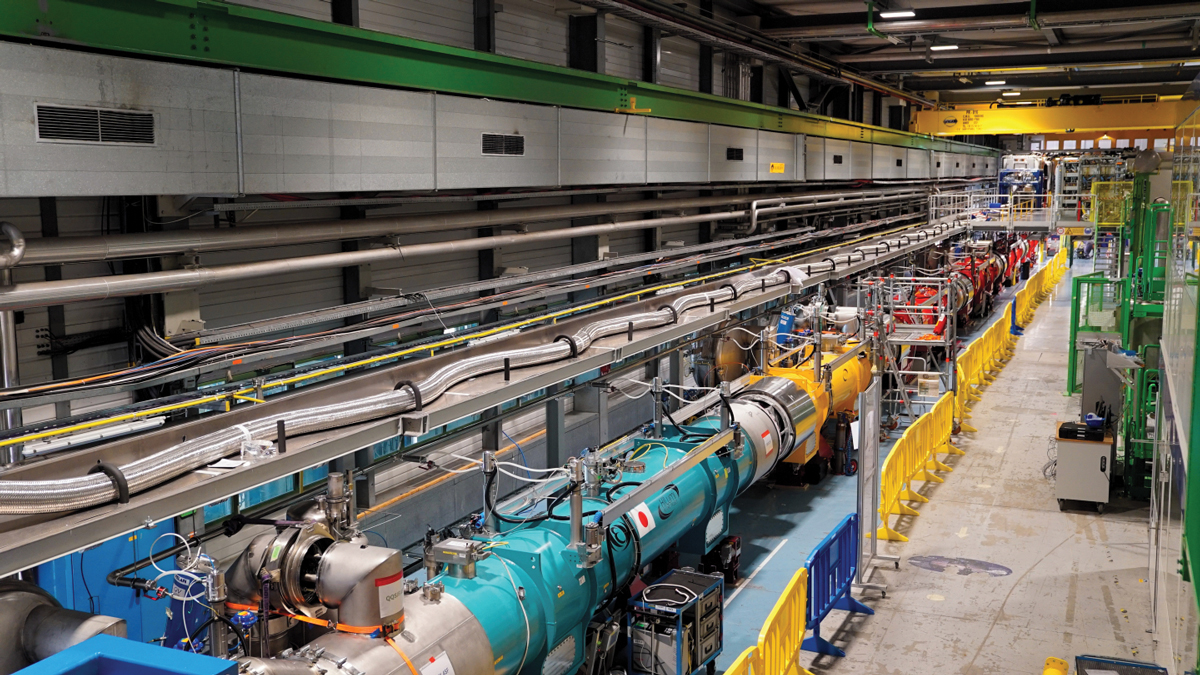

Using the High-Luminosity LHC test stand, CERN researchers will experiment with magnets and other components that should enable a substantial increase in the LHC’s particle collision rate. The High-Luminosity LHC program is scheduled to run from 2030 to 2041. (Photo by Florence Thompson/CERN.)

That convergence is clearest in the national inputs. Most countries state that the FCC is their preferred option, with the Swiss

A pivotal moment

What nearly everyone agrees on: The decision cannot be postponed. If CERN does not budget for the project, a new machine would not start until long after the LHC shuts down.

“If there’s a big gap, we run the risk of losing valuable expertise and top talent to industry,” says Thea Aarrestad, a researcher at ETH Zürich and a member of the Physics Preparatory Group’s detector instrumentation working group, which reviews proposals for particle detector technology for the ESPP.

The urgency doesn’t make the decision easier. At stake is a commitment not only to a Higgs factory but potentially to the FCC-hh as well: The FCC-hh may no longer be necessary if the FCC-ee shows no signs of new physics or if riskier technologies with higher potential, like a muon collider

If funding doesn’t materialize, CERN has backup proposals that involve reusing the 27-kilometer LHC tunnel for less

This article was originally published online on 27 June 2025.