Environmentally friendly, solar-powered deicing

Conventional deicing methods, as shown at Turin Airport in Italy, can be environmentally unfriendly.

Paolo Cerutti, CC BY 2.0

Surface ice can be frustrating or deadly. It can, for example, halve the efficiency of wind turbines, cause power lines to sag or break, and endanger the safety of airplane passengers. The ice can be removed by mechanical methods, such as hammering, but those cost energy. Chemical approaches use energy efficiently but often harm the environment. Materials scientists have designed hydrophobic surfaces that inhibit ice formation, but on humid days, ice can nonetheless clog surface structures. Now MIT’s Kripa Varanasi

The top layer is cermet, a ceramic–metal composite that absorbs solar energy efficiently but does not radiate it away. In practice, the cermet is unlikely to be uniformly illuminated—for example, it might be partly shaded. And since the material does not transmit energy well in the planar directions, the MIT team placed a thermally conductive layer of aluminum below the cermet to distribute the energy uniformly across the laminate. The bottommost layer of insulating foam keeps the heat from the Sun near the cermet rather than allowing it to penetrate into the substrate.

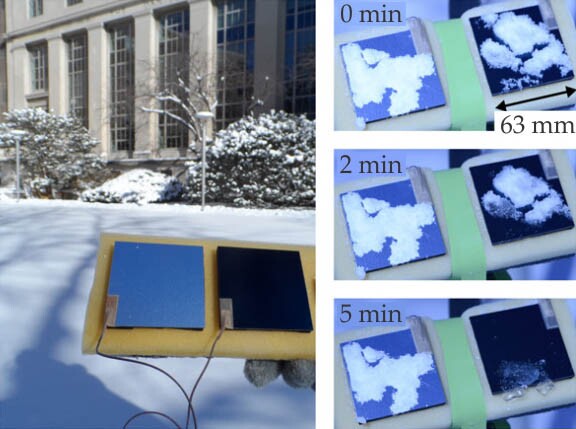

MIT laminate and aluminum sheet in action, courtesy of S. Dash, J. de Ruiter, and K. K. Varanasi.

The left panel of the figure shows the trilayered laminate (black square) and an aluminum sheet (blue square) on a cold (−3.5 °C), windy day at MIT. As the right panel shows, snow placed on the laminate melted and slid off within about five minutes, while the aluminum remained well covered. The colder and windier the day, the more time is needed for the laminate to deice. Under harsh conditions, natural sunlight may not provide enough energy for effective deicing. But the MIT laminate can remain ice free, at an energy cost, if the Sun is supplemented with an artificial light source, such as LEDs. (S. Dash, J. de Ruiter, K. K. Varanasi, Sci. Adv. 4, eaat0127, 2018