Engineering the energy levels in quantum dots leads to optical gain

DOI: 10.1063/1.2761788

Quantum dots make nearly ideal photonic devices. And colloidal chemistry can make nearly ideal quantum dots. Measuring some 1–6 nm across, such QDs are semiconductor crystals in which the potential-energy barriers at the dot’s boundaries strongly confine the electron wavefunctions in three dimensions. Owing to that confinement, a QD’s electronic response to a photon is much like that of an atom, producing a discrete energy spectrum that arises from the excitation of electron–hole pairs. The electron and hole that make up the pair, called an exciton, attract each other electrostatically and can recombine to create a photon extremely efficiently, a property that makes the dots strong light emitters.

What’s more, the wavelength of that light emission can be tuned over a wide range simply by tailoring the size of QDs grown in solution. And because such QDs can be chemically manipulated like large molecules, they can be painted onto surfaces, incorporated into polymer or glass matrices, and placed in a variety of microcavities, waveguides, or optical fibers.

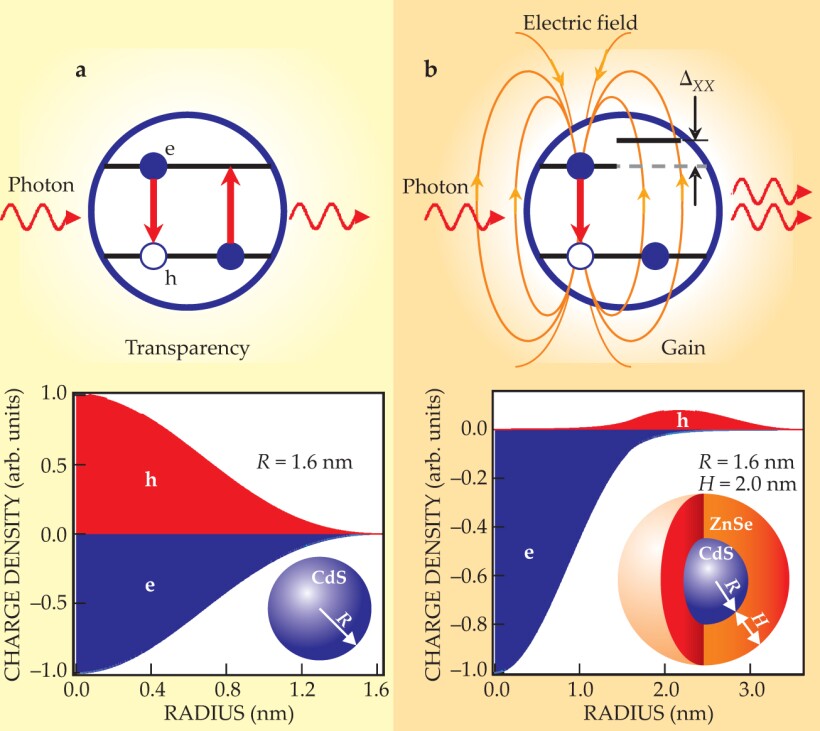

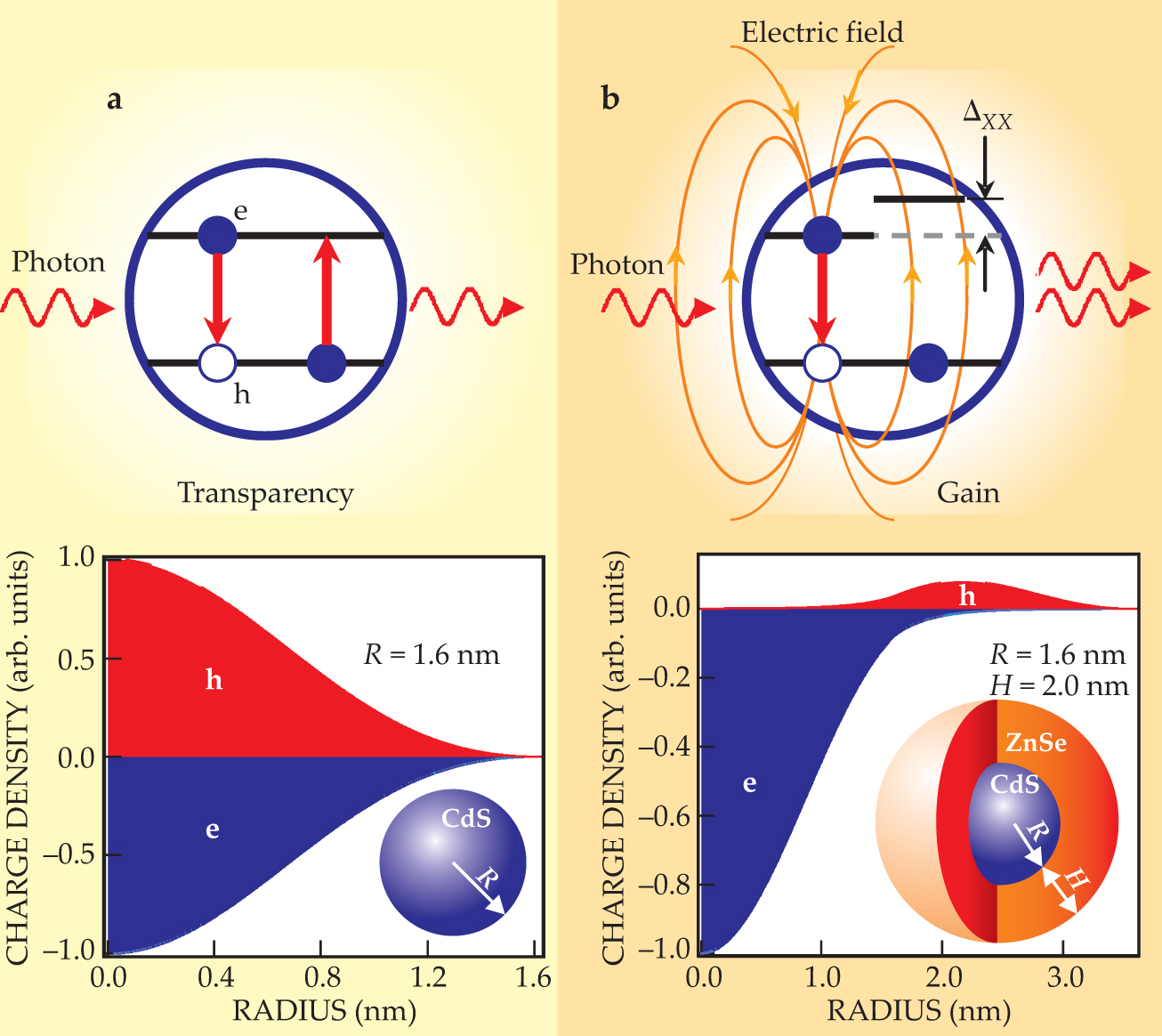

Despite nearly 20 years of effort, however, no practical optical amplifier or laser has emerged from work on colloidal nanocrystals. The problem lies in the fact that the energy levels associated with their light emission are nearly degenerate. That is, the energy required to excite one electron is about the same as that required to excite a second one to form a biexciton. The stimulated emission of a photon when a conduction-band electron recombines with its valence-band hole is then balanced by the photon’s reabsorption by an electron remaining in the valence band (see figure 1(a)). As in other lasing media, achieving optical gain—more photons out than in—in QDs requires that the number of electrons in the excited state exceed that in the ground state. Population inversion, therefore, occurs only if the number of excitons per QD is, on average, greater than one.

Figure 1. Single-exciton gain. (a) The light-emitting transition in conventional, homogeneous quantum dots can be described in terms of a two-level system in which each QD contains two electrons. The photon created from the stimulated recombination of an electron–hole pair, or exciton, is about as likely to be reabsorbed by the other electron in the dot to form a second exciton (loss) as it is to pass unabsorbed (gain). The net effect is transparency. The degeneracy in transition energies of states with either one or two excitons arises from the almost identical spatial distributions of electron (e) and hole (h) wavefunctions, as illustrated in the charge-density plot. The charge densities nearly cancel, and the exciton–exciton interaction energy is small. (b) Preparing QDs as core–shell structures made of cadmium sulfide and zinc selenide physically separates the electron and hole components of each exciton. The localization of each component breaks the degeneracy by an amount ΔXX, the Coulombic repulsion between like charges. The shift in energy required to excite a second electron can be thought of as a manifestation of the Stark effect: The electric field from one exciton changes the energy required to excite the second one.

(Adapted from ref. 2.)

Perversely, although biexciton states set the stage for optical gain, they severely hamper achieving it. Confined in the tiny volume of the same QD, the two excitons interact strongly enough that one annihilates the other in a process known as Auger recombination. In that process, the energy of one exciton is transferred to the electron or hole of the other. The highly excited electron–hole pair then relaxes to the ground state through the emission of lattice phonons rather than a photon, typically within 100 picoseconds, and destroys the population inversion.

In 2000 Victor Klimov (Los Alamos National Laboratory), Moungi Bawendi (MIT), and their colleagues realized that although the competition between radiative and nonradiative decay complicates the development of stimulated emission in strongly confined QDs, it doesn’t inherently prevent it. 1 One way to ameliorate the problem is to chemically passivate the dots, which reduces absorption losses such as the trapping of electrons and holes at surface defect sites. And by packing the dots closely together, the team could prompt them to emit light and collectively stimulate each other quickly enough to outpace Auger recombination and sustain population inversion. Even so, achieving optical gain still required optical pumping from intense and impractically short laser pulses.

Seven years later, Klimov and his Los Alamos colleagues now offer a more radical approach: Engineer the QD structure to amplify light using purely single-exciton states, which avoid Auger effects entirely. 2 To pull that off, the Los Alamos group chemically synthesized QDs that consist of a cadmium sulfide core coated with a zinc selenide shell.

Shell game

Heterostructures are, of course, not new. The University of Chicago’s Philippe Guyot-Sionnest and Margaret Hines (now at Evident Technologies) found in 1996 that coating one semiconductor with another, typically with a larger bandgap, passivates the surface of a QD more effectively than molecular ligands alone can. But the core–shell structure, it turns out, can also be used to alter the energetics of electrons and holes at the interface of the two materials.

Whereas in a conventional, homogeneous QD, the electrons and holes are delocalized over the entire volume, the valence- and conduction-band levels of CdS and ZnSe tend to separate the positive and negative charges of each exciton created by a photon. Electrons get driven into the core and holes into the shell, an effect that can produce large local charge densities (see figure

The advantage of the approach is that localizing the electrons and holes in different parts of the QD breaks the degeneracy between single-exciton and biexciton energy levels. The imbalance arises from Coulombic repulsion between like charges. Solving the Schrödinger equation for the system, Klimov and company calculated that the repulsive energies can be engineered to be as high as 100 meV, comparable to the QD emission linewidth due to variations in dot sizes.

The challenge for chemist Sergei Ivanov was to minimize the size of the CdS core—the greater confinement increases repulsion energies—yet still grow a thick shell. As the shell’s thickness increases, so does the separation between the electron and its companion hole, which weakens their attractive bond—again increasing the net Coulombic repulsion. To optimize the growth conditions, Ivanov created an alloy of the semiconductors at the core–shell interface by adding a little extra Cd into the mixture of Zn and Se precursors during the synthesis. The thin buffer layer of ZnCdSe at the interface cures the lattice mismatch between CdS and ZnSe and removes some of the strain and defects that otherwise limit the thickness and degrade the emission quantum yields.

Such custom-designed QDs alter what’s required to achieve optical gain. Because exciting the biexciton state requires a higher photon energy than a single exciton emits, biexciton absorption can be completely eliminated. If the pump fluence—that is, incident energy density—is low enough to populate QDs with only single excitons, stimulated emission from those states competes only with absorption from unexcited nanocrystals. In that case only two-thirds of the core–shell QDs require an exciton to reach gain threshold, and the remaining one-third require none at all.

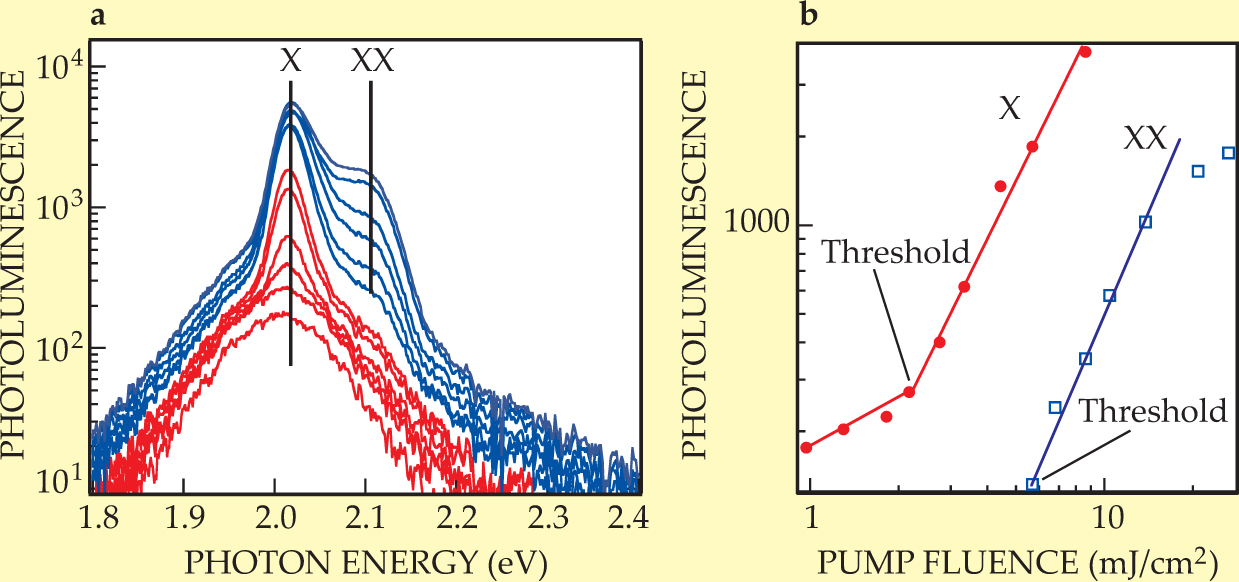

To quantify the relative advantage that operating in this single-exciton regime provides, the researchers monitored changes in the photoluminescence signal recorded from their core–shell QDs as a function of the pumping fluence from a femtosecond laser (see figure 2). The emergence of the narrow peaks on top of a broad fluorescence signal marks an evolution from incoherent fluorescence to coherent, amplified spontaneous emission at a threshold pumping fluence about three times lower than required using biexcitons.

Figure 2. Optical gain in core–shell quantum dots. (a) Monitoring the photoluminescence in response to gradual increases in the pumping energy of ultra-short laser pulses reveals the evolution from an incoherent fluorescence signal to a narrow, coherent peak due to amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) from single excitons (X). Exciton–exciton repulsion shifts the emission from biexciton states (XX) to higher energy. If pumped intensely enough, those states also demonstrate amplified emission (blue curves). (b) The threshold pump fluence required to generate ASE from single excitons is significantly below the threshold for biexcitons.

(Adapted from ref. 2.)

A more impressive advantage of the core–shell QDs, according to the University of Rochester’s Todd Krauss, is the long intrinsic lifetime of the single-exciton excited states, which can be more than 100 ns thanks to the weak electron–hole overlap. 3 Compare that with the 50-ps decay time typical for the multiexciton states of conventional QDs. As the ratio of threshold fluence and optical-gain lifetime, the pump-intensity threshold for lasing can therefore be orders of magnitude lower in core–shell QDs.

That fundamental difference, argues Klimov, clears the way for incorporating QDs into devices that rely on cheap, low-intensity, continuous-wave lasers—rather than expensive, ultrafast ones—to stimulate emission. Although it may yet take work to improve quantum yields and reduce scattering and absorption losses, the next step may be as simple as placing the dots in a resonant cavity to create a laser.

References

1. V. I. Klimov, A. A. Mikhailovsky, S. Xu, A. Malko, J. A. Hollingsworth, C. A. Leatherdale, H. -J. Eisler, M. G. Bawendi, Science 290, 314 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5490.314

2. V. I. Klimov, S. A. Ivanov, J. Nanda, M. Achermann, I. Bezel, J. A. McGuire, A. Piryatinski, Nature 447, 441 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05839

3. D. Oron, M. Kazes, U. Banin, Phys. Rev. B 75, 035330 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.75.035330