Electron Diffraction by Light, Envisioned 70 Years Ago, Is Observed at Last

DOI: 10.1063/1.1457252

Louis de Broglie’s 1923 proposal that particles could display wave behavior paved the way to modern quantum mechanics. Within five years, Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer in the US, and George Thomson in Scotland, confirmed de Broglie’s proposal by diffracting electrons off crystals. In 1933, Peter Kapitza and Paul Dirac proposed that a grating of standing waves of light could also diffract electrons: The diffraction peak separation would be proportional to the de Broglie wavelength of the electrons and inversely proportional to the wavelength of the light making the standing waves.

Kapitza–Dirac diffraction does not change the electron’s energy. This diffraction contrasts with the more familiar Compton scattering, in which an electron gains energy by interacting with a single photon. The diffraction predicted by Kapitza and Dirac arises through electrons interacting, by virtual absorption and stimulated emission, with an even number of photons.

The interaction is sufficiently weak that it could not be tested with the technology available in 1933: One needs pulsed lasers to get the requisite light intensity. In 1968, Lawrence Bartell and coworkers successfully scattered free electrons off standing light waves, and 20 years later, while at Bell Labs, Philip Bucksbaum and colleagues studied the scattering in detail. 1 Until recently, however, no one had observed the coherent diffraction peaks that characterize the Kapitza–Dirac effect.

Now, at last, Herman Batelaan, Daniel Freimund, and Kayvan Aflatooni, working at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, have observed coherent diffraction. 2 “This has been a long time coming,” commented David Pritchard of MIT, who led a team that observed a similar diffraction of neutral sodium atoms in the mid-1980s. 3 “And it’s really nice to see a definitive result.”

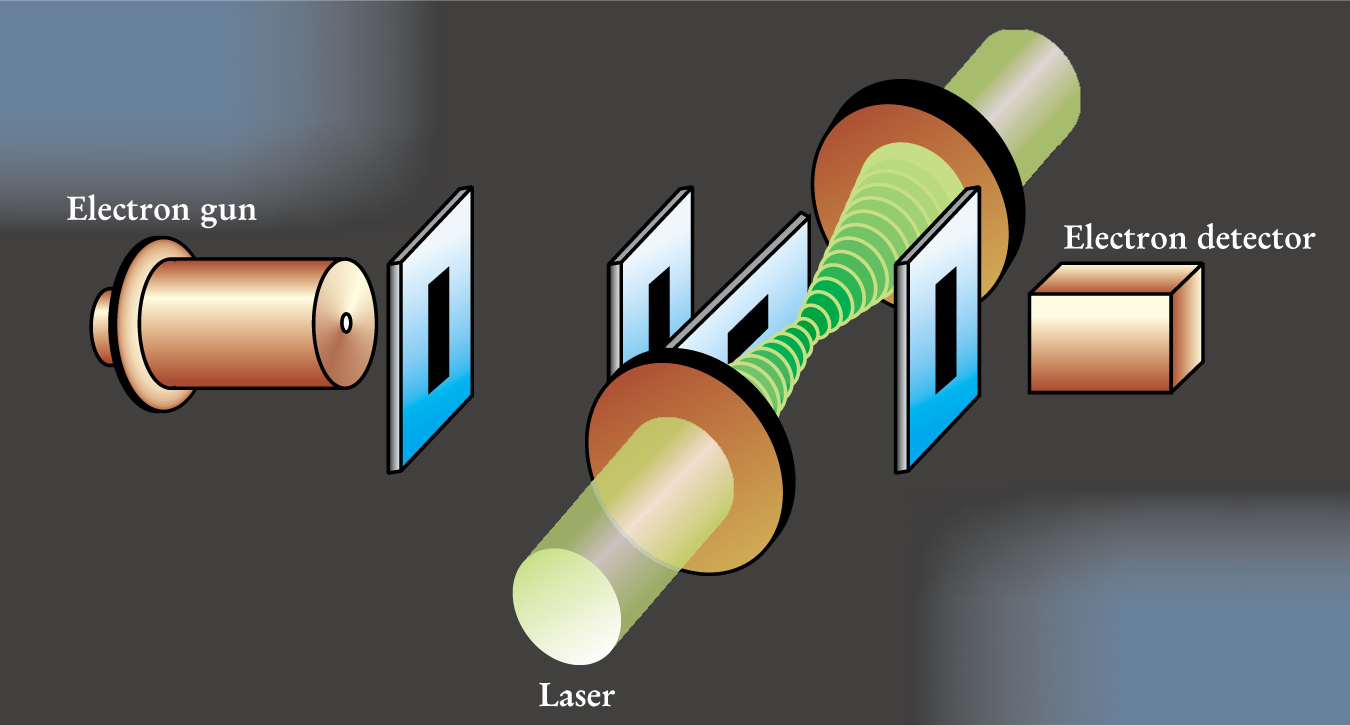

The heart of the Nebraska group’s experimental setup is shown in figure 1. After a pulsed laser beam is split, the resulting two beams are redirected so that they approach a pair of lenses from opposite directions. The lenses focus the counter-propagating pulses to a diameter of 125 μm. The total path lengths of the beams differ by no more than 1 mm, significantly less than the 5-mm coherence length of the laser, so that the light beams superpose to create a standing wave.

Figure 1. Experimental design to observe the Kapitza–Dirac effect. Counter-propagating laser beams combine to give a standing wave (green). Three slits focus the approaching electron beam. A fourth slit, downline from the interaction region, defines the detection direction.

(Adapted from ref. 2.)

The electron beam passes through three slits before encountering the standing wave. Two vertical slits yield a beam whose full width at half-maximum is 25 μm, while the third slit, a horizontal one, cuts the height of the beam down to that of the laser beam focus. The directions in which electrons emerge from the interaction region are measured with the help of a movable slit that is downstream from the laser. In any given trial, the position of the final slit is fixed, but over the course of several trials, the slit position is moved; electrons that pass through it are counted by the electron detector.

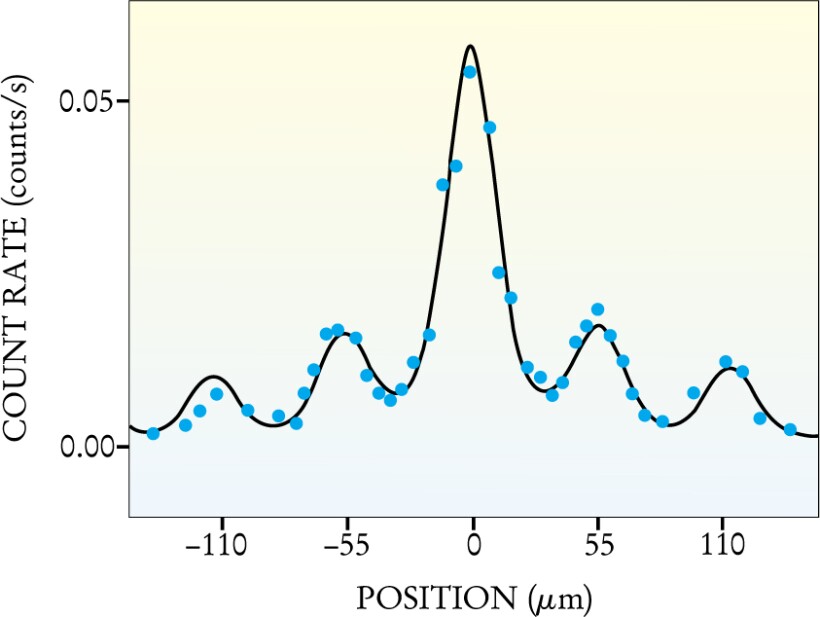

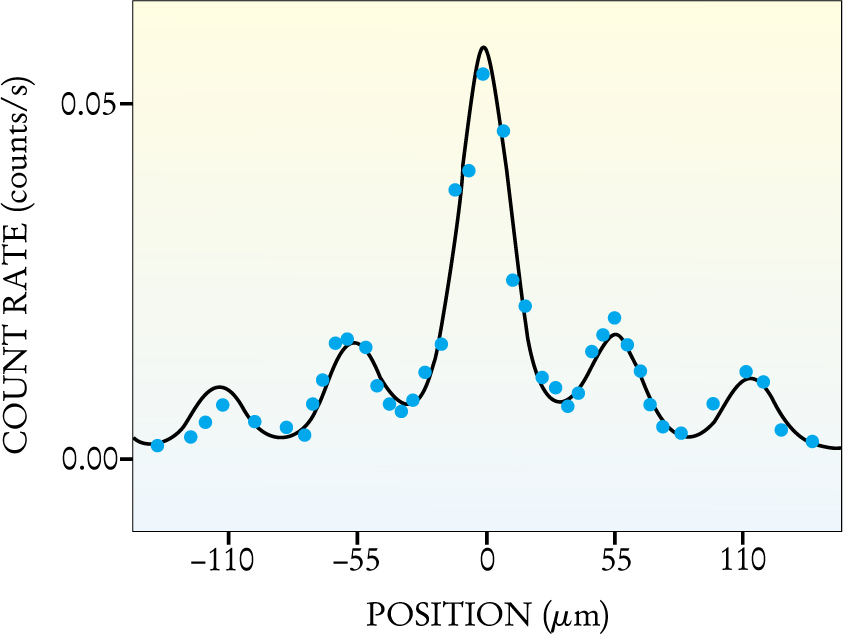

Figure 2 shows the experimental result, a series of diffraction peaks separated by 55 μm—just as one would expect, given the experimental parameters. The heights of the peaks are also in good agreement with theory, although the electron intensities are difficult to calculate. That’s because some electrons pass through hot spots in the focus of the laser beam, while others do not. Batelaan and company solved the Schrödinger equation numerically to obtain the theoretical curve indicated in the figure. The experimental data show a slight asymmetry, which the Batelaan group attributes to an electron beam that was not quite perpendicular to the laser beam. The asymmetry also appears in the numerical solution, which included the electron beam’s approach angle as an adjustable parameter.

Figure 2. Diffraction pattern of electrons by a standing light wave, giving well-defined peaks. The dependence of electron detection rate (blue dots) on detector position is in good agreement with a numerical calculation (black curve). The width of the diffraction peaks reflects the 25-μm width of the incoming electron beam.

(Adapted from ref. 2.)

What took so long?

A key reason the Kapitza–Dirac effect was so difficult to verify experimentally is the weak interaction of free electrons with the electromagnetic field of light. One needs the intense light of pulsed lasers to have any chance to see the effect.

The Nebraska group’s laser deposited 0.2 J in each of its 10-ns bursts. Although lasers can readily create pulses whose durations are shorter than 10 ns, the Batelaan group chose a more relaxed pulse length to increase the chance that the laser would be on when electrons crossed the interaction region, while still giving a high enough intensity for electrons and photons to interact.

In addition to being intense, the laser has to be well focused, a point emphasized in 1974 by Mikhail Fedorov of Moscow’s General Physics Institute. 4 If electrons take too long to cross the light beam, diffraction cannot be observed unless the electron beam is collimated beyond what is experimentally possible. Batelaan noted that increasing the width of the laser beam in his simulations caused the Kapitza–Dirac effect to disappear.

The electron beam must also be well focused so that the diffraction peaks can be resolved. The Nebraska group experimented with beam-defining slits of various sizes and materials before deciding that 10-μm-wide, acid-treated molybdenum slits worked best. In intermediate trials, 5-μm-wide slits introduced lensing effects that reduced the quality of the emerging electron beam. The experimenters admit they don’t fully understand the physics behind either the lensing effects or the superior performance of the acid-treated Mo slits.

There is precedent for the Batelaan group’s work. Pritchard’s work with sodium atoms, done in collaboration with Phillip Gould (University of Connecticut) and George Ruff (Bates College), used a continuous laser whose photon energy was near one of sodium’s atomic transitions. The near resonance of the laser light greatly enhanced the strength of the interaction between the atoms and light: The cross section in the MIT experiment was more than a billion times greater than that for electron-light interaction.

Bucksbaum (now at the University of Michigan), Douglas Schumacher (Ohio State University), and Mark Bashkansky (Naval Research Laboratory) studied in detail the scattering of electrons off laser light. 1 Working at Bell Labs, they used lasers a good 100–1000 times more intense than Batelaan’s, having a pulse width of about 0.1 ns. Such short pulses are not amenable to interaction with electrons in a beam. Rather, Bucksbaum and company used their lasers to ionize a rare gas, creating electrons in the laser focus; they reported seeing broad scattering peaks. The scattering observed by Bucksbaum’s group can be explained with a classical picture in which electrons are jostled about the oscillating potential associated with the standing electromagnetic wave before they are ejected from the interaction region.

Bucksbaum and company were unable to resolve single quantum-scattering features. The maximum of their electron-intensity distribution corresponded to scattered electrons absorbing the momentum carried by about 1000 laser photons, reflecting the enormous intensity of their lasers. The width of the peaks corresponded to about 100 photons’ worth of transferred momentum. The resolution of individual peaks, reflecting the interaction of electrons with small numbers of photons, had to wait another 13 years for the Batelaan group’s experiment.

A new regime

A number of potential applications exist for light gratings that can diffract electrons in a controlled way. Standing-wave light gratings, for example, could be used to explore features of quantum chaos. Mark Raizen (University of Texas) and coworkers diffracted neutral atoms with a light grating that was allowed to oscillate. 5 They observed certain predicted irregularities—signatures of quantum chaos—in the diffraction pattern when the grating was shaken in just the right way. That study may be extendable to electrons, whose charge allows additional interactions to be thrown into the mix.

A light grating, suggests Batelaan, could be a key component in a device that can separate electrons by spin. In the Batelaan and Bucksbaum experiments, scattering electrons interacted with an even number of photons. To satisfy angular-momentum conservation, then, the spin orientations of the incoming and diffracted spin-

Light gratings split electron beams coherently, and it may be possible to use them as splitting, bending, and recombining elements for an electron interferometer. Electron interferometers are not new, but the interferometers currently being used split electron beams of higher energies than those used by the Nebraska group. The lower energies allowed by light gratings would provide physicists with greater sensitivity to a variety of interactions, such as electron-atom forward scattering or the interactions of electrons with metallic surfaces.

The applications just described may not come to fruition. The experimental parameters that yield clean electron diffraction patterns are not suited to studying quantum chaos with electrons, and it remains to be seen if, for instance, relaxing the focus of the electron beam will allow for interesting studies. According to Batelaan, the spin separator he imagines may require prohibitively high laser intensities. But Mark Kasevich of Yale University notes that no one can predict how the field of quantum optics will evolve: Perhaps light gratings will see applications in quantum devices or in quantum computing. “We’re weaving some kind of quilt,” he explains, “and it’s hard to know where the connections are going to be made in even five years. Bringing the energy down for the coherent optics is pushing things to a new regime.”

References

1. P. H. Bucksbaum, D. W. Schumacher, M. Bashkansky, Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 1182 (1988).https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.61.1182

2. D. L. Freimund, K. Aflatooni, H. Batelaan, Nature 413, 142 (2001).https://doi.org/10.1038/35093065

3. P. L. Gould, G. E. Ruff, D. E. Pritchard, Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 827 (1986).https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.56.827

4. M. V. Fedorov, Opt. Commun. 12, 205 (1974).https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4018(74)90392-7

5. D. A. Steck, V. Milner, W. H. Oskay, M. G. Raizen, Phys. Rev. E 62, 3461 (2000).https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.62.3461