EGU 2011: The slippery slope of alpine glaciers, permafrost, and newly formed lakes

DOI: 10.1063/PT.4.0316

On the morning of 11 April 2010, the residents of Carhuaz, Peru, received a chilling reminder that warming effects are at work in the high mountains. Far above the town on the southwest slope of Nevado Hualcan (6104 m), an avalanche of rock and ice tumbled from hanging ice glaciers into a lake known as Laguna 513.

The impact caused the entire lake volume to oscillate in a so-called push-wave. After crossing the lake, the 25-meter-high wave spilled over its natural dam, sending a cascade of water and debris down the slope toward Carhuaz. The damage was severe, but no one was killed.

‘We know very little about the physical processes that started [the Nevado Hualcan avalanche],’ said Wilfried Haeberli of the University of Zürich’s geography department

At the general assembly of the European Geosciences Union, which was held earlier this month in Vienna, Haeberli was among several experts who spoke about climate change in alpine regions.

John Clague, a quaternary geologist and geomorphologist at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia, cited the thinning and retreat of glaciers as the most studied climatically-induced change in the alpine environment. According to models developed for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the areal extent of glaciers in many mountain ranges has shrunk by 20–30% since the late 1800s. By 2050, the European Alps’ glacial area is forecast to shrink by another 20–50%.

Clague pointed out that rock slopes that have been steepened by glacial erosion can break apart in avalanches once the glaciers that buttressed them retreat. But glaciers aren’t the only glue that holds the mountains together, and rock avalanches aren’t the only effect of retreating glaciers.

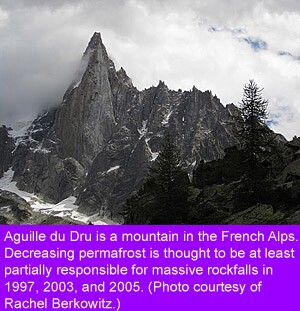

Warming permafrost is considered by Haeberli to have played a role in the Nevado Hualcan avalanche. Defined as soil at or below 0°C, permafrost can form if the mean annual air temperature is around −3°C. Thermal conduction and advection can warm bedrock enough to thaw permafrost. ‘Permafrost is involved in recent rockfalls on Monte Rosa [in the Swiss Alps],’ said Clague, but its effect is difficult to ‘untangle from glacial release of rockfall.’

Thawing permafrost not only reduces the support structure of rock that had been effectively frozen in place but, once thawed, leads to standing water within the rock formation. The freeze–thaw cycle of this standing water from the surface down elevates the pressure on water deeper in the rock, which, when it occurs on a repeated basis, weakens the rock.

‘The distribution of alpine permafrost is very patchy and is not controlled by latitude,’ noted Clague, adding that the topography and type of bedrock on which permafrost forms is hugely complicated. Sina Schneider, a PhD student at the University of Fribourg’s geography department

Schneider’s sample site is a 1-km2 section of slope in the Murtel-Corvatsch area, Upper Engadin, Switzerland. Ten boreholes are drilled 6 m deep in subsurface materials including rock glaciers, scree, and coarse- to fine-grained bedrock. All are subject to the same climate and atmospheric conditions, and are drilled at the same exposition and slope angle. ‘Previous studies looked at boreholes that were [geographically] far apart,’ Schneider explained. Any changes in her study ‘will not be due to microclimates. It must be the influence of the subsurface [materials.]’

Temperature and ice content in the boreholes have been logged twice daily for eight years. A simple thermistor measures the temperature, while ice content is calculated based on the resistivity and velocity of artificially generated pressure waves. The subsurface temperatures and calculated thermal diffusivities (ratio of conductivity to heat capacity) do indeed depend on the material: Subsurface temperature of the rock glacier is strongly influenced by its ice content, as ice-rich material has more efficient heat transfer due to its high temperature gradient. The bedrock site changes temperature more rapidly than the rock glacier site, and displays efficient heat transfer due to high conductivity. Fine-grained bedrock exhibits the largest cumulative temperature change.

‘You need a long time scale, 20 years at least, if you want to use permafrost as a climate indicator,’ Schneider added. ‘And deeper boreholes to have a stable signal.’

Not only do subsurface-dependent permafrost and retreating glaciers lead to unstable slopes that can cause avalanches like the one into Laguna 513 above Carhuaz, but the chances of an avalanche landing in an alpine lake might be increasing. Laguna 513 started to form in only the 1980s, according to Haeberli. Overdeepenings in current glacial beds are thought to be leading to the formation of similarly new lakes as the glaciers retreat and newly exposed carved bedrock fills with water.

Modeling glacier evolution

Haeberli’s Zürich colleague Andreas Linsbauer subtracts modeled ice thickness distributions from a surface digital elevation model (DEM) to derive glacier bed topography. He uses this information to model future glacier evolution and areas of overdeepening. ‘A large glacier with a big tongue has potential for more overdeepening,’ Linsbauer said.

Geomorphological characteristics of glacier beds of all Swiss glaciers detected 600 overdeepenings, 3% of which are larger than 0.5 km2 and coveri a total area of 50 to 60 km2. Assuming that current trends of glacier decline continue, 60% of the potential lakes would appear within the first half of this century. But how many would actually fill with water is a different question.

The glacial lakes described by Linsbauer’s model ‘can form anywhere,’ said Clague, and potentially ‘far from existing lakes.’ Ice has already carved the basins, and ‘eventually the glacier will retreat out of the basin and leave the lake behind.’ Linsbauer pointed out that new lakes could even be used for hydropower production, but they pose a serious hazard potential as they emerge in an increasingly destabilised environment—which Nevado Hualcan and Laguna 513 certainly illustrate.

Clague sees studies of glacier retreat, permafrost, avalanches, and glacial lakes not only as scientifically interesting studies of the processes that shape our planet, but also as contributing to more comprehensive models and a forecasting system for changing climate. But the people of Carhuaz would probably agree with Haeberli’s assessment that new hazard prevention methods are needed soon. And they wouldn’t be referring to ‘soon’ on a geological timescale.

Rachel Berkowitz