Early JWST targets set the stage for the next decade of observations

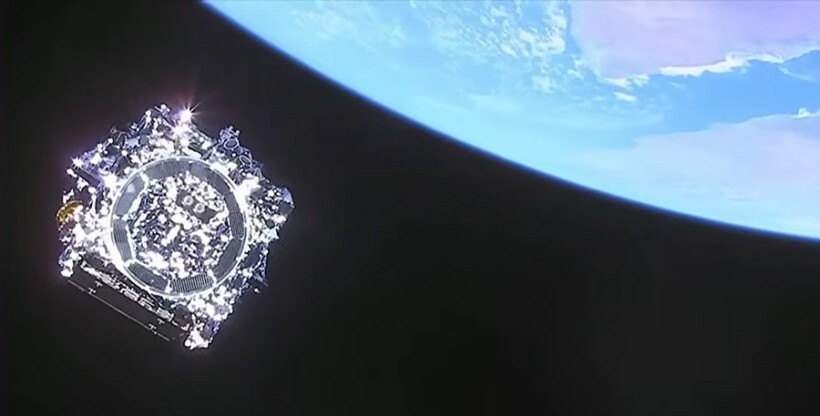

The JWST, which launched on 25 December 2021, drifts away from Earth.

NASA, ESA

In September 1989, as astronomers awaited the impending launch of the Hubble Space Telescope, Riccardo Giacconi, then director of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), challenged his colleagues to dream up a bigger and better successor. Those dreams are on their way to realization with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Launched in December and currently undergoing final calibration before science operations begin around 1 July, the JWST will look farther back in space and time than any of its predecessors, catching light from matter that illuminated the universe 13.6 billion years ago.

To explore how best to capitalize on the JWST’s capabilities, the STScI in 2017 devised the Early Release Science (ERS) program. On the basis of recommendations from the JWST Telescope Allocation Committee and detailed technical reviews, current STScI director Ken Sembach selected 13 projects

An unmatched IR observatory

When light from a distant or ancient object reaches us, its wavelength appears to be stretched, or redshifted, from the UV and optical into the IR. By observing at near- and mid-IR wavelengths (0.6–28 μm), the JWST’s instruments will see details in objects too old and distant for previous telescopes to examine. The near-IR also opens a window through dusty, visible-light-blocking outer layers of nebulae into their mysterious star-forming regions. Spectroscopy at those wavelengths will provide details of distant chemical compounds with a resolution high enough to separate tightly spaced spectral lines.

The JWST, with its 6.5 m primary mirror, isn’t astronomers’ first space-based IR foray. The Infrared Astronomical Satellite, run jointly by the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA, performed the first far-IR all-sky survey at 12, 25, 60, and 100 μm and catalogued 350 000 IR sources in 1983. Its successor, ESA’s Infrared Space Observatory, operated from 1995 to 1998. The two paved the way for NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. Launched in 2003, Spitzer was a foundational observatory that peered at the universe at the same set of wavelengths as the JWST but through an 85 cm primary mirror. In 2009 the Herschel Space Observatory brought a 3.5 m mirror to the game. It was designed to observe galaxies and dust-enshrouded regions inside the Milky Way, which emit most of their energy in the far-IR (60–500 μm). Also in 2009, astronauts added an exploratory near-IR channel to Hubble, but the heat generated by the telescope’s other instruments interfered with measurements beyond 2 μm.

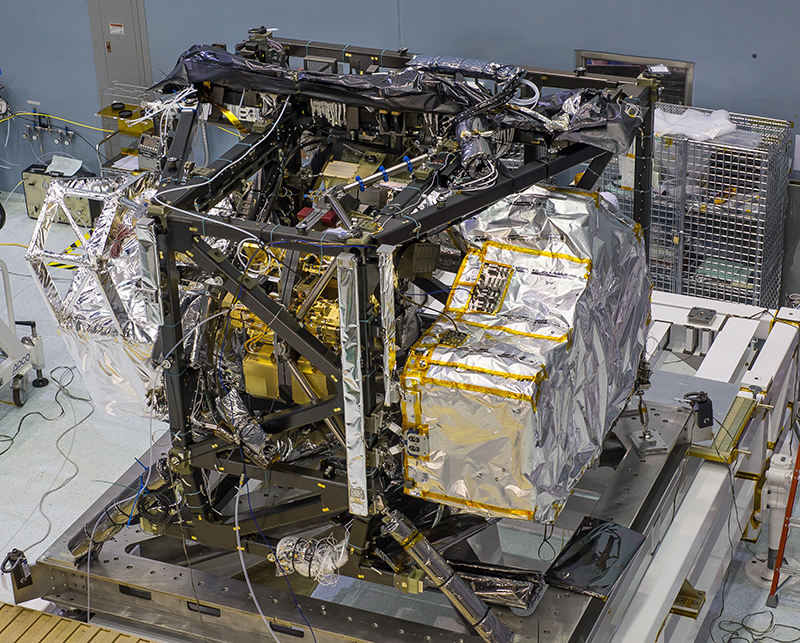

JWST instruments

The Integrated Science Instrument Module contains all four of the telescope’s imaging and spectrographic instruments. Click on each instrument to learn more about it. Credit: NASA/Chris Gunn

The Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) performs wide-field, broadband imaging and medium-resolution spectroscopy at 5–28 μm. By capturing light at these longer wavelengths, MIRI will allow astronomers to study objects such as stellar debris disks and extremely distant galaxies whose light has stretched into the mid-IR range. It has four coronagraphic masks that are designed for exoplanet studies.

The Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) is the telescope’s primary imager and the most sensitive camera on board, specializing in 0.6–5 μm light. Coronagraphic masks can be used to block out the bright light of a star from its nearby companions, including exoplanets.

The Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) addresses three wavelength bands within 0.8–5 μm. The accompanying Fine Guidance Sensor helps to point the telescope with extreme precision. NIRISS can achieve higher resolution than the other instruments through aperture masking interferometry (right), which involves taking in light from disparate apertures and combining the signals as if they had come from multiple telescopes.

The Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) is designed to observe dozens of objects simultaneously at high spectral resolution in the 0.6–5.3 μm wavelength range. Hair-width microshutters (right; scale bar 100 μm) open and close in response to an applied magnetic field.

Galactic archaeology

Cosmologists refer to some of the earliest days of our universe as the Dark Ages. Several hundred thousand years after the Big Bang, the cosmic soup of radiation and matter had recombined into neutral atoms, which are opaque to UV radiation. After several hundred million years of darkness, the neutral hydrogen that permeated the universe began to clump together under gravity and collapse, igniting nuclear fusion and leading to the first stars and then galaxies. Energy from those early stars heated and ionized the surrounding hydrogen, which in turn led to small local bubbles of ionized plasma that eventually overlapped and re-ionized the entire universe.

We have very few details about the re-ionization process, which represents a major transition in the evolution of universe structure, says UCLA astrophysicist Tommaso Treu. “We don’t even know where the re-ionizing photons came from.” His ERS program aims to find out. To determine which photon sources re-ionized the universe and precisely when they did so, Treu will use the JWST to take spectral images of early galaxies. Clues about re-ionization come from observations of highly redshifted emission lines associated with neutral hydrogen. Using several JWST spectrographs, his team will gather information about how gases in distant galaxies move and how they are distributed in space. “We’ll have the first maps of the earliest galaxies, both spatially and spectrally,” Treu says.

This Hubble view of galaxy cluster Abell 2744 shows intrinsically magnified light from faint, distant galaxies. By taking advantage of this lensing effect for redshifted light, the JWST will be able to create spatial and spectral maps of some of the first galaxies in the universe.

NASA, ESA

By providing the first-ever spectra of those targets, Treu’s project will also furnish future observers with information about how best to use each spectrograph on the JWST. The Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) is designed to observe 100 objects simultaneously at high spectral resolution in the 0.6–5.3 μm wavelength range. It is the first spectrograph in space to have that multi-object capacity, which is made possible by an array of hair-width microshutters that open and close in response to an applied magnetic field to control how light enters the instrument from different parts of the sky. The Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) addresses three wavelength bands within 0.8–5 μm. Depending on the cosmic targets, it can make a two-dimensional spectral map of all the galaxies in the field of view, disentangle blended objects within the same scene, and generate time-series spectra of transiting exoplanets. “There are different cases where you need different spectrographs, and we want to enable future users to make the optimal choice for their science,” says Treu.

Weisz will use the JWST to study the universe’s oldest galaxies in a different way: by studying the ages of stars in galaxies closer to home. In the very early universe, the first galaxies were small compared with what’s seen now. Most of those smaller galaxies eventually merged to form bigger ones, but some didn’t. “We’re left with some tiny, primitive galaxies in the early universe that we can’t see directly,” says Weisz. To piece together their histories, he looks to local galaxies that are deficient in heavy elements, or metals. He and his colleagues consider those galaxies to be surrogates for ones that existed in the early days of our universe, 12–13.5 billion years ago, before heavy elements had time to form.

Cosmic noon

The rate of star formation within young galaxies reached its peak 2 billion years after the first galaxies started to form, or about 10 billion years ago. Known as “cosmic high noon,” that epoch was marked by emerging stars converting lighter elements into heavier ones and pushing them out into the intergalactic medium. To understand the conditions that led to the stellar boom period, astronomers will use the JWST to examine the energetic processes that drive star formation and black-hole growth, an indicator of galaxy evolution.

To learn about galactic energetics, Lee Armus, a senior scientist at Caltech’s Infrared Processing and Analysis Center, and Aaron Evans, a professor at the University of Virginia, study local luminous infrared galaxies (LIRGs). They usually come in the form of merging spiral galaxies that produce stars at extremely high rates but are hidden by dust. “LIRGs are nearby laboratories of rapidly evolving galaxies we can study up close and learn about what distant galaxies were doing in their youth,” Armus says.

Luminous infrared galaxies such as NGC 3256, seen here in visible light by Hubble in 2018, provide a modern laboratory for examining star formation dynamics in the ancient universe.

ESA/Hubble, NASA

In the first cycle of JWST observations, Armus and Evans will observe four merging systems, each of which has at its center a region of higher-than-normal luminosity that results from either accretion of matter by a black hole or the production of huge numbers of hot stars. The JWST will target each galaxy nucleus with NIRSpec and with the Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam)—the most sensitive camera on board, specializing in 0.6–5 μm light—and the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), the workhorse camera–spectrograph combination that performs wide-field, broadband imaging and medium-resolution spectroscopy at 5–28 μm.

Those instruments will together capture the full IR range to see behind the dusty shrouds with nearly two orders of magnitude greater sensitivity than was previously available from the 85 cm primary mirror on Spitzer. The JWST should be able to resolve the speeds of gases swirling around black holes and the amounts of plasma flowing out. And it could provide direct evidence of hidden clusters of young stars, shock fronts from galactic winds, and the disruption of stellar nurseries by accreting black holes.

Baby worlds

Other early JWST users plan to look at objects closer to home. Astrophysicists Sasha Hinkley and Beth Biller, at the Universities of Exeter and Edinburgh, respectively, will use the telescope both to take images of young, nearby exoplanets at wavelengths that get obscured by Earth’s atmosphere and to search for new ones in the circumstellar debris disks where they’re likely to have formed. The challenge is resolving planets when their host stars are 10 000 to 1 million times as bright as they are. “We have to reduce the glare,” says Biller.

She and Hinkley plan to do that by utilizing the coronagraphs on NIRCam and MIRI, which can block out starlight at different wavelengths. In addition, the team will use the NIRISS instrument to combine light from individual segments of the telescope’s primary mirror to create an interferometer. Instead of allowing light to enter through one aperture, a mask allows light in through seven mini-apertures to create 21 unique pairs of baselines, much like a telescope array on Earth. The improved angular resolution will allow a search for additional planets that might otherwise be too close to the host star to detect directly. And high-resolution spectroscopy carried out on NIRSpec and MIRI will give the JWST access to much more precise chemical abundance data, resulting in unprecedented measurements of exoplanet composition. “That’s important for learning about how they formed, which is ultimately our goal,” says Hinkley.

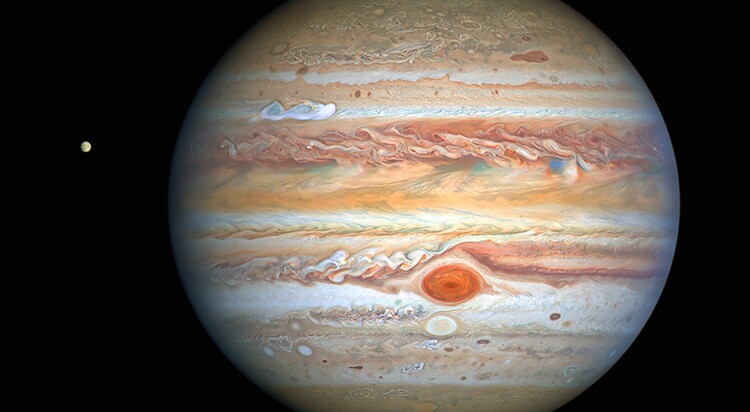

This view of Jupiter and its moon Europa (left) was captured by Hubble in 2020. Researchers plan to use the JWST to make detailed measurements of the Jovian moons, whose light is difficult to resolve from Jupiter’s.

NASA, ESA, A. Simon (Goddard Space Flight Center), and M. H. Wong (University of California, Berkeley) and the OPAL team

Another early trial of the telescope’s ability to resolve faint objects from nearby bright ones will focus on a target within the solar system. Imke de Pater, an astronomer emerita at UC Berkeley, intends to push the JWST to its limit by observing the relatively faint rings and moons next to big, bright Jupiter. Sensitive spectroscopic measurements of Ganymede and Io will discriminate among different gases, including water vapor and sulfur monoxide, to see how they are distributed in the moons’ atmospheres, potentially enabling the first-ever determination of the surface temperatures on those bodies. “This is something that’s totally unknown,” says De Pater. As part of their investigation, members of De Pater’s team will write software that subtracts unwanted background light to analyze faint features of interest. They intend to share the software with anyone planning to make bright-background observations with the telescope.

As De Pater’s project demonstrates, the ERS programs are designed to get the community up to speed on the JWST’s instruments and capabilities. “In some sense we’re the beta testers of the instruments,” says UCLA’s Treu. The next set of approved observing proposals, known as Cycle 1 General Observers, will begin alongside the ERS program around 1 July and continue for a year.