DOE Will Stop Funding Particle Physics at Brookhaven Accelerator

DOI: 10.1063/1.1480772

Faced with a very tight presidential budget, the US Department of Energy has announced that it will no longer fund the operation of high-energy physics experiments at Brookhaven National Laboratory’s Alternating Gradient Synchroton in fiscal year 2003. The AGS, a 30-GeV proton accelerator, began its illustrious career in 1961. Barring a congressional reprieve, DOE’s announcement means the abrupt end of the venerable accelerator’s two ongoing particle physics experiments.

In this era of TeV colliders, it sounds quaint to speak of high-energy physics experiments with 30-GeV protons. But the two highly visible AGS experiments—a search for an extremely rare K+ decay mode and a precision measurement of g µ−2, the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon—are oft-cited examples of the unique contributions that experiments at accelerators of modest energy but very high beam intensity can make to particle physics.

When it’s not accelerating protons, the AGS nowadays accelerates heavy ions for injection into Brookhaven’s two-year-old Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider. RHIC, which is now Brookhaven’s flagship program, accelerates ions as heavy as gold to 100 GeV per nucleon. It is funded by DOE’s nuclear physics program, which will continue to run the AGS as RHIC’s injector. But filling the big collider takes only a few hours a day. What will no longer be funded is the relatively small incremental cost ($7–8 million a year) of operating the AGS as a proton accelerator for particle physics experiments during the remaining 20 hours a day. The operating cost of RHIC, by comparison, is about $100 million a year.

Looking for one in ten billion

The rare K+ decay experiment, designated E949, is a particularly hard case, facing extinction just a few months into its run. In a decade of running, its predecessor experiment, E787, found only two

That’s not far from what the standard model of particle theory predicts for such a “flavor-changing neutral-current” process. But with its much upgraded sensitivity, E949 was expected to harvest 10 times as many of the rare decay events in the next three years, making it possible to confront crucial aspects of the standard model with extraordinary precision.

“On the strength of DOE’s assurance, admittedly with caveats about budget catastrophes, that we’d be able to finish the run, our foreign collaborators spent about $5 million, not to mention their time, on upgrades for E949,” says Brookhaven group leader Laurence Littenberg. “It’s a horrendous breach of faith. Two-thirds of the collaboration are from groups in Japan, Canada, and Russia. Good luck to us when we go looking for foreign contributions to the Next Linear Collider.” (See January 2002, page 23

“We take no pleasure in these cuts,” says Peter Rosen, director of nuclear and high-energy physics programs at DOE. “But we have to confront severe budget constraints. In making these painful decisions, we’re guided by the priorities set by HEPAP [the High Energy Physics Advisory Panel].”

In the president’s FY 2003 budget, the $725 million for DOE high-energy physics programs is an increase of only 1.7% over this year’s appropriation (see the story on page 30 of this issue). That’s less than inflation. Among existing particle physics experiments funded by DOE, HEPAP has assigned the highest priorities to the search for manifestations of the Higgs mechanism and supersymmetry at the Fermilab Tevatron, and the study of B-meson physics at the SLAC B factory. The tight FY 2003 budget certainly affects Fermilab and SLAC. But at those labs, the result is expected to be a general belt-tightening rather than the shutdown of ongoing experiments.

The rare K decay experiment was intended to measure the same CP-violating parameters one measures, at much higher cost, at the B factories (see Physics Today, May 2001, page 17). “Whether one gets the same result for K and B mesons is a major theoretical issue,” says Brookhaven associate director Tom Kirk.

Measuring the moment

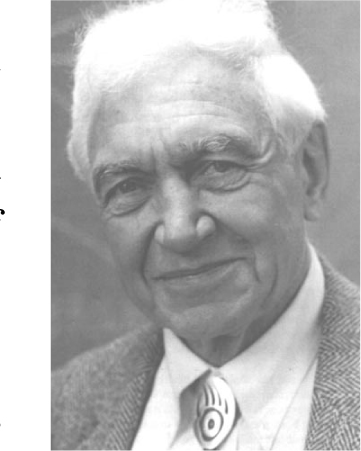

The prospective fate of the g µ−2 experiment is not as egregious as that of E949. Running since 1999, the g µ−2 collaboration was not explicitly promised any more AGS time beyond this year. “But one more year would bring the precision of our measurement to our goal of 0.4 parts per million,” says Vernon Hughes (Yale University), who began this undertaking 20 years ago. “That would give us a unique opportunity to test, with unusual sensitivity, for supersymmetric departures from the standard model.” (See April 2001, page 18

Unlike the precision measurement of g µ−2, the study of rare K decays has foreseeable prospects for life after the end of DOE funding for particle physics at the AGS. In FY 2004, NSF is expected to fund construction, at the AGS, of an ambitious experiment called KOPIO, which will search for

Vernon Hughes has been striving for 20 years to measure the muon’s anomalous magnetic moment to within a few parts in 10 million.