Dirty water

DOI: 10.1063/PT.4.2401

Down by the banks of the river Charles at the AAAS Annual Meeting last month, Edie Widder told a story about the recent loss of a rain forest’s worth of seagrass meadows at Florida’s Indian River Lagoon.

The lagoon’s rich biodiversity depends on five species of seagrass. Non-point pollution sources affect water clarity, which in turn determines the light that reaches the seagrass and thus the health of the plants. High pollution levels also impact estuary denizens: Photos of oysters tinged with copper and turtles crusted with tumours drew gasps from Widder’s audience.

But Widder and her team at the Ocean Research and Conservation Association (ORCA) don’t love that dirty water; they are committed to adapting scientific methods to analyze the ecosystem stressors and mobilize political support to deal with those pressures.

Pollutants collect in sediments on the lagoon floor, but pinpointing their location takes time and money. So ORCA developed the Fast Assessment of Sediment Toxicity (FAST

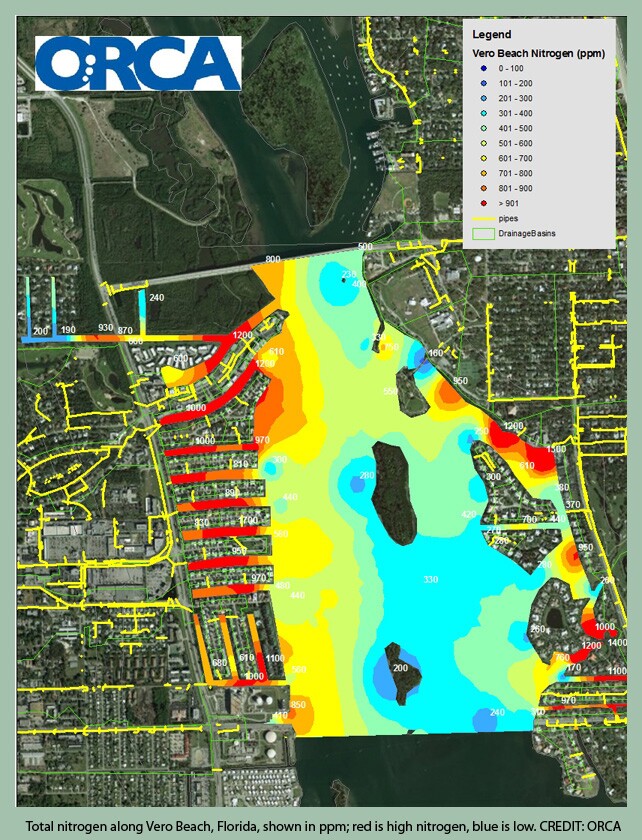

One study showed comparable results to a Smithsonian biodiversity study, in which low toxicity was correlated with high biodiversity. The resulting pollution maps, which provide an accessible visualization tool, influenced the city of Vero Beach to pass a fertilizer ordinance.

The maps show where the most polluted areas are, ‘but you cannot address where [the pollutants] come from unless you can monitor flow patterns over time,’ Widder says.

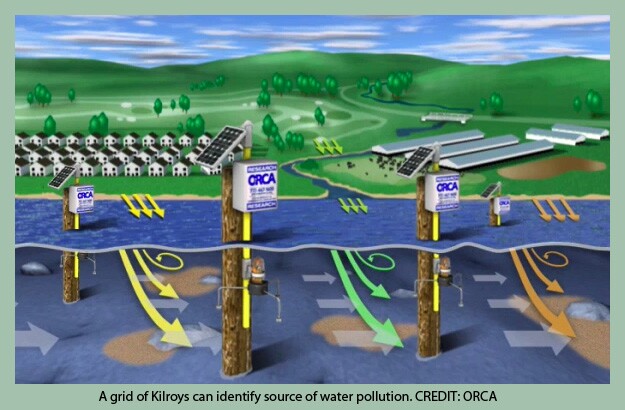

Enter Kilroy: ORCA’s own real-time wireless underwater sensor suite for ecosystem monitoring. This football-sized device measures water flow speed, direction, turbidity, and biological properties, and transmits data to shore via the internet. A grid of Kilroys stationed in the Lagoon will facilitate the creation of a pollution gradient map once all flow fields have been calculated. The Kilroys will also be coupled with a water sampler set, which will trigger when a turbidity current passes by, and determine whether the current carries stormwater sewage, diesel fuel, or other particulate.

Data from Kilroy will allow ORCA to identify pollution sinks, map their dispersion, create an overall picture of where stressors come from, and provide the necessary information to stop them at the source.

However, enforcing the Clean Water Act, which establishes the basic structure regulating discharge of pollutants into US waters, requires an Environmental Protection Agency technician to handle any water sample used to inform regulation. Thus, Kilroys are designed to call a cell phone each time a sample is taken, so an EPA-certified lab can be notified and the sample processed immediately.

Widder ultimately hopes to install Kilroy monitoring systems in other parts of the world and provide a global picture of pollution sources and sinks (think Google Earth). As ever, funding is problematic, but may come from insurance companies, or real estate investors.

As for outreach, ORCA promotes awareness by taking school children out to collect sediment samples, process data, and communicate findings. ‘Kids are learning that there is no answer in the back of the book,’ Widder adds.