Diamond nanoneedles turn metallic

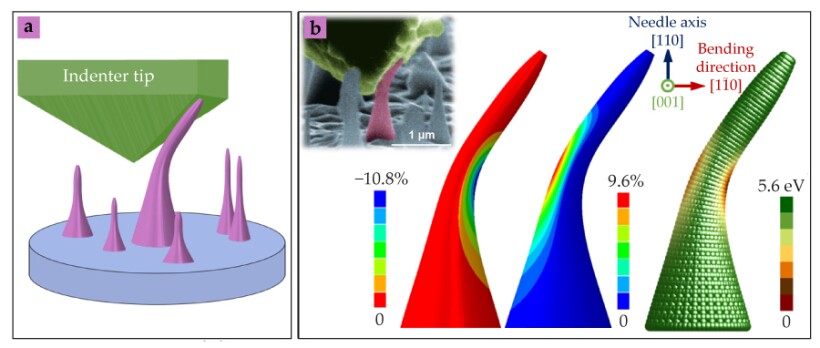

If you ever manage to deform a diamond, you’re likely to break it. That’s because the hardest natural material on Earth is also inelastic and brittle. Two years ago, Ming Dao

Z. Shi et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 24634 (2020)

The achievement prompted the researchers to investigate whether the simple process of bending could controllably and reversibly alter the electronic structure of nanocrystal diamond. Teaming up with Ju Li

Band engineering using elastic strain is not new. More than two decades ago researchers found applications in microelectronics using engineered strain in silicon. But the strains applied to Si were on the order of 1% or so. According to the new calculations, diamond nanoneedles can be repeatedly exposed to local compressive strains up to −10% on one side and tensile strains above 9% on the other, as shown in the figure—without fracturing or transforming into graphite. The ability to engineer electrical conductivity in diamond without changing its chemical composition or stability opens several specific applications. For example, a tiny piece of bent diamond, with a strain gradient due to bending, could be fashioned into a solar cell or photodetector that captures a range of light frequencies on a single device. Today, that broad-spectrum approach requires layering different materials to take advantage of their different absorption bands. (Z. Shi et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 24634, 2020