Cracking the code of scientific Russian

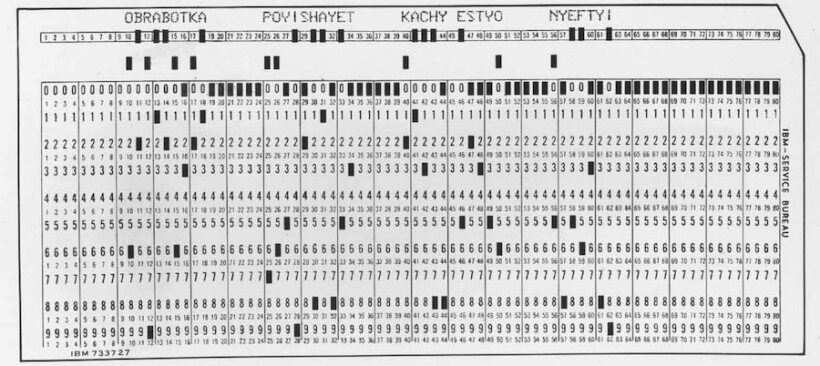

This punch card for the IBM 701 computer contains a Russian sentence to be translated. The computer correctly translated the phrase as, “Processing improves the quality of crude oil.”

Georgetown University Archives

It was the early days of the Cold War, and American scientific leaders were worried. The Soviets were writing scientific papers. In fact, they were writing quite a lot of them, and they were writing them in Russian. A 1948 study showed that of all the scientific papers published in a language other than English, one-third were in Russian, a proportion that would surely climb after a Communist Party declaration requiring Soviet scientists to publish their work in the country’s most used language.

English-speaking scientists were thus faced with an ever-expanding mountain of scientific publications in a language very few of them spoke. Keeping up with it seemed like a daunting task. In response, US scientists turned to language courses and human translators and even produced some of the first computer translation programs. Princeton historian Michael Gordin chronicles those efforts in his recent book, Scientific Babel: How Science Was Done Before and After Global English. He finds that ultimately, US efforts to tame the Russian scientific literature may have helped cement English as the new dominant language of science.

Technical Russian for busy scientists

The existence of a large body of scientific literature in a language other than English was hardly a new problem. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, German was the prevailing language of science. Many serious researchers adapted by learning German or studying at a German university

But few thought the situation was hopeless. By the 1940s, Gordin writes, there was a growing belief among US scientists that translating “scientific Russian” or “technical Russian” was a task fundamentally different from translating The Brothers Karamazov. Scientific writing used primarily the passive voice, had fewer verb tenses, and employed a limited, specialized vocabulary. Though it might be difficult for an adult to master Russian, many scientists believed that learning to read a Soviet researcher’s organic chemistry paper would be a comparatively simple task.

In 1942 George Znamensky, a professor at MIT, began teaching a weekly seminar aimed at enabling students to read scientific articles in Russian. Sixteen years later, chemist Irving S. Bengelsdorf had a surprise hit on his hands with his television series Basic Russian for Technical Reading. The 12-week course was originally expected to draw an audience of roughly 250 upstate New York scientists but ended up with more than 10 000 regular viewers.

The machine translation movement

Not everyone considered teaching scientists to read Russian the best solution to the Russian literature problem. Warren Weaver, the longtime natural sciences director of the Rockefeller Foundation, had another idea: Program a computer to translate.

Despite an effort to use the IBM 701 computer to translate Russian science papers, the machine translation movement never got far.

Georgetown University Archives

In a widely circulated 1949 memorandum, Weaver suggested that translating Russian was really a problem of code breaking, a task that early computers had tackled to celebrated effect during World War II. “When I look at an article in Russian, I say: ‘This is really written in English, but it has been coded in some strange symbols. I will now proceed to decode,’” he wrote. Even if the translating computer “would translate only scientific material (where the semantic difficulties are very notably less), it would seem to me worth while.” Here again, we see the belief that scientific material was fundamentally easier to work with than everyday Russian.

In 1952 Weaver sponsored the first Conference on Machine Translation at MIT, bringing together a small community of scholars interested in MT, as the field came to be called. One of the attendees was Léon Dostert, head of the Institute of Languages and Linguistics at Georgetown University. Dostert arrived in Cambridge as a skeptic of MT but left a convert.

Dostert quickly became MT’s most recognizable public face. He partnered with IBM on an effort to program the company’s 701 computer to translate Russian scientific papers into English. By 1954 Dostert was headlining dramatic public displays in which the 701 was fed punch cards with Russian phrases and printed out English sentences “at the breakneck speed of two and a half lines per second,” according to an IBM press release. Others in the MT community resented Dostert’s high profile—his own scholarly contributions to the field were relatively limited—but the controversial administrator was gifted at securing federal grant money, not just for himself but for MT research in general.

The MT boom was not to last. Dostert’s program knew only 250 words of Russian and six basic syntax rules—not enough to translate even scientific Russian with any kind of speed or volume. Dostert forged ahead, optimistic that just a few years of concentrated effort would result in a computer that could mass-translate scientific Russian, but by the mid 1960s his patrons in the US government were tired of waiting. A 1966 National Academy of Sciences report

A market for translations

Long before the National Academy published its report favoring human translators, an enterprising publisher had arrived at the same conclusion. Earl Maxwell Coleman was the founder of a company called Consultants Bureau, which got its start by translating German technical documents captured by the Allies after Germany’s surrender. The market for that kind of translation was limited, so Coleman quickly turned his attention to translating Russian scientific journals. The Consultants Bureau journals achieved profitability, in part, by paying translators the incredibly low sum of $4 per thousand words instead of the industry standard of $12. To Coleman’s advantage, the low rate appealed only to translators who were fast enough to make a living wage off the sheer volume of steady work he offered.

The American Institute of Physics (AIP, which publishes Physics Today) also entered the translation market. In 1955, backed by a generous NSF grant, AIP began publishing Soviet Physics—JETP, a journal that contained translations of the papers in the Soviet Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics. The publication was an immediate hit with subscribers, and AIP quickly expanded its translation project to include smaller periodicals like Soviet Aeronautics.

The American Institute of Physics relied on a hefty NSF grant to publish Soviet Physics—JETP.

AIP Niels Bohr Library & Archives

However, AIP soon found that it could not keep up with the growing size of Soviet scientific journals. Soviet Physics—JETP was cost-effective to produce when JETP published 1500 pages per year, but by 1965, it had ballooned to 4500 pages annually. In the late 1950s, an overwhelmed AIP began farming its translations out to Coleman’s stable of translators, and by 1968 Coleman was producing all of AIP’s translation journals. Coleman’s Consultants Bureau (later renamed the Plenum Publishing Company) became the undisputed Cold War king of translated scientific publications, bringing the work of heavyweight physicists such as superconductivity pioneers Alexei Abrikosov and Lev Gor’kov to the attention of English-speaking researchers.

English as a scientific language

The success of the Consultants Bureau journals did not merely enhance the company’s bottom line. Gordin suggests that the availability of English translations of Soviet journals played an important role in making English the most common scientific language in the world.

Scientists from smaller language groups wanted to follow developments in both American and Soviet science. Few American papers were translated into Russian, for the simple reason that many Soviet scientists already spoke excellent English. But if Russian-language journals were systematically translated into English, scientists in rising scientific powers like India and China could keep track of both literatures by learning only one of the languages: English.

This, writes Gordin, combined with an international backlash against the German language in the wake of World War II, set the stage for English to take German’s place as the most frequently used language of scientific conferences, collaborations, and publications. In 1960, English-language papers accounted for around 50% of the scientific literature; by 2005 that figure had reached 90%. It is a dominance that seems unlikely to shift anytime soon—but that does not mean it is written in stone. “The history of scientific languages ends here,” Gordin writes, “until it no longer does.”

Michael Gordin will deliver the next Trimble Science Heritage Public Lecture in College Park, Maryland, on 18 October. To RSVP for his talk, “Scientific Babel: English, German, and the Fall of Polyglot Natural Science,” please visit this website