Conference organizers, potential participants fault US policies for falling attendance

DOI: 10.1063/pt.iukf.ljdu

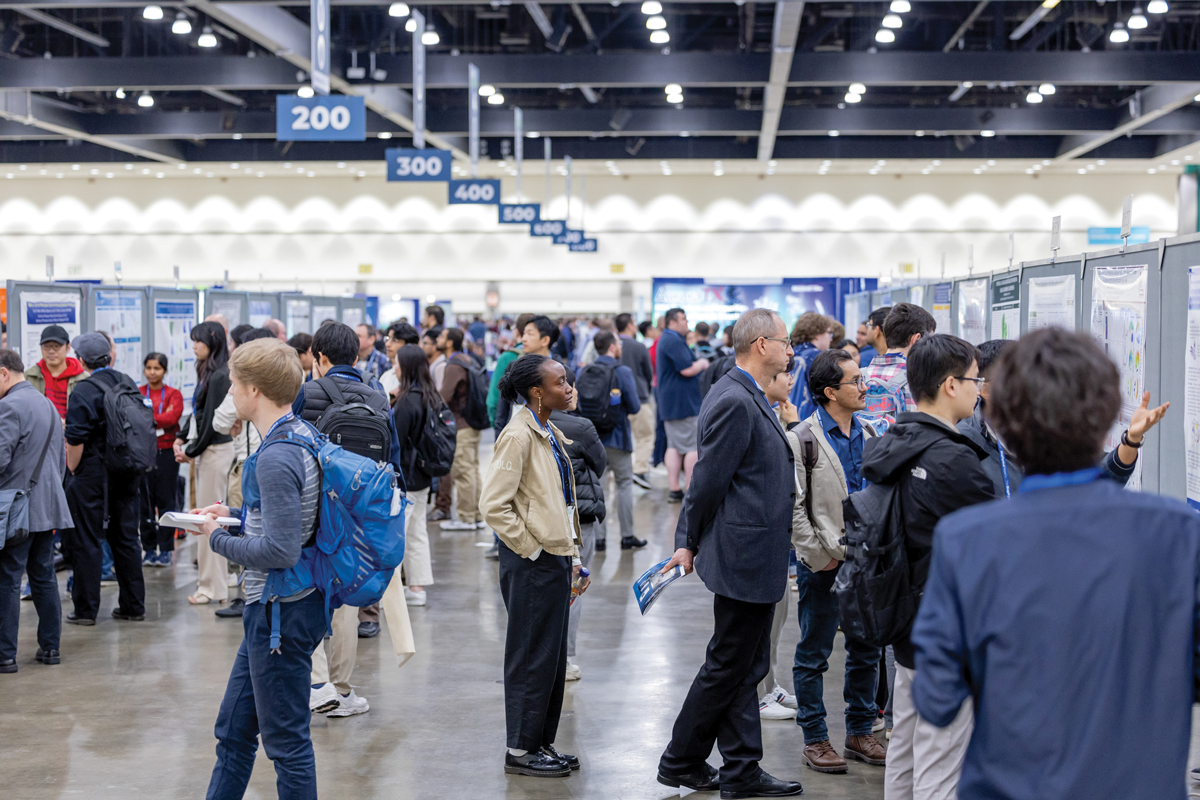

The Global Physics Summit, the American Physical Society’s meeting in March, drew more than 15 000 attendees. But many conferences are seeing drops in participation and cancellations among speakers. (Photo courtesy of APS.)

An early-career researcher at a major US university was thrilled to be invited to speak at the International Liquid Crystal Elastomer Conference this August. Presenting would be a feather in their cap and an opportunity to network and learn about state-of-the-art developments in their field.

But in May, the researcher contacted the conference organizers to cancel: The event takes place in Finland, and with heightened scrutiny of travelers under the Trump administration, the researcher, an assistant professor who is from China, decided not to risk being denied reentry into the US. (This researcher and a handful of others, including US citizens, who spoke with Physics Today requested anonymity so as not to draw attention to themselves or their institutions.)

Visa woes and worries about being hassled, detained, or denied entry at the US border are contributing to falling attendance at many scientific conferences. So are cuts and threats to funding, rules that hamper travel for scientists employed by the US government, and protests against new US policies by potential participants. Statistics are not yet available—and many professional societies keep details close to the vest. Even before this year, conference attendance had taken hits from COVID-19 and concerns about the impact of travel on climate change (see Physics Today, May 2023, page 23

Some organizers are canceling conferences or moving them online or out of the US. And many scientists are adjusting their conference-attending strategies, with US-based researchers looking more locally and non-US based ones focusing outside the US.

Reconsidering conference travel

This year’s International Conference on Supersymmetry and Unification of Fundamental Interactions is planned for mid-August at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Conference co-chair Howard Haber expects about 150 participants, down from around 200 in recent years. He says that some international scientists have canceled their participation because they are “spooked by stories in the news of scientists and tourists who have been detained” by US border security.

Warwick Bowen, a quantum physicist at the University of Queensland in Australia, organized Gordon Research Conferences in the US and in Switzerland this summer. Through the US National Institutes of Health, the conferences provided travel money to participants, but the money was delayed, says Bowen, which meant that “we were unable to support people who depended on the assistance.” And, he adds, the showing of US-based scientists at the July meeting in Switzerland would likely have been larger “if not for the visa issues.”

The Canadian Association of University Teachers has advised academic staff that they should travel to the US only if essential, “given the rapidly evolving political landscape in the United States and reports of individuals encountering difficulties crossing the border.” The advisory recommends that academics exercise particular caution if, for example, they “have expressed negative opinions about the current U.S. administration or its policies,” their passports bear stamps showing recent travel to countries that have diplomatic tensions with the US, or they are transgender. Some countries have issued similar advisories.

With colleagues who are members of groups that are “being overly scrutinized and challenged at the border, I feel like, in solidarity, I should not enter the US right now,” says Nancy Forde, a physicist at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia. Moreover, she says, she doesn’t want to support the US economy when President Trump is threatening her country’s sovereignty. But she does want to “engage in great scientific discussions with colleagues in the US and from around the world. It’s tricky.”

Forde attended the APS Global Physics Summit. It was the first time she found it stressful being in the US: “I wondered, if I jaywalked, could I be deported?” She is weighing whether to honor her commitments to present at other upcoming conferences in the US. “I now make sure my flights are fully refundable,” she says.

The Biophysical Society Meeting in Los Angeles last February saw attendance within its usual range of 4000–5000. But the society refunded about $20 000 total to scientists, including more than two dozen speakers, who canceled because of travel restrictions for US government employees. (Photo by Brandon Ogden, courtesy of the Biophysical Society.)

Barry Sanders of the University of Calgary in Alberta says that a small conference on quantum information that he had planned to attend in early May at the University of California, Berkeley, was canceled. Between objections from Canadian participants about going to the US and worries by some US-based researchers about reentering the US if a meeting is moved outside the country, he says, “we are still discussing how we will handle our next meeting.” He adds that his students are increasingly choosing to attend conferences in Europe.

A researcher at a top US institution who requested anonymity says that they pulled a student from participating in a meeting in Europe because of funding concerns. That student will instead attend a local conference. “We have a lot of free or low-cost, one-day conferences close by,” says the researcher. “I think we will go to more of those and fewer of the big national and international meetings.”

Hoops and symptoms

Scientists who work for the US government are having to forgo conferences or jump through more hoops to attend them. Last February, when the Biophysical Society held its annual meeting, NIH scientists’ travel was restricted. Some 29 speakers canceled, says Lynmarie Thompson, the society’s president and a professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Sessions to help researchers navigate applying for grants from NSF and NIH had to be canceled.

Peter Littlewood, a physicist at the University of Chicago, is running a conference on AI and energy in London this September. It is jointly sponsored by NSF and the Royal Society, but, he notes, US participation is limited by US government employees’ “current inability to use federal funds for travel.”

Many conference goers and organizers mentioned similar scenarios: A NIST scientist withdrew from a conference because it wasn’t “mission critical”; an NIH physicist was unsure they could attend a conference until they received approval at the last minute; government scientists seek nongovernment money—or pay out of pocket—to attend conferences. Some government employees have second affiliations that they can travel under. Several government scientists and agency spokespeople declined requests to speak with Physics Today or did not respond.

Visa hurdles are not limited to the US. Chinese visitors face problems entering India, too, and for people of some nationalities, getting a timely visa to enter Europe can be a challenge. Some conferences alternate their locations to distribute the burdens of travel, cost, and visas.

Conference venues are often booked years in advance. Beth Cunningham, the CEO of the American Association of Physics Teachers, says that the association faces a penalty if fewer than 80% of rooms are booked at a conference center. “We have hotel contracts through 2027,” she says, “but we are holding off on future contracts until we have a better understanding of what we need.” She attributes the drop in attendance to the rising costs of registration and hotels, restricted budgets because of threatened and cut grants, and increasing consciousness about carbon footprints.

An officer from another professional society who requested anonymity notes that sinking conference attendance has broad implications for all professional societies: “reduced revenue, increased instability, declining participation and engagement, and heightened uncertainty regarding the future of conferences, all society products, and the future of scientific associations overall.”

Conferences are critical for training new generations of scientists, says the Biophysical Society’s Thompson. “They get exposure to other fields and approaches, receive feedback on their work, and form collaborations.”

Thompson and others stress that falling conference attendance is symptomatic of larger issues. The threatened funding cuts will significantly reduce the number of research projects and the number of students and early-career researchers who can enter STEM fields, notes Santa Cruz’s Haber. If they materialize, he says, “it will decimate science research and innovation in the US. It will take a generation to repair.”

This article was originally published online on 9 July 2025.

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org