Biological tissue that behaves like liquid crystals

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.7371

Consisting of a small number of cell layers, an epithelium is the protective membrane that lines embryos and organs. The cells themselves form a dense colony whose local tension fluctuates as some cells are born and others die during morphogenesis, growth, and tissue repair. Despite the ubiquity of those processes, however, scientists have never completely understood the mechanical and biochemical mechanisms that determine which cells are targeted for removal from the tissue. Researchers from the Mechanobiology Institute

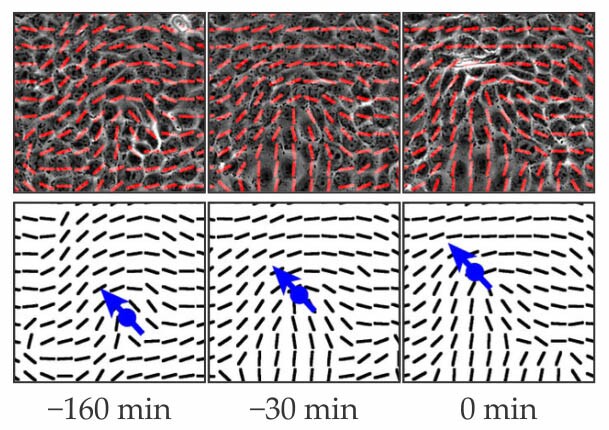

Like collagen-producing fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and lipids, some types of epithelial cells are rod shaped. The anisotropic shape prompts them to spontaneously align, much like liquid crystals, into ordered domains that lower their collective free energy. And like liquid crystals, the cellular packing contains topological defects—misalignments in the long-range order that punctuate the separate domains. The MBI team and their colleagues cultured canine kidney epithelial cells into monolayer sheets, a geometry that produces well-defined defect configurations. In their analyses of microscope images, the researchers found that cells were extruded from the tissue predominately at defect sites that resemble comets, with cells in the head perpendicular to those of the tail. By measuring and simulating the compressive stress at such defects, they ascribed a causal role to the correlation: The stress from the distortion caused by the misalignment builds up for hours prior to an extrusion event as cells in the tail overcrowd those in the head. The phase-contrast images shown here (top) and their black and white projections (bottom) of local cell orientations and defect-core (blue) position and direction of motion illustrate the time evolution, with an extruded cell visible in bright white at time zero.

The researchers also deliberately induced defects in their samples. The trick was to culture the cells in a star-shaped geometric configuration, which promotes defect formations along the highly curved edges. The demonstrated control over defect density may chart a path for scientists trying to cure cancerous tumors and other pathological tissue in which the process of cell death has gone awry. (T. B. Saw et al., Nature 544, 212, 2017