Big data goes high-speed across the Atlantic

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.2617

A new transatlantic network opening in January is the first of numerous high-speed intercontinental connections that will be needed in the years ahead as scientific facilities under construction around the world begin generating enormous amounts of information for analysis.

The transatlantic extension of ESnet, the US Department of Energy’s Energy Sciences Network, is designed to benefit data-intensive scientific collaborations at US national laboratories and universities. Its initial application will be moving data from experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which is set to resume operations in April 2015. Brookhaven National Laboratory and Fermilab will continue as the primary computing centers for US collaborators in the LHC’s ATLAS and CMS experiments.

The intercontinental network will provide an aggregate capacity of 340 gigabits per second by making more efficient use of existing undersea cables. That compares with the approximately 60-Gbps link that had been available up to now. Apart from the LHC, the network will later provide a two-way highway for the transoceanic flow of data generated by scientific computing centers, synchrotrons, neutron sources, and other science facilities.

Based at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, ESnet connects the DOE national laboratory system, providing data transfer and access to remote scientific facilities for tens of thousands of collaborating scientists. Founded in 1986, soon after the advent of the internet, ESnet completed an upgrade in 2012 and became the world’s first continental-scale 100-Gbps network.

Greg Bell, ESnet director, says that the additional network capacity has been leased for one- to three-year terms on four existing undersea cables. A fifth, backup cable will minimize the chances of a complete network outage in the event of a hurricane or other disaster. It’s not unusual for several undersea cables to be cut or damaged at a given time, usually by ship anchors. Repairs at sea can take four weeks or longer.

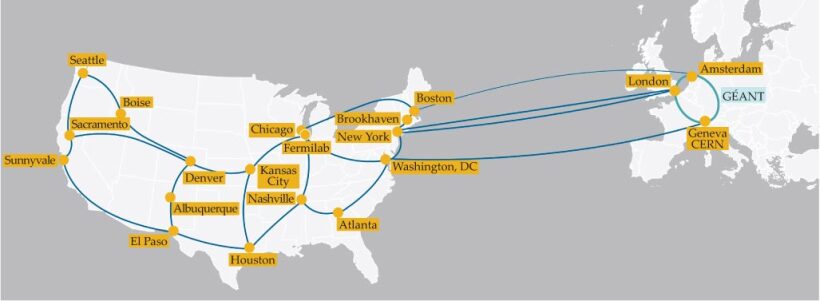

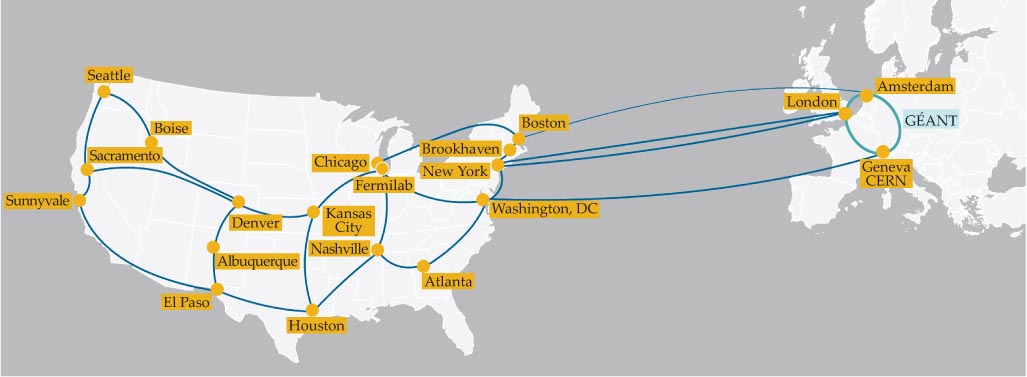

Just last year six organizations (ESnet, Internet2, and Canada’s CANARIE networks in North America and the SURFnet, NORDUnet, and GÉANT networks in Europe) deployed the world’s first 100-Gbps transatlantic research link. ESnet installed its first European network node at CERN in mid-September. The plan is for all four ESnet links (see figure below) to Europe to be operating by next month.

The transatlantic extension of ESnet, the Department of Energy’s scientific network, involves four cables originating at different locations in Europe and the US. The internal ESnet backbone connects to the DOE national lab network. GÉANT, the European research and education network that features internal data transmission speeds of up to 500 gigabits per second, connects the European nodes.

LAWRENCE BERKELEY NATIONAL LABORATORY

Bell says the new transatlantic network capacity will be sufficient for the next three years or so. “I feel confident this capacity will need to grow in the future, though, because scientific data carried by ESnet has been growing on a steady exponential rate since the early 1990s. In fact, many research networks are growing at about twice the rate of the commercial internet” he says.

Until now, transatlantic connections haven’t kept pace with the 10-fold increases in data transmission rates that have been achieved through new optical and digital signal processing technologies. The higher performance is achieved by upgrading the capacity of data streams that travel separately and simultaneously via 80 slightly different frequencies of laser light along a single optical fiber, a technology known as dense wavelength division multiplexing.

An avalanche of data

Brookhaven physicist Michael Ernst, who directs the central computer hub for US collaborators on the ATLAS experiment, says the data from the LHC are time sensitive in part due to the competition among researchers to be first with discoveries. At 13 TeV, the upgraded LHC will produce proton collisions with nearly twice the energy of those seen in the 2010–12 run. About 40 petabytes of raw data per year are expected, compared with the 20 petabytes that were produced during the entire three years of the previous run.

An added feature of the higher-speed intercontinental connection will be more agile access to LHC data by US researchers. Instead of the current system’s hierarchical flow through the national labs to university researchers, data can now be fetched more flexibly and dynamically and at higher speeds by all users, says Ernst.

Elephants and mice

Elsewhere, national networks have been collaborating for the past 18 months to test high-speed undersea connections. In September, Research and Education Advanced Network New Zealand announced the prototype deployment of what it claimed to be the longest undersea 100-Gbps link, spanning 20 500 km from New Zealand to California. The group’s chief executive, Steve Cotter, is a former director of ESnet.

Particle physics has been “at the absolute forefront of pushing networking technology and demonstrating to the rest of the world what can be done if we build fast networks between major facilities,” says Bell. Physics facilities in Asia and telescopes in South America will be major drivers of improved transoceanic links, he says.

Every three days the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope will cover the entire sky visible from Chile and produce data that cosmologists will need access to in a timely fashion, says Ernst (see Physics Today, September 2012, page 22

Similar network requirements will come from the Daya Bay Reactor Neutrino Experiment in China and from the upgraded Belle detector at Japan’s KEK, beginning around 2016–17, Bell says. “We think the Japanese research networks have the primary responsibility for the data transfer across the Pacific,” he says. ESnet will transfer that data to Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and then to research centers in the US and Europe.

“I’m exposed to a lot of international collaborations, and one thing they have in common is a need for high-speed, really reliable, nearly flawless data transport,” says Bell. Very large point sources of data—what he calls elephants—are very sensitive to flaws in the network, whereas the “mice”—everyday video flows, email, and Web browsing—can tolerate networks that occasionally drop packets.

More about the authors

David Kramer, dkramer@aip.org