Author Q&A: Science photographer Felice Frankel

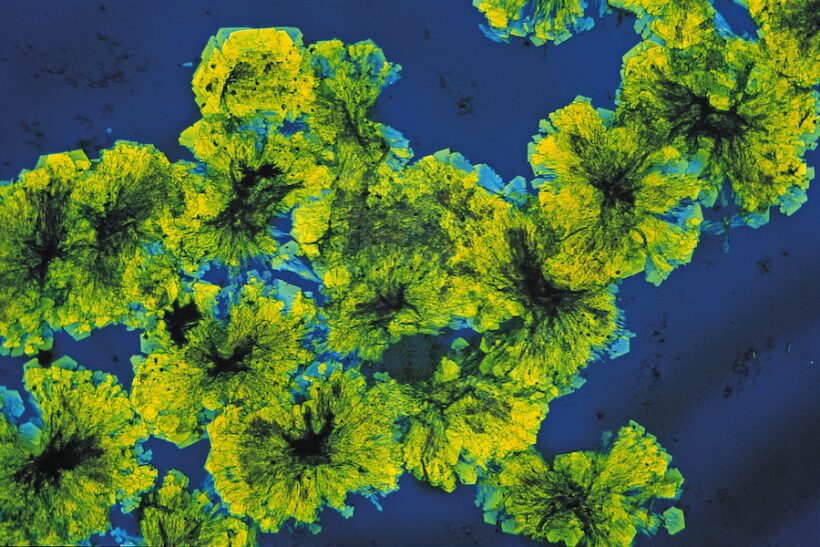

Quantum dots. © Felice Frankel

Photographer Felice Frankel

Frankel’s knowledge is on full and stunning display in her new book, Picturing Science and Engineering. The book advises researchers on how to produce beautiful images with cell phone cameras, flatbed scanners, and microscopes and explains how to use those photographs to present science to the world. In the May issue of Physics Today, Mark Ratner calls the book

PT: How did you become interested in scientific images?

FRANKEL: I’ve always been enormously curious about nature, and I have an undergraduate degree in biology. Photography came later. I ultimately became an architectural photographer for various magazines and companies, taking photographs of buildings and designed landscapes. After publishing my 1991 book, Modern Landscape Architecture [with coauthor Jory Johnson], I received a Loeb Fellowship at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. It was a really extraordinary experience. I arrived at Harvard to be paid to do anything I wanted, if you can believe it. I lived at the Science Center because I missed science terribly, and I attended lectures by Stephen Jay Gould and E. O. Wilson.

Somebody suggested that I sit in on [chemist] George Whitesides’s class because he was a terrific lecturer. I was blown away by how visual he was in his lectures, so I walked up after class and said, “I would really like to take a look at what you do.” I wound up in his lab meeting his graduate students and postdocs. They had just gotten a paper accepted to Science. I looked at their images, and they were pretty awful. So I said, “Hey, let me take a shot at this"—literally and metaphorically. And we got the cover. For the rest of the year I continued playing around in his lab. I knew this was going to be a change in my profession, that I had to go into photographing the science that I loved.

PT: Tell us about the process of writing Picturing Science and Engineering. I understand it grew out of a MOOC [massive open online course] offered through MIT.

FRANKEL: A few years ago, the MIT Office of Digital Learning asked me if I could put together a course on making science and engineering pictures. I worked with a great team of people to develop a course and make video tutorials showing how to make better pictures. The course is still on edX

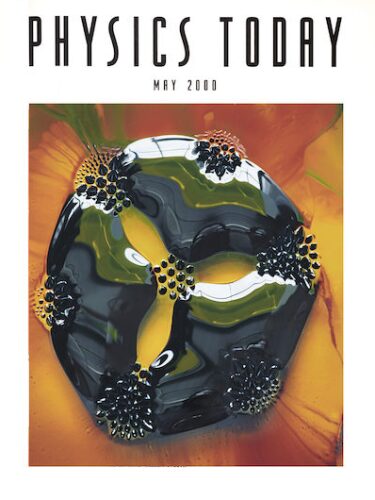

The May 2000 issue of Physics Today featured Frankel’s photo of ferrofluid. She has provided the cover images for several scientific publications.

Felice Frankel; Physics Today

When I first developed the edX course, I approached the task as if I were writing a book—by thinking about a story I wanted to tell. And so I had a valuable head start for Picturing Science and Engineering. I did add new material, specifically the chapter on image enhancement, which I think is not discussed enough in the science community.

PT: Why is it important for scientists to discuss image enhancement?

FRANKEL: There are ethical questions when you’re changing an image in a scientific paper. Scientists need to take it quite seriously when they start adjusting data. If you’ve enhanced an image, is it still accurate? How far can you go? It was very clear to me that this wasn’t discussed enough. When I went to see material from the Office of Scientific Integrity at MIT, for example, they had brochures on issues like plagiarism, but nowhere do they discuss image enhancement. So I knew I wanted to include that in the book.

PT: How did you choose which techniques and pieces of equipment to cover? I was surprised by the whole chapter on phone cameras.

FRANKEL: I am firmly convinced that the more pictures you make, the better you’ll become at being a photographer. I wanted to encourage readers to make as many pictures as they can. And I use all the pieces of equipment myself. At one time I really didn’t think anyone could ever make serious pictures with a cell phone, but I’ve definitely changed my mind. The problem is the file size, but I think eventually that’s going to change and we’ll be able to get high-DPI [digital pixels per inch] photos out of our phones.

Frankel captured this view of agate with a flatbed scanner. © Felice Frankel

PT: What common mistakes do scientists make when they try to use pictures or other visuals to communicate important aspects of their work?

FRANKEL: The challenge for researchers is that they assume we see what they want us to see. They have been working on the subject for so long, their eyes go right to the important elements in their picture. It’s difficult for them to understand that many of their images are packed with distracting pieces that don’t help readers see the point of the image.

So the first thing I tell my students to ask themselves is “What is the purpose of this photograph or graphic?” Are you showing a detail? Showing a process? Showing a comparison? If you cannot come up with a one-word explanation for what you’re trying to do, you have to go back to the drawing board because you can’t say everything in one figure. I also ask students to take their figure to a first-time viewer and ask, “What’s the first thing you see?” The third and final question is “What can I delete?” Because every single figure that I’ve seen throughout my career started out with too much information.

PT: What is your next project?

FRANKEL: There are a few in the works. I’ve been thinking about writing a children’s book to encourage kids to take pictures of the world. Another possible project is a step-by-step guide to creating images and graphics in science. But the one that’s closest to my heart is one I’ve been trying to make happen for 20 years: creating a comprehensive program on the visual representation of science and engineering. We need to teach researchers how to correctly and compellingly do what they want to do in graphics, photography, animation, and infographics. I’d also love to offer a certificate program to folks like me, people who have a science background or who love science. Students would learn to work with the tools that are now available and to develop new ones to get visual depictions right while maintaining the integrity of the science.

PT: What are you reading right now?

FRANKEL: I listen to books these days. Right now, I’m loving Michelle Obama’s book Becoming.