Astronomers seek to reduce glare from satellite swarms

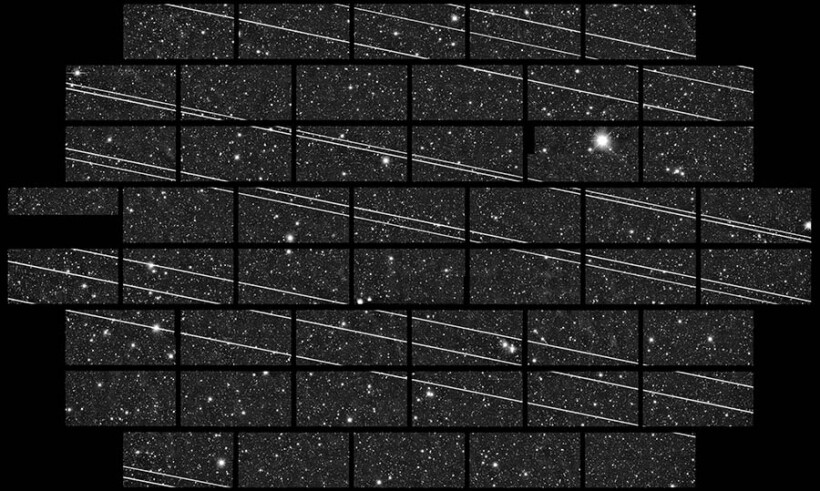

Bright trails left by SpaceX Starlink satellites are visible in a wide-field image captured by the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile.

CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/DECam DELVE Survey, CC BY 4.0

A new report

The conclusions are drawn from a virtual workshop

“The reality of this newly emerging challenge . . . is that there are no remote locations that are immune,” Phil Puxley, vice president for special projects at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, said at a press conference

“Extreme” impacts expected

Satellite constellations have been an urgent concern for the astronomy community since SpaceX in May 2019 launched its first train of small-scale communications satellites, which proved to be unexpectedly bright in the night sky. Though that first launch involved only 60 satellites, the company has outlined plans to deploy 30 000 as part of a decade-long project called Starlink to provide global broadband internet. OneWeb and Amazon’s Project Kuiper are also planning such projects, often referred to as megaconstellations. According to public filings, more than 100 000 low-Earth-orbit satellites have been proposed for launch over the next decade.

The report estimates the impacts on nine representative astronomical observation types, finding they can range from “negligible” to “extreme” depending on the science goals of the observations and the constellation’s characteristics. For instance, satellite trails could stymie time-sensitive observations of gravitational-wave sources and other rare transient events, which are critical to the emerging specialty of multimessenger astronomy

The report closely considers the potential impacts on the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which is currently under construction in Chile and was the top priority for ground-based optical astronomy

“It’s a perfect machine, unfortunately, to run into these things,” the observatory’s chief scientist, Tony Tyson, said at the press conference.

Continued collaboration sought with constellation operators

Workshop cochair Connie Walker of NOIRLab stressed that “no combination of mitigations will eliminate the impact of satellite constellations on optical astronomy.” The report recognizes the option of not launching constellations at all, but Walker acknowledged that this route is “not viable for industry.” Accordingly, the report focuses more on actions that astronomers and satellite operators can take both independently and in concert to avoid the most serious forms of interference.

One key recommendation is that operators deploy constellations below an altitude of 600 kilometers to reduce the number of visible satellites. Simulations show that constellations orbiting below that threshold fall entirely into Earth’s shadow for much of the night, whereas some satellites in higher constellations remain visible all night long in the summer.

Both Starlink and Kuiper have sufficiently low orbits, but OneWeb’s constellation has a planned altitude of 1200 kilometers, which would leave hundreds of satellites illuminated. OneWeb paused its deployment after filing for bankruptcy in March but soon after filed a proposal to increase its constellation to 48 000 satellites. In July the company announced

The reflectivity of the satellites is also a critical factor, as very bright satellites can oversaturate detector pixels, making instruments difficult to calibrate and leaving uncorrectable artifacts in the data. Drawing on measurements and simulations, the report recommends darkening satellites to an apparent magnitude of at least +7, just dim enough to be invisible to the naked eye. (The scale is logarithmic, with lower numbers indicating greater brightness.) It also suggests that operators position the satellites to avoid reflecting sunlight toward the sites of major observatories.

Although the brightness of the Starlink satellites already in orbit varies considerably, the report states the average apparent magnitude of 281 satellites measured in late May and early June was +5.5. SpaceX has begun testing strategies for reducing its satellites’ brightness. In January it launched an experimental satellite called DarkSat

Even with such measures in place, satellite trails will still show up in astronomical data, so the report recommends that researchers develop software applications that can mask or remove them from images. Detailed simulations will also be necessary to understand systematic uncertainties and residual signal-to-noise effects caused by masked satellite trails. The report further suggests that satellite operators provide detailed orbital position information for their constellations so that researchers can account for their presence in planned observations.

Editor’s note: This article is adapted from a 1 September