As its renaissance recedes, US nuclear industry looks abroad

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.1782

A combination of prohibitively large capital costs, aftershocks from last year’s catastrophe at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, and the recently discovered wealth of cheap natural gas has added up to a bleak outlook for the US nuclear energy sector. With that in mind, three recent reports from Washington, DC, think tanks have urged that the federal government help shore up the US industry on national security grounds. They warn that loss of the longtime US leadership position will do great harm to the international effort to stave off nuclear proliferation.

“We are going to have no ability to deal with the proliferation issues that are attendant to the development of nuclear power if we are not a participant in the business,” former national security adviser Brent Scowcroft warned at an 18 September conference on nuclear energy in Washington, DC. He noted that 60 or more nations have shown interest in acquiring nuclear energy. “Having US [nuclear] exports successfully deployed in other countries increases not just our safety footprint, but our nonproliferation blueprint,” agreed Marvin Fertel, president of the Nuclear Energy Institute, the US nuclear industry’s trade association.

Only a few years ago, as pressure grew for action to curtail carbon emissions from fossil-fuel generation, the future of the US nuclear industry appeared bright. (See Physics Today, February 2006, page 19

Arguably the worst setback for nuclear energy’s immediate hopes is the country’s largely unforeseen rapid development of vast shale-gas reserves over the past decade. Plummeting natural-gas prices are encouraging electric utilities to replace many of their oldest and worst-polluting coal-fired plants with gas generation; as many as 57 GW of the more than 300 GW of US coal-generating capacity will shut down by 2022, Fertel said. Cheap gas also may cause some smaller, older nuclear plants to be shuttered before their operating licenses expire, he added.

“Right now the [nuclear] equation just does not work and has no reasonable prospect of working,” said Michael Wallace, a former chief operating officer at Constellation Energy and now a consultant to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Wallace has the personal experience of trying to arrange financing for construction of a 1600-MW reactor at Constellation’s plant in Calvert Cliffs, Maryland. The deal, in which government-owned Electricité de France was a partner, fell through in 2010 when Constellation decided it would not pay the 11% fee that the Department of Energy would charge for the needed $7.5 billion loan guarantee.

With 104 reactors, the US still leads the world in the number of operating units, and about 20% of its electricity is supplied by nuclear energy. After passage of the Energy Policy Act in 2005, which provided new economic incentives for nuclear power, 18 utilities applied to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) for licenses to build and operate 28 new reactors. DOE received 19 applications for loan guarantees to finance 21 reactors. Today, with electricity demand still below its 2007 level, plans for all but four reactors are on hold. Seven years after the loan guarantees were authorized by Congress, only one, for $8.7 billion, has been approved; it will allow Southern Co to add two new advanced reactors at a plant in Georgia.

If current trends continue, Wallace said, as many as 40 US reactors could be shut down by 2030. The US share of global nuclear generation is expected to shrink, from around 25% today to 14% in 2030, and to less than 10% by midcentury, according to the CSIS report 2012 Global Forecast: Risk, Opportunity, and the Next Administration (http://csis.org/files/publication/120417_gf_wallace_williams.pdf

Help wanted

The economic headwinds provide a compelling case for government involvement to keep nuclear power afloat, the three reports stated. Since the birth of the industry in the 1950s, the US has dominated the development of global standards for nuclear plant operations, safety, maintenance, and emergency response. And NRC approval is considered to be the world’s “gold standard” for reactor designs, said Fertel. “Our technology is still the most advanced technology. Our passive safety systems are more advanced than anyone else’s,” he said. “Countries that are starting up are looking to the NRC for the regulatory framework that they want.” Fertel added that one lesson learned from the Fukushima disaster was that Japan lacked effective government regulation.

As for proliferation concerns, the US government maintains considerable control over the end users of nuclear exports. Under so-called 123 agreements, buyers of US reactors, for example, may not reprocess their spent fuel without US approval, since the US considers reprocessing a proliferation risk. “Countries that do not enforce stringent nonproliferation protocols, such as Russia, are now able and eager to export nuclear technology to countries like Iran,” according to A Strategy for the Future of Nuclear Energy, a report written by Third Way and the Idaho National Laboratory (http://www.thirdway.org/subjects/9/publications/540

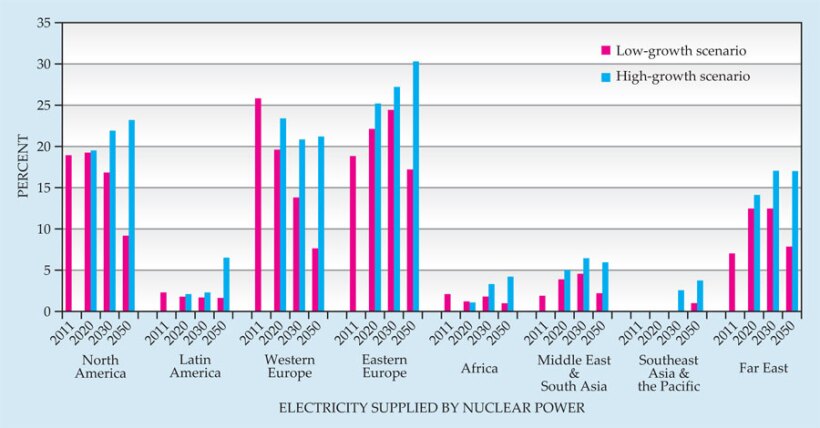

But will there be a market for US nuclear exports? Experts say yes. With notable exceptions, such as Germany’s post-Fukushima decision to phase out nuclear energy and Japan’s possible scaling back, considerable nuclear growth is still expected abroad. Hans-Holger Rogner, head of the planning and economic studies section of the International Atomic Energy Agency, says the Fukushima disaster has delayed worldwide growth projections by as much as 10 years. Still, the agency’s 2012 low-end world forecast is for growth of 25% by 2030, from 370 GW to about 456 GW. On the high end, “if everything goes nuclear’s way,” Rogner says a 50% increase is possible in the same period.

“Most developing countries continue with their movement toward a nuclear power program,” says Rogner. “Probably [since Fukushima] they now understand better what we always said: It will take time. You have to build up the necessary infrastructure—from safety culture to nuclear law to international conventions—and human resources development. All these things are a time-intensive and time-consuming process.”

According to the CSIS report, China could have 50 reactors operating by 2016, up from 14 in 2011. Russia is expected to add 10 reactors and India 8 by 2016. The US Energy Information Administration projects that both China’s and India’s consumption of nuclear power will grow annually by 10% from 2008 to 2035, while US demand will remain flat. The agency predicts that China will overtake the US in nuclear power demand by 2034.

Financing is a different issue in developing countries, where governments tend to be heavily involved in the utility sector, says Rogner. Each of the reports notes how the US nuclear industry must compete not against other companies so much as against other countries, decades of US government-funded nuclear R&D notwithstanding. “We need to be helped more by the government, by removing obstacles and helping to facilitate things, to sell US technology,” said Fertel.

Although other nations are looking at shale gas, too, the resource isn’t equally distributed worldwide. And gas does emit carbon, albeit only half as much as coal. For those reasons, says Rogner, shale gas should be viewed as a supplement rather than a substitute for nuclear or other carbon-free energy sources.

A world beater?

The US industry is pinning much of its hopes on a new nuclear product it believes it can sell to the world: small modular reactors (SMRs; see Physics Today, August 2010, page 25

Rogner says SMRs are more financially attractive and better suited for today’s slow-growth electricity demand. Many utilities don’t see sufficient demand growth to justify building a conventional reactor. Moreover, he adds, “not too many utilities have the capitalization to finance a 1600-MW reactor for $6 billion or so.” But with an SMR, additional modules can be added on as demand grows.

Cooperation with the NRC and other agencies, such as the Department of Commerce, which regulates exports, will be critical to enable the US to be first-to-market with SMRs, said Fertel. The industry’s goal is to have the first SMRs deployed by 2022.

The International Atomic Energy Agency sees a wide range in nuclear energy’s potential share of total electricity generation in the coming decades.

INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY

More about the authors

David Kramer, dkramer@aip.org