Artificial materials manipulate heat flow

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.1629

Heat flux is all around us—everywhere there’s a temperature difference. It’s intuitively easy to understand, at least at its most basic level: Heat flows from hot to cold and does so more readily through some materials than through others. But compared with the analogous flow of electric current, heat is much more difficult to control or put to good use. Better control of heat flux could help protect sensitive electronic components from temperature extremes, better harness solar thermal energy, or, more speculatively, create thermal analogues of electronic diodes and transistors.

Now Yuki Sato and his postdoc Supradeep Narayana, of the Rowland Institute at Harvard University, have used techniques from the field of metamaterials in order to manipulate heat flux.

1

Inspired by work on devices that “cloak” regions from electromagnetic waves (see PHYSICS TODAY, February 2007, page 19

They quickly realized that no ordinary substance would do the trick. A hollow cylinder of a material with thermal conductivity much higher or much lower than the background material could lessen the thermal gradient inside, but at the expense of severely distorting it outside. “We started out by going back to basics,” says Sato, “drawing up thought experiments to challenge our understanding of thermodynamics and to push the envelope a little and then trying to design physical systems to mimic them.”

What they needed, the researchers found, was a material with anisotropic thermal conductivity. To make it, they stacked many alternating thin sheets of two ordinary materials, one a good thermal conductor and the other a good thermal insulator. Perpendicular to the planes of the sheets, their thermal resistances add in series; parallel to the planes, they add in parallel. With a suitable choice of the two materials—the product of their thermal conductivities must equal the square of the background material’s conductivity—the stacked layers blend into the background material and induce almost no distortion in the surrounding thermal gradient.

By arranging the layers in concentric circles, Narayana and Sato created a thermal shield that isolates the region inside from any measurable thermal gradient at all. Arranging the layers as radial spokes did the opposite: It enhanced the thermal gradient in the region inside the cylinder, a useful task in many energy applications.

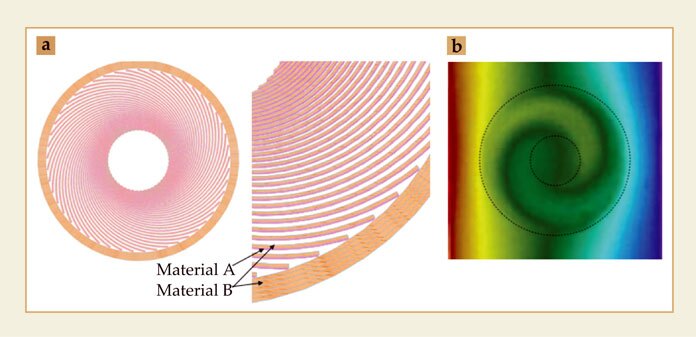

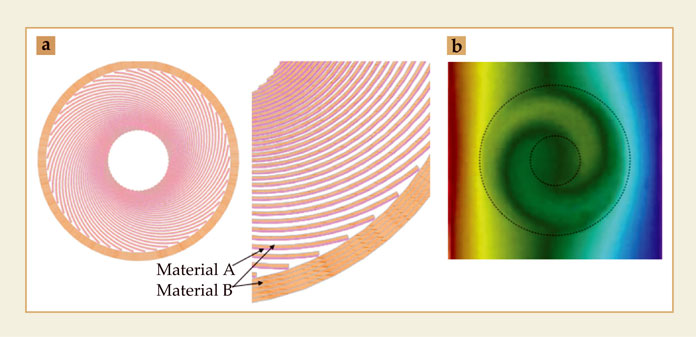

But when they arranged the layers in a spiral pattern, as shown in panel a of the figure, they achieved perhaps the most counterintuitive effect of all: local inversion of the flux direction so that heat flows from right to left inside the cylinder in response to a left-to-right flux outside. Panel b shows the temperature map as imaged with an IR camera. Heat still flows from hot to cold (as it must), but the positions of the heat source and sink inside the cylinder are reversed.

A thermal inverter (a) made from layers of copper (material A, pink) and polyurethane (material B, orange) arranged in a spiral pattern. (b) When the inverter is embedded in an agar–water block that is subject to a thermal gradient, the gradient outside the cylinder is only slightly distorted. But the gradient inside the cylinder is reversed: The cylinder’s inside edge is slightly warmer on the right than on the left. (Adapted from ref.

Narayana and Sato are working on incorporating other materials engineering techniques into their toolbox for designing their thermal materials. They’d also like to explore the potential of materials with strongly temperature-dependent thermal conductivities.

References

1. S. Narayana, Y. Sato, Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 214303 (2012).https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.214303

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org