An extraordinary gamma-ray burst lives up to its nickname

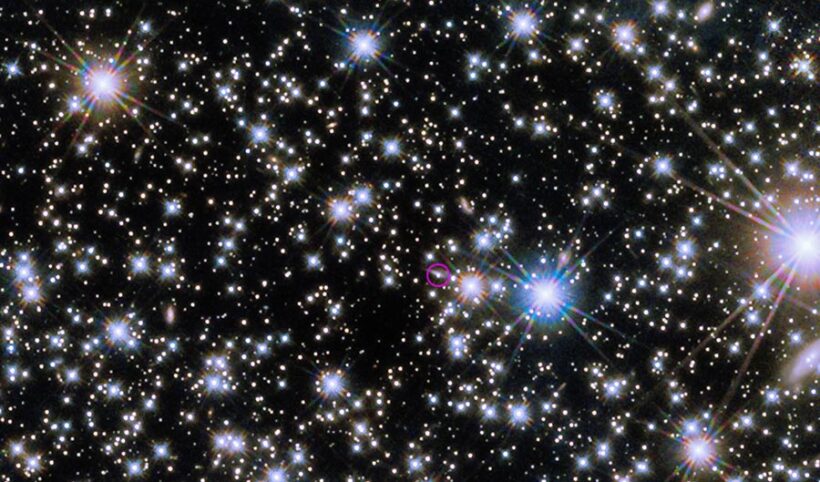

The afterglow of GRB 221009A, along with its host galaxy, is circled near the center of this late 2022 composite image from the Hubble Space Telescope.

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, A. Levan (Radboud University); image processing by Gladys Kober

Eric Burns, an astrophysicist at Louisiana State University, was on a flight to South Africa last October when a text alert appeared on his phone. The Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope had detected a burst of high-energy radiation. Around the same time, the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory picked up a flash so bright that researchers believed it was coming from within our own galaxy. Astronomers soon realized they were seeing a single event, and they rushed to hunt for the source.

What the two NASA telescopes had caught, it turned out, was an especially bright gamma-ray burst. GRBs are the universe’s most luminous transient events. The “long duration” ones, with peak emissions lasting more than two seconds, are thought to be caused by extraordinary supernova explosions. This event, deemed GRB 221009A, didn’t just have notably high energy; it was also relatively nearby, as determined by redshift. At 2 billion light-years away, the burst was well beyond the Milky Way but much closer than the average GRB, which is usually found several times as distant. The combination of energy and proximity led researchers to give GRB 221009A the nickname BOAT, or Brightest of All Time.

Burns and 29 colleagues from around the world set out to test the validity of the BOAT’s given title. “I realized everybody was calling this one the brightest of all time, but nobody had actually shown it,” Burns says. Using data collected since the first GRB detection 55 years ago, the team compared the observations of the BOAT with those of nearly all other identified GRBs. Their findings

The exceptional burst provides researchers an unparalleled opportunity to study the origins and nature of GRBs. The BOAT is “better than once in a lifetime,” says Mansi Kasliwal, an astronomer at Caltech who was not involved in the research. It’s a “once in human civilization type of event.”

A doubly rare event

Burns and his team used data from GRB monitors aboard Fermi and NASA’s Wind spacecraft to calculate two measures of brightness from the BOAT. As an indicator of the total energy released by the GRB, the researchers calculated the amount of energy detected per unit area, known as fluence, during the initial burst. Then they determined the maximum per-second fluence of the burst, known as peak flux.

The researchers compared the BOAT with the more than 10 000 GRBs identified since the US Air Force’s Vela satellites detected a burst in 1967. They found that the BOAT comfortably outdid all other observed GRBs in measured values of fluence and peak flux. Its fluence was buoyed by the fact that its period of greatest energy emission lasted 10 minutes, far exceeding the long-duration GRB average of 30 seconds. And its peak flux was more than 40 times as high as a 1983 GRB that is among the brightest ever detected.

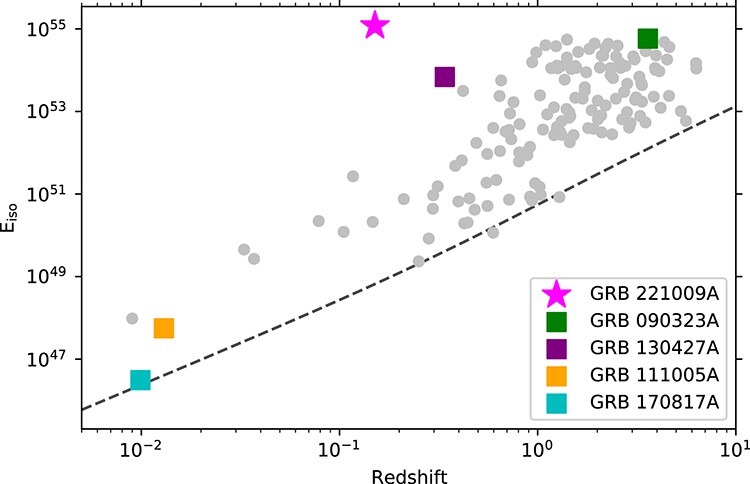

Not only is the 9 October 2022 gamma-ray burst (pink star) the most intrinsically energetic burst ever observed, but also it took place relatively nearby.

E. Burns et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 946, L31 (2023)

The BOAT was so bright that it would have been detectable even if it had occurred well beyond the distance at which any other long-duration GRB has been found. It is “intrinsically the highest energy we’ve ever seen from a gamma-ray burst,” Burns says, and among the highest in terms of intrinsic luminosity—the energy emitted per unit time.

“What was really amazing about this event is that this was both intrinsically really luminous and in our backyard,” says Kasliwal. This combination is what ultimately makes the BOAT “doubly rare,” she says.

Along with tracking 55 years of GRB data, Burns and his team created distributions showing the expected recurrence rate for a GRB with the brightness values seen for the BOAT. They calculated that a GRB with the fluence of the BOAT wouldn’t be seen again from Earth for 9700 years. The peak flux of the BOAT was even rarer, with the researchers finding that one might not occur again for as long as 15 500 years. In all, the researchers concluded we are unlikely to see an event like it for another 10 000 years.

Combining the pieces

It’s “pretty impressive that we were privy to such an energetic event,” says Brian Metzger, a Columbia University physicist who was not involved in the Burns team’s study. An influx of new research is already parsing what can be learned from the burst.

For one, some researchers have suspected GRBs could be a source of high-energy neutrinos. Yet, investigators from the IceCube Neutrino Observatory reported that their search for emissions of the elusive particle from the BOAT turned up empty

There’s also the question of what caused GRB 221009A. Exceptional GRBs like the BOAT are known to be caused by a type of supernova called a collapsar