An eruption mechanism for underwater volcanoes

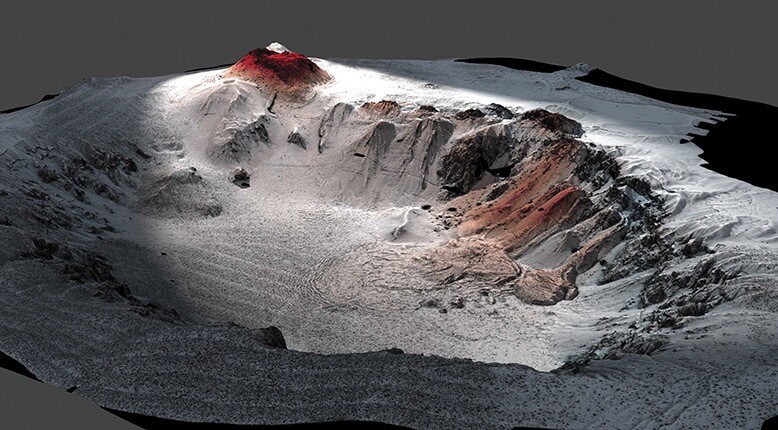

High-resolution seafloor topographical image of the Havre caldera taken by an autonomous underwater vehicle. Newly erupted lava from the 2012 eruption is in red. The caldera is nearly 5 km across.

Rebecca Carey, University of Tasmania, and Adam Soule, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The 2012 eruption of Havre volcano off New Zealand’s coast was the largest underwater eruption ever recorded. It produced a 1 km3 raft of pumice that floated to the ocean’s surface and 0.1 km3 of giant blocks of seemingly similar pumice, shown in the image below, that sank to the ocean’s floor. Now geophysicist Michael Manga of the University of California, Berkeley, and his colleagues have explained how a single underwater eruption can produce both floating and sinking material.

Submarine volcanoes account for 70% of Earth’s volcanic activity, but their magma flow differs from that of their land-based counterparts. In an effusive on-land eruption, magma flows slowly from the vent and eventually solidifies into denser rock. In an explosive eruption, dissolved volatiles form bubbles in the magma as it approaches the surface. During ascent, the bubbles burst and the brittle magma fragments into pieces, or clasts, that cool into pumice. But underwater, hydrostatic pressure from the ocean usually prevents magma from degassing and fragmenting. The pumice expelled from the Havre volcano was therefore a mystery. To solve it, Manga and colleagues proposed that the magma erupted effusively and fragmented only after leaving the vent. It retained enough dissolved water to be runny, with too low a strain rate for brittle fragmentation. But it contained enough gas to be buoyant relative to seawater. Cold water then quenched the hot lava’s surface, producing a network of cracks that led to fragmentation. The clasts’ fate depended on whether they took in water.

To test their theory, the researchers measured the amount of liquid water and trapped gas in pumice samples from both the seafloor around Havre and the raft of rock above that they collected during an expedition to the site. They heated dry samples to 700 oC and placed them in a dish of cold water. X-ray computed microtomography revealed the volume of glass, water, and gas in each sample. The researchers found that the heated raft pumice retained enough gas to remain buoyant, while the seafloor fragments became waterlogged. They also determined that raft samples contained isolated holes, while seafloor pumice had a fully connected network of pores. The team concluded that clasts from the eruption floated toward the surface, where air entered the pore space: A clast with isolated pores would retain air and stay afloat; a connected network would fill with water and sink. (M. Manga et al., Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 489, 49, 2018