Airport checkpoint technologies take off

DOI: 10.1063/1.3463622

In the wake of the failed attempt in December 2009 to bring down a Northwest Airlines flight with powder explosives, the US Transportation Security Administration (TSA) has accelerated the revamp of its airport screening technologies. Armed with funds from the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, TSA is spending $50 million on trace-explosives detection systems, $22 million on liquid-explosives scanners (see story on

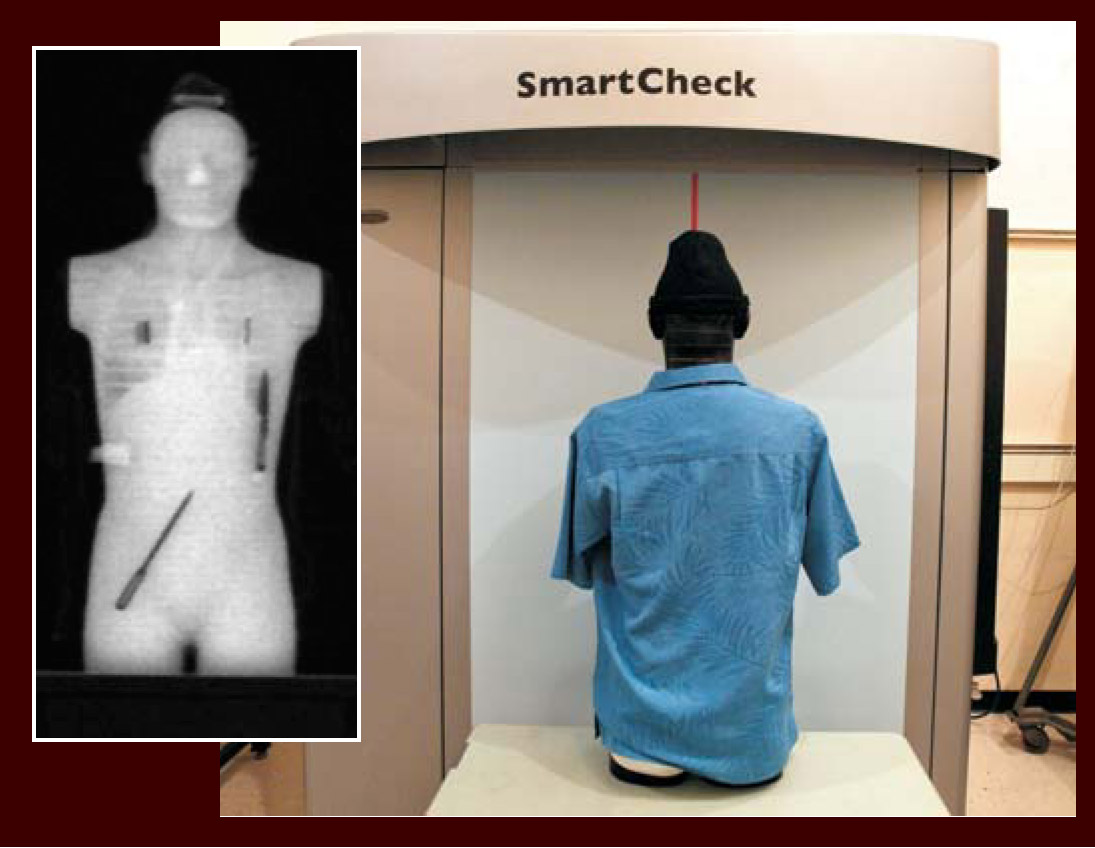

So far, TSA has installed more than 95 full-body scanners, at about $160 000 each, in 31 US airports; it plans to deploy up to 450 by the end of the year and 500 more next year. Among the primary suppliers are California-based Rapiscan Systems, whose system generates images from backscattered x-ray radiation, and New York–based L-3 Communications, whose scanners generate images from reflected or scattered millimeter waves. Both systems take less than 10 seconds to screen one person, not including the time it takes a TSA agent to analyze the image.

The agency has been evaluating both technologies in airports since 2007. And their use and development date back even further, says Michael Gray, director of radiologic compliance and safety at Rapiscan. “Our scanners have been used in courthouses, prisons, and even in battlefield zones for many years.”

Millimeter-wave systems come with a tradeoff between penetration and spatial resolution, says Erich Grossman, who has developed superconducting detectors for millimeter-wave scanners at NIST in Boulder, Colorado. “As you increase frequency, clothing becomes progressively more opaque, but spatial resolution becomes better.” Another challenge is that the reflected waves often return depolarized or otherwise distorted. Terahertz (submillimeter) technology is in its early stages of addressing those issues, “just like radar technology had to,” says Edwin Heilweil, who works on terahertz imaging and spectroscopy systems at NIST headquarters in Gaithersburg, Maryland. The initial goal was that “we’d be able to see and analyze things inside packaged goods, or envelopes, as in the case of the anthrax scare in 2002.”

Virtual pat-down

To address critics’ privacy concerns, manufacturers of x-ray and millimeter-wave scanners are incorporating technologies that blur the scanned person’s face or present an outline. L-3’s new millimeter-wave scanner uses software to automatically identify potential threats and alerts a human screener only if a threat is spotted; the scanner was recently installed at Amsterdam’s Schiphol international airport, where the December suspect boarded. Arguing in favor of body scans, Gray says, “I travel extensively, and I’m always amazed at the lack of consistency of pat-downs.”

Other critics worry that the x-ray backscatter machines could cause cancer, although they are limited to a radiation dose of 0.25 microsieverts per screening. Mahesh Mahadevappa, chief physicist at the Johns Hopkins University Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, says, “A person would have to go through [an x-ray backscatter scanner] 1000 to 2500 times in a year to equal the dosage of one chest x ray.” NIST scientist Bert Coursey, who develops performance and safety standards for the Department of Homeland Security, says that the x-ray backscatter systems meet national health and safety standards drafted by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and the Health Physics Society and that DHS has contributed to a similar set of standards to be released by the International Electrotechnical Commission next month.

Manufacturers don’t always report dosage values that are comparable, says radiation physicist Lawrence Hudson, who is developing performance tests for x-ray backscatter systems at NIST headquarters. “When trying to measure very small exposure from rapidly moving narrow x-ray beams, one must carefully account for various factors,” he says. To evaluate a scanner’s image quality, NIST uses ANSI standards to develop test kits that contain materials with differing physical and chemical properties to measure various image-quality metrics, such as resolution and materials discrimination. Using specific threat objects to test systems, as TSA does, is important, says Hudson, “but quantitative standard artifact testing is more scientific.”

Multimodal screening

In another section of NIST’s Gaithersburg campus, similar quantitative standard artifact testing is being conducted with spectrometers and gas and ion chromatographs that detect trace explosives. After TSA agents swipe a passenger’s hands, shoes, or luggage, they place the swipe material into a machine that desorbs the particles by heating, then aerodynamically transfers them to an analysis chamber, says NIST research chemist Greg Gillen. “We [develop] the best practices for collecting samples,” says Gillen, such as applying the appropriate force when swiping. Gillen’s labs are also studying the thermal, electrostatic, and aerodynamic effects of particle desorption.

Future airport screening technologies will be multimodal, says James Tuttle, explosives division director at DHS. “Advanced and automated imaging systems integrated with a trace-explosives detection portal are an example of the kind of technology that might be in the airports five to eight years from now.”

Backscattered x-ray radiation off a clothed phantom made of real human bones reveals in the scanned image a razor blade (right chest), a ceramic knife (left abdomen), powder explosives (right abdomen), and other potentially dangerous items. NIST is evaluating this full-body scanner, manufactured by American Science and Engineering, and others for use at airport security checkpoints.

NIST