AGU Chapman Conference 2012: Of ash and airplanes

DOI: 10.1063/PT.4.0419

The focus of the first session at the AGU Chapman Conference on Volcanism and the Atmosphere

The other focus was on the importance of real-time monitoring of volcanic ash in light of the unpronounceable volcano’s 2010 activity and other eruptions. Providing better input and initialization parameters for models, predicting plume movement, and combining ground-based and satellite data were the themes of the day.

During Eyjafjallajökull’s eruption in 2010, the ash cloud spread over much of Europe and wreaked havoc on air travel. Aircraft hazards from ash particles include abrasion of windscreens and internal engine parts, carbon deposition on injectors, blade cooling problems, clogging of bleed-air passages, and heat damage to the electronics. Knowing where the ash travels, how concentrated it is, and the associated risks is critical for avoiding a repeat airline crisis.

Forecasting services

“The key to improving models is being able to rapidly assess ash emissions and variations in time,” says Gerhard Wotawa of the Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics in Vienna. Characterizing the properties of ash and gas near the source of the volcano is critical for groups such as the European Space Agency–funded Volcanic Ash Strategic Initiative Team, or VAST, and the UK network known as VANAHEIM.

Wotawa works with VAST to calculate the sensitivity between the volcanic source and an area of interest, such as an airport: “You can use our model to check the concentration and height” of the plume, says Wotawa. One method is to check at what height the model matches a satellite measurement of where a plume is traveling, then backtrack to get ash concentrations. The final product will help the Volcanic Ash Advisory Centers (VAACs) to rapidly provide values for concentrations in given locations; it should be operational in 2014.

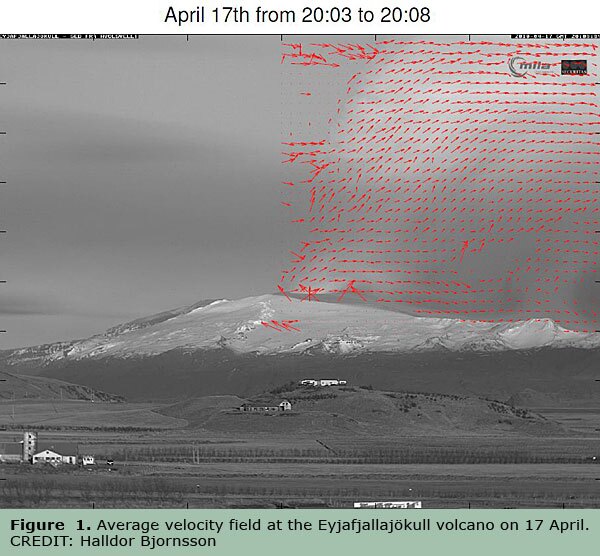

The model will be useful to the Icelandic Meteorological Office, whose job is to provide information on the height and strength of a plume at various heights. Meteorologist Halldor Bjornsson uses a cloud-tracking method; he boxes a notable feature in the first image in a time series of the Eyjafjallajökull ash cloud and follows that feature’s position in subsequent images to estimate the plume’s velocity. An average of those velocities gives a velocity field image (as shown in figure 1). Bjornsson explains that “the plume strength [discharge rate] should increase at first and then slow down. But when you increase the strength of a volcano, there are discrepancies.” Part of his goal is to figure out how to alter weather models to make them more applicable to ash clouds.

The UK Met Office operates the VAAC in London and produces ash forecasts from satellite observations, pilot reports, and models. From satellite data, meteorologists retrieve not only ash but also volcanic gas sulfur dioxide contents, and they estimate cloud heights by running dispersion models to evaluate which initial height conditions best reconstruct the satellite observations and initialize other models.

What about volcanic SO2?

Although there is a strong spatial correlation between ash particles and SO2 plumes, there are plenty of areas where ash is measured but SO2 is not. Members of VANAHEIM are investigating whether measuring SO2 can be used as a proxy for ash. “It’s much easier to track SO2 because it has a much lower background level,” explains Fred Prata of the Norwegian Institute for Air Research. “A big release of SO2 shows up like a light bulb!” Ash is much more difficult to detect because there are already ash-like particles in the atmosphere.

But using SO2 as a proxy for ash is questionable: Those two volcanic products have hugely different densities, so their travel paths in the atmosphere won’t always be the same. Pierre Coheur of Belgium’s Université libre de Bruxelles and colleagues at the Support to Aviation Control Service (SACS) are investigating whether SO2 measurements could be useful for ash modeling. In the past six years, SACS has expanded its monitoring system from its original three UV-visible satellite sounders to a multisensor SO2 alert system that provides better global coverage and confidence.

Ashes to ashes

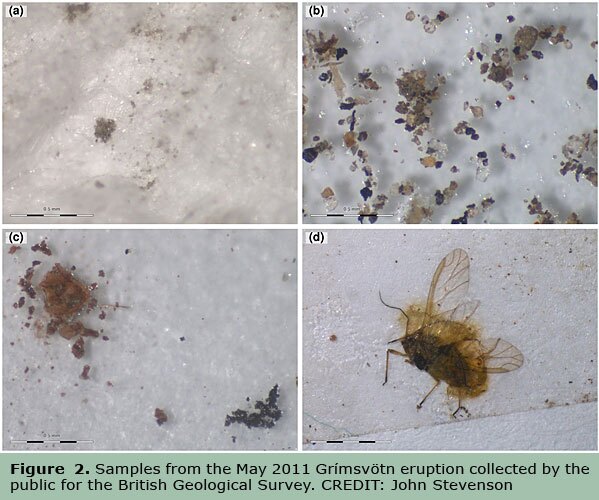

Better characterization of the ash itself is a key parameter for reducing forecast error. After the eruption of Grímsvötn in Iceland in May 2011, the British Geological Survey appealed to the public to help it determine ash distribution. Volunteers across the UK turned in 130 samples (see figure 2) of mostly tephra grains. From the samples, John Stevenson of the University of Edinburgh found that the particles had a modal diameter of 25 μm, with a maximum of 80 μm; the particles, from the lower 4 km of the plume, were spread out across the entire length of the UK.

At the same time, instrumental data from around the UK showed that concentrations of airborne particles with a diameter of less than 10 μm—the size that gets stuck in human lungs—coincided with the Grímsvötn eruption. “There’s a spike at 80 μg/m3, but the [European Union] limit for health is 50,” says Stevenson, adding that although the 10-μm ash traveled far, its concentration is low enough that it doesn’t have a big health impact. Still, he says, it’s important to know that “big grains from small plumes can still travel far.”

The refractive index of those particles is important in any climate forcing model, but current models use “only one refractive index to represent all volcanoes,” according to Adriana Rocha Lima of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. She gathered ash from the ground in Iceland, separated it with a 45-μm sieve, and re-suspended it in an air chamber to measure the absorption spectrum from which she can calculate the refractive index for a specific eruption.

Researchers from around the world are developing a range of ash forecasting and modeling techniques and methods that are diverse, are innovative, and can only benefit from further collaborations.