Academic research, DOE facilities are buoyed by recovery act

DOI: 10.1063/1.3293404

Way up in Minnesota, at the northernmost point that can be reached by road, construction is well along on the building that will house the 15 000-ton NuMI Off-Axis Electron Neutrino Appearance (NOνA) detector. One of dozens of basic research projects that are being funded by the Department of Energy (DOE) with American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funds, NOνA will tap a beam of neutrinos originating 810 km away at Fermilab outside Chicago to search for evidence of muon-to electron-neutrino oscillations.

Marvin Marshak, the University of Minnesota physicist who is NOνA’s director, says the project was so “shovel ready” after years of delays—DOE had given it the green light for construction in 2000—that it was one of the first to get under way after ARRA’s enactment last spring. With local contractors hungry for work in the recession, bids came in well under budget, and Marshak says DOE will be getting back $9.6 million of NOνA’s $30 million share of stimulus money. Even so, NOνA recently became the first DOE ARRA project to be audited by the agency’s inspector general.

Emily Carter, professor of engineering and computational mathematics at Princeton University, praises ARRA for ending “with one fell swoop” more than two decades of flat federal budgets for basic physical sciences research. She and her students no longer feel “demoralized” by all the good research topics in physics and engineering that have gone unfunded during the 25 years she’s been working in the fields, she says. But Carter, who has grants from both NSF and DOE for research aimed at developing lightweight alloys for fuel-efficient vehicles and for materials to improve the production of biofuels, says the US has lost a lot of ground to foreign competitors since the heady days of renewable energy research in the post-oil-shock 1970s. She is also codirector of a DOE-sponsored energy frontier center at Princeton, and she notes that in recent years nearly all the citations she sees in the literature on solar energy have come from Japan and Germany. The US, which once led the world, now contributes little to the field.

The money from ARRA has flooded the coffers of federal agencies with billions for basic research (see Physics Today, April 2009, page 22

Jin Kang, an electrical engineer at the Johns Hopkins University, received a $450 000 grant from NIH to develop a tool that uses optical coherence tomography to produce high-resolution images of brain tissue, which may enable noninvasive “virtual biopsies” of the tissue. The grant will fund testing on animals and cadavers. Johns Hopkins, which consistently tops the annual scorecards of academic institutions that win the most federal research grants, has been awarded more than 300 ARRA-funded grants totaling nearly $150 million.

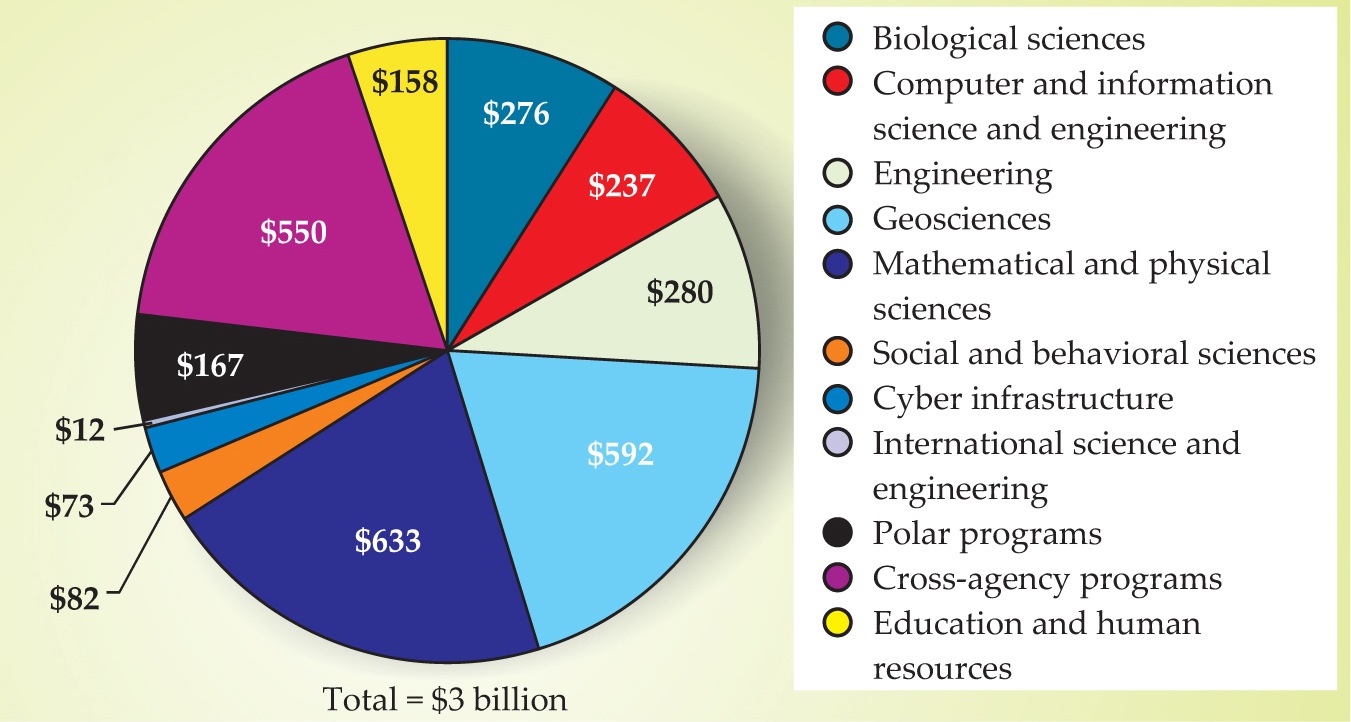

NSF focus on research grants

Of the $3 billion in stimulus money it received, NSF has committed $2 billion to support 4600 competitively selected individual and group research grants. The infusion of the stimulus cash propelled NSF’s overall applicant success rate to 32% in fiscal year 2009, a level not seen since 2000, and up from 25% in 2008. In deciding what types of research to support with ARRA funds, director Arden Bement says NSF favored proposals that were high-risk but potentially high-return research, those from new investigators, and research in the fields of clean energy and climate change, which are Obama administration priorities. All ARRA-funded NSF grants were selected from the backlog of submitted proposals that had been reviewed and highly ranked.

Another $400 million of NSF’s ARRA money was divided evenly between grants to help universities acquire major research instrumentation and grants for refurbishing academic research facilities. The remaining funds were distributed among NSF’s major research projects, including the procurement of a new ship for research in and around Alaska, an advanced solar telescope, ocean observatories, and science and mathematics education. Bement says the last of the ARRA funding will be fully committed by spring.

National labs benefit

The Office of Science, which administers nearly all DOE nonweapons basic research, took a different tack. It used most of its $1.6 billion from ARRA to make long-needed upgrades to aging facilities and equipment in its national laboratories; to accelerate the construction of a number of scientific user facilities, including NOνA; and to upgrade existing user facilities. The $912 million National Synchrotron Light Source-II at Brookhaven National Laboratory, for example, is getting $150 million in ARRA funds. The lab says the extra money will move up occupancy of office buildings at the new synchrotron by a full year, to FY 2012. The Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility at Jefferson Lab will get an additional $65 million in recovery funds. Fermilab will receive more than $100 million, including $52.7 million for superconducting RF technology and $25 million for needed infrastructure maintenance and improvements.

Some $277 million in DOE stimulus money went to establish 16 energy frontier research centers, each located at and managed by a university. Those EFRCs enjoy privileged status due to the ARRA requirement that all stimulus money be obligated by the end of this year. That legislative quirk virtually guarantees that the centers will be funded for their intended five-year lifetime. The 30 other EFRCs were established from regular appropriations, and their continuance will be subject to an annual nod from Congress. The Office of Science also used $85 million to initiate a grants program for early career scientists and $12.5 million to start a new graduate fellowship program in science, mathematics, and engineering.

Another $400 million of the stimulus went to the basic, high-risk research projects administered by DOE’s new Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy. On 7 December, Secretary of Energy Steven Chu announced a second ARPA–E solicitation of proposals to create biological approaches for converting carbon dioxide to liquid transportation fuels, to produce innovative materials and processes for advanced carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, and to develop batteries for electrical energy storage in transportation. A total of $100 million is to be awarded. Another $151 million was awarded last November (see Physics Today, December 2009, page 26

Basic research represents only a small fraction of the $32.7 billion that DOE received in stimulus money. The bulk has gone to the agency’s applied energy programs. Energy efficiency and renewable energy programs alone are receiving $16.7 billion, much of that going to pass-through grants to state authorities and to the support of green energy pilot-scale and demonstration projects. Some $4.5 billion is devoted to upgrading the nation’s power transmission and distribution grid, and $3.4 billion is going into developing clean coal and CCS technologies. On 4 December Chu announced the award of $977 million in ARRA funding for three CCS demonstration projects valued at $2.2 billion, with the balance coming from industry consortia. On the same day, DOE and the Department of Agriculture awarded $564 million in stimulus funds to accelerate the construction and operation of 19 pilot, demonstration, and commercial-scale facilities to produce biofuels. The grants are to be matched with $700 million in industry funds.

But how many jobs?

One of the measures of success for ARRA is supposed to be the number of jobs it has created or saved. Representative Rush Holt (D-NJ), one of three physicists in the House, says, “That’s what ordinary people think that the stimulus was about, and I don’t want anyone to lose the fact that the reason we were able to get this boost for science was jobs.”

But if lawmakers are hoping for precision in counting the number of jobs created, research projects at academic institutions may be the wrong place to look. Summaries of 50 ARRA-funded academic research projects prepared by an ad hoc coalition of universities calling itself Science Works for Us state bluntly that the NOνA project “has created 235 jobs.” But Marshak counts only 60 to 80 workers at the detector’s remote construction site, as does Fermilab’s website. The bulk of the $275 million in NOνA funding will pay for building the detector, a task that is spread among a number of collaborating universities.

The $19 million, five-year ARRA grant MIT received from DOE for the establishment of an EFRC will support 38 graduate students and postdocs and 16 faculty and private investigators at three institutions. Marc Baldo, the principal investigator, says the grant will be the sole source of support for the graduate students and postdocs, but it will pay for only a portion of the salaries of the faculty who are involved. And a $10 million NSF grant to UCLA for developing high-performance, energy-efficient computers tailored to health care and other specific applications counts summer jobs for 6 to 8 undergraduate students, 15 graduate students, and 3 or 4 lab staffers.

Many project summaries list “not applicable” for employment, including a $4.3 million NSF grant to the University of Arizona for an interdisciplinary “critical zone observatory” to explore the function and co-evolution of vegetation, soils, and landforms. Spying the omission, UA president Robert Shelton, emceeing a Capitol Hill press conference by the university ad hoc group, announced that the project, which will bring the Biosphere project back to life, will employ 45 graduate students, 11 full-time faculty, and 8 staff members.

Fears of falling

Even as recipients celebrate their good fortune from ARRA, anxiety is building that the research bonanza will evaporate as suddenly as it appeared, leaving postdocs and graduate students, and perhaps principal investigators, out of work at grant-renewal time.

“Falling off a cliff is not what we had in mind,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) said at the Science Works for Us debut. “We are very aware that we have to sustain the effort or increase it,” she said, adding, “Nobody is more aware of this than the president.” Pelosi was one of a half-dozen lawmakers and a handful of academic and industry leaders who led the push to include science and technology in last year’s $787 billion stimulus legislation. House Science and Technology Committee chairman Bart Gordon (D-TN) acknowledged that ARRA is “an anomaly,” but he says a seven-year doubling of the basic research budgets of NSF, DOE, and NIST called for in 2007 legislation he coauthored should prevent a post-stimulus plunge in funding. That outcome assumes, of course, that the necessary appropriations will be forthcoming, and that is hardly a certainty in the current fiscal climate.

Bement also downplays the idea of a sudden drop. “It’s $2.5 billion spread out over three years, and it’s not as much as it seems,” he says, noting that the ARRA-funded grants vary in duration from two to five years. On top of the anticipated annual increases to NSF’s budget, the agency has options it can use to minimize the impacts of declining funding, he says. For example, it has used only the standard grant template, which provides all the funding up front, for all ARRA-backed grants. Should the agency see a shortage of renewal funding looming in the years ahead, it can increase the number of continuing grants, which provide only a year’s worth of funding at a time. “We don’t see it as a major issue, but everybody tries to make it into a major issue,” Bement notes.

Robert Berdahl, president of the Association of American Universities, is less certain. Most AAU members are aware of the problem, he says, and he predicts that “a strenuous effort will be made to ensure that there will be a soft landing.”

DOE Recovery Act funding (billions of dollars)

NSF Recovery Act funding (millions of dollars)

Stimulating business. A gas station in Ash River, Minnesota, hopes to benefit from the nearby construction of the NuMI Off-Axis Electron Neutrino Appearance (NOνA) project. The facility, which will house a 15 000-ton detector, received $30 million in funding from last year’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

FERMILAB

More about the authors

David Kramer, dkramer@aip.org